You probably would not expect to find the ubiquitous “@” symbol in the same category as the Olivetti portable typewriter, the Saarinen tulip chair, or the Pininfarina Cisitalia 202 GT car. But on Saturday at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator, Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, persuasively argued for its inclusion in MoMA’s famed design collection alongside the items described above.

Within the very small world of museum architecture and design curators the AIC’s symposium, “Modern Construction: Creating Architecture and Design Collection” assembled a blue-chip group to discuss acquisition methodologies, philosophies, and approaches.

In addition to Antonelli, speakers included Ingeborg de Roode, Curator of Industrial Design, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Frederic Migayrou, Deputy Director, Musee National d’Art Moderne, Centre de Creation Industrielle, Centre Georges Pompidou; and Mirko Zardini, Director, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal. AIC’s Joseph Rosa, John H. Bryan Curatorial Chair of Architecture and Design, and Zoe Ryan, its Neville Bryan Curator of Design, completed the roster. Each offered a history and overview of his or her collection, collecting principles and acquisition strategies.

Any discussion of architecture in the museum arena has to start from the central idea that a museum can’t really “collect” architecture. As Rosa explained in his introductory remarks, museum architecture departments have traditionally acquired drawings, models, photographs and fragments relating to buildings. But that’s changing.

Over the course of his career, Migayrou has built two large architecture collections, practically from scratch: first for the FRAC Orleans, and later for the Pompidou, and seems to have had a swell time doing so. He breathlessly ripped through scores of images of items he had acquired at both institutions, which validated his belief in niche collecting. By originally focusing on unbuilt projects of the post WWII era, he said he was able to obtain a lot of material “that MoMA didn’t want,” including such gems as le Corbusier’s original collage limning the familiar Modulor graphic and the two most iconic illustrations from Koolhaas’ Delirious New York.

Beyond acquiring items in traditional formats, curators of contemporary work are grappling with issues related to digitization. In the architecture and design areas, more so than with “fine art,” it’s probably a more significant concern, because so much of the production increasingly exists in digital format.

For CCA, this has meant making much of its traditional holdings–drawings, plans, correspondence and other ephemera–available online. Zardini said it’s an important new kind of presence, a different framework for institutions, and one that brings its own set of issues: when you select which items to make digitally available, you’re editing, making a collection within your collection.

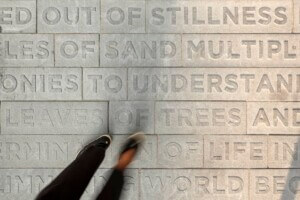

Antonelli also stressed the importance of embracing new media and formats. “Digital capabilities could free curators from the constraints of physical collecting,” she predicted. But it’s not without its challenges. In one instance, she wanted to acquire an early iteration of an e-mail graphic interface, but wondered what, precisely, to acquire. The original (probably broken-down) computer where the program was created? The actual programming code? A new machine with the old graphic interface? Video of designers revising the code for the new machine? All of the above? “Everything,” she said, “goes into the big minestrone of progress.”

Unlike architecture, design collection is generally a lot more straightforward, since many design objects are small and portable, and available to purchase outside of the high end auction houses. This has helped Ryan acquire an impressive group of objects by contemporary designers, although, having just started to build AIC’s collection over the last three years, she said, “our work has just begun.”

Her comment touched on one subject area that went more or less unexplored: what it all costs. This was an odd omission in a symposium about acquiring things. Although Migayrou revealed in his presentation that he had gotten several of his holdings “at a good price,” it was just about the only time anybody addressed the issue of money. This attendee would have enjoyed hearing the curators talk about how private collectors are competing with museums for the best items, and how the general economic malaise has affected acquisition funding–thorny problems for everyone in the museum community.