James Turrell: A Retrospective

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

5905 Wilshire Boulevard

Los Angeles, California

Through April 6, 2014

James Turrell: The Light Inside

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1001 Bissonnet

Houston, Texas

Through September 22

James Turrell

The Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue

New York

Through September 25

“We advance toward the light, only to see it disintegrate into its ephemeral nature.”

James Turrell

James Turrell works with perception—and misperception. He has been sued by someone who leaned on a “wall,” according to the deposition—but collapsed as there was nothing solid there. Another plaintiff tried to walk through a misty space, but rammed into a solid wall. Others of us relish in being a player in the subtle yet dynamic transformations that occur as our eyes adjust and environments seem to shift, defining and redefining space. With three exhibitions on view now across the country—at the Guggenheim in New York, LACMA in Los Angeles, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston—now is a rare opportunity to experience Turrell’s work.

Turrell’s medium is light: colored light and white light; artificial light and natural light; and the absence of light, darkness. He says that light making is the architecture of space, and indeed we can only perceive space when it is illuminated. When the lights go out, space seems to disappear. This plastic and material medium is the only element for Turrell. His light does not illuminate any object. Turrell has said, “Light is unlike clay, you can’t form it with hands, you can’t carve it away like wood, or chip it away like stone, or assemble it through welding. It’s almost like making the instrument first…and then…have it perform.”

In the 1960s, Turrell became fascinated with the elixir of light during an art history class at Pomona College when he was more interested in the luminosity and shape of the slide projector’s beam of light than the projected image of an artwork in the darkened classroom. (He also was frustrated that these projections made all art the same size.) His work Afrum (White), 1966-67 (displayed in all 3 venues) uses a Leitz slide projector with high-intensity tungsten light (later iterations use quartz halogen) using a template to delineate the shape—two flat white panels of light splayed in the corner of a darkened room, which look 3-D. What is this “volume? Is it a cube? A window? It’s all about ambiguity, and is dependent on where the viewer stands. It is as deceptive as a 2-D painting alluding to 3-D.

|

Twilight Epiphany, 2012.

Florian Holzherr

|

||

Afrum grew out of the Mendota Stoppages, works made in the defunct Mendota Hotel in Santa Monica, where Turrell blocked out all external light by painting the windows, and then cutting into the building—a West Coast Gordon Matta-Clark. The result was a series of controlled light performances using both daylight and urban light at night to create a carefully timed, choreographed viewing experience. His series Projection Piece Drawings, 1970–71, explore on paper the differing ways a solid white light triangle or rectangle will impact a gridded room, whether on the walls, in the corner, or bleeding onto the floor. You can see Turrell working out the mathematical principles of how to render his projections in space. After all, this comes on the heels of the moon landing, the TWA terminal, John Cage’s silent compositions as well as Turrell’s contemporary Southern California artists in the Light and Space movement.

|

Afrum (White), 1966 (left). key lime, 1994 (center). Bridget’s Bardo, 2009 (right).

Courtesy Museum Associates/LACMA; Florian Holzherr

|

||||

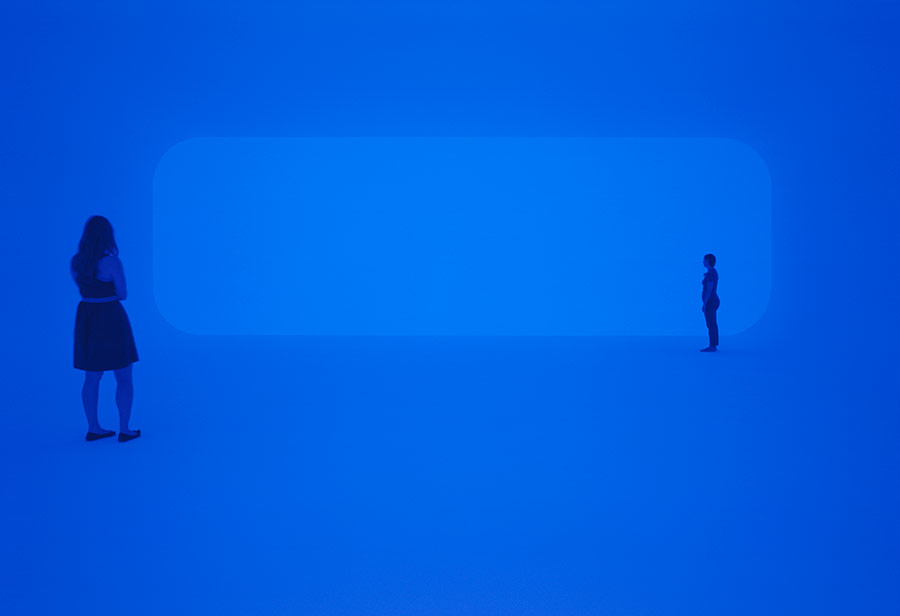

The Projection Pieces—single, controlled beams of light from the opposing corner of the room, appearing as a 3-D forms—which were also done in colors, led to slits or cuts in a wall that seem to modify the perspective on the room (Ronin, 1969, on the Guggenheim’s mezzanine), and then whole portions of a building removed in Skyspaces, such as the open-air, celestial-vaulted permanent installation at PS1. (Interestingly, PS1’s Meeting, 1986, was achieved by its own slight of hand. When the building was under renovation, then-director Alanna Heiss slipped it in as part of the architectural refurbishment, rather than as an art installation.) Experiments in light include Wedgeworks, where the precise use of projected light creates the illusion of an indented wall where none exists; Dark Spaces, closed, dark rooms without an apparent light source that takes minutes before the eyes adjust to varied interpretations of what is there; Space Division Constructs, or Apertures, which boast a horizontal block of color that appears to lead to an infinite space beyond; Ganzfeld, German for “complete field,” which gives a complete loss of depth perception through an immersive space of controlled light, coped walls, and inclined floors (in LA, after donning paper slippers, one climbs steps into the space).

The exhibition at LACMA, which runs through April 6, 2014, affords an immersion into Turrell’s work. The timed tickets restrict the number of visitors so you are often the only person in the room (same for Houston), and there are signs suggesting how long to spend in each display for eyes to adjust (Turrell says photographs do not do his works justice as they can only capture a single moment of the transforming experience.) LACMA also has a series of architectural plaster models of his magnum opus Roden Crater in Arizona, as well as the fanciful Boulle’s Boule, 1994, Transformative Space: Basilica for Santorini, 1991, and Milarepa’s Helmut, 1989.

|

Aten Reign, 2013.

David Heald

|

||

The newly created, site-specific Aten Reign, 2013, in the Guggenheim rotunda, makes one see the Frank Lloyd Wright building in new ways. The central void is filled with shifting, modulated colors that look like an oval, illuminated Josef Albers painting. Viewed only from the ground floor looking up, it takes its cues from the building itself. The Guggenheim is built around two intersecting cones; the exterior tapers at the bottom, while the interior tapers at the top. Turrell’s installation is a series of cones, like inside-out lampshades where the framework is on the outside and the fabric is on the inside, that narrow as it goes up. Five concentric double rings of LEDs shine upward, separated by fine mesh scrims, to fill the five separate conical chambers with slowly changing light that can appear flat or deep, vivid or muted. Aluminum truss scaffolding holds two layers of fabric, one white and one black, stretched taught with heat and then cooled.

In plan, the Guggenheim’s rotunda is a circle with a bite taken out, so the elliptical shape was used to maximize the impact and to make you feel like you’re in the space rather than looking at it. Although the oculus at the top emits natural light—Aten denotes the deified Egyptian sun disc—what one sees is completely controlled. Turrell develops structures to erase themselves, so that we focus on the spaces in between.

One of the unexpected byproducts of the atrium installation is how one experiences the corridors along the spiral. When you walk up or down the ramp, the perimeter walls are bare and the stretched white fabric prevents you from looking into the rotunda. The volumes, pacing, arches, and recessed lighting all become pronounced. It’s unlikely we’ll ever experience these spaces empty again.