Architecture of Independence(!): African Modernism(!). (Exclamation points mine). The title of the current exhibition at the Graham Foundation is the first hint that the show is a departure from the Graham’s usual oeuvre. More historical survey than discursive inquisition, Architecture of Independence presents an impressive catalogue of architecture from five sub-Saharan countries (rarely- or never-before-seen by Western audiences) built at the height of late-modernism, at the moment just after independence from colonial rule.

Rigorously researched and curated by Swiss architect Manuel Herz, the exhibition is the outgrowth of a book dominated by photographs by Iwan Baan and Alexia Webster. Originally presented at the Vitra Design Museum Gallery in Germany, the mounting at the Graham is the first scheduled presentation in the United States. (It will also appear at the AIA New York Center for Architecture in Feb. 2017).

According to Herz, the aim of the research is to bring the architecture into the discourse through documentation and presentation. “There is virtue in just documenting these buildings,” he said. Focusing on the multitude of public and cultural institutions built during the era, the exhibition argues that architecture was used as a nation building tool in post-colonial Africa, and that the buildings themselves act as witnesses to the complicated and often violent history and politics of the regions following independence.

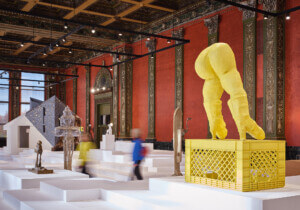

Aside from a case of archival materials that includes historical photographs, postcards, and architectural plans and sketches, the exhibition is an abbreviated representation of the book, exploded throughout the galleries. Like the book, the exhibit is organized by country: Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire are on the first floor of the Madlener House, and Ghana, Zambia, and Kenya are on the second.

This approach works best with an illustrated timeline that spans the north wall of the library, charting the political, economic, demographic, and cultural histories of each country from the time of independence to the present. Where each country’s timeline is separate in the book, the exhibit overlays them all, quickly revealing trends and discrepancies between them.

Each building is presented within a wood box with photographs and texts arranged behind glass on a wooden back.

To fit over 700 images of over 80 buildings into the frames, the photographs are snapshot-sized and the text is small, forcing an intimate proximity to the walls. While the archival-style presentation unfortunately precludes large-format prints of most of the architecture, the clustering is reminiscent of a family portrait wall, which plays nicely against the residual domesticity of the Madlener House.

To absorb the scope of the assemblage is staggering. It inspires the speculation of an entire city composed of these buildings alone: skylines full of experimental, strangely expressive, beautifully dominating, concrete and steel monoliths. It is like a hyper-Brasilia, which is itself a close relative of the work on display, both in terms of architectural style and political ambitions.

The writing accompanying each building sticks mostly to close readings and formal descriptions of the architecture. The wall text introducing each country positions the architecture as intensely optimistic projections of the hopes and dreams of newly independent nations. Like La Pyramide market building in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, or Independence Square in Accra, Ghana, massive buildings were constructed to facilitate and anticipate the rapid cultural and economic development of each nation. Now both defunct, the exhibition reveals how the architectural style and utopian rhetoric of modernism were widely adopted to bring post-colonial Africa into conversation and competition with the Western world.

Also like La Pyramide and Independence Square, most of the architecture on display was designed by European or American architects, in many cases from each country’s former colonial power.

In fact, it could be argued that the work is not the Architecture of Independence at all, but is, in every way, the architecture of colonialism; the architectural manifestation of a kind of cultural Stockholm syndrome. The authorship and intentions of the architecture presented raise important questions about the meaning of freedom, autonomy, and independence in the wake of colonialism, the effects of which continue to play out today around the world. As Audre Lorde wrote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

In the introductory essay to the book, Herz examines the complexities and problems of authorship and architectural expression in relation to the slippery meanings of the terms “independence” and “modernism” in the context of Africa. Unfortunately, that critical framework is not explicitly carried over into the exhibition.

There is also the unavoidable problem of the white gaze. The framing and narration of the exhibition and the book are situated firmly in the scholarly, white, Western view, for a Western audience, fetishizing both the architecture and the anonymous black bodies populating the images. The existence of the white gaze is not as troubling in and of itself as the fact that it goes completely unacknowledged.

From a purely disciplinary perspective, the Architecture of Independence brings attention to a canon of architectural history (for five countries) that is full of important and interesting work by European, American, and some African architects. However, it raises the questions: Who can lay claim to this work Where does it belong? In the Western discourse of modern architecture, studied alongside other known works by Denys Lasdun, Harry Weese, and Henri Chomette, or through the lens of African politics, history, and culture? While the exhibition seems to be saying both, the framing of the work seizes it solely for the Western discourse.

Many of these issues could have been addressed by simply changing the title from a statement to a question. Changing “The Architecture of Independence” to “The Architecture of Independence?” would not only shift grammar and tone to be more reflective of the complexities and idiosyncrasies presented, but it would also provide a more compelling framework for the exhibition.

Go see this show. The architecture is stunning, the research rigorous, and the images striking. Stand too close to images of iconic architecture you have probably never seen, get a crash course in the recent history of five African countries, take in the sublime photography of Iwan Baan and Alexia Webster. Do it. It’s worth it. But do so with one eye sideways, craning around the singular gaze presented to the complex questions that the exhibition raises.