On Chicago’s far South Side, tucked into a postindustrial strip of Cottage Grove Avenue that hugs the Metra tracks, Sweet Water Foundation is farming fish in a former shoe warehouse. The story of urban farming as a tool for urban development is, perhaps unfortunately, cliché at this point. Emmanuel Pratt, Sweet Water‘s cofounder and executive director, would know: He came up under Will Allen, a MacArthur “genius” grantee and founder of Growing Power. Allen practically wrote the story and developed a much-lauded and effective framework for using farming as a tool for community and economic development.

Like Growing Power, Sweet Water has operations in Chicago and Milwaukee that serve as community hubs, education centers for school groups, and employers for hundreds of youth. However, Pratt’s background in architecture and planning pushed him to take a different approach. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture from Cornell and studied under Mark Wigley as a doctoral candidate in Columbia University’s Urban Planning program. He can weave a conversation seamlessly from the biology of farming and the science of aquaponics to the architecture of space and design.

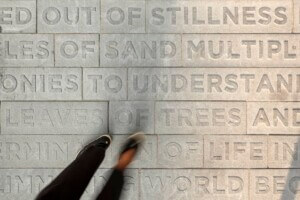

Pratt decided to form Sweet Water in 2011, because he saw farming as just one tool in the box of neighborhood revitalization. The organization’s “blight-to-life” approach uses the biological regenerative principles of nature to, in Pratt’s words, “invent new forms of building typologies.”

“It’s all about programming and reprogramming. Space is the crux, and programming is the vehicle,” said Pratt.

He describes the Aquaponics Innovation Center at the University of Wisconsin’s Stevens Point as a “tinkering shop.” Along with the 950-gallon tilapia tanks that cycle water to the vegetable beds and back, there is a full-scale wood shop run by a master carpenter, where farming infrastructure is built and participants learn design-build techniques using hand drawing, Rhino, and SketchUp. “It’s a playground. A place for imagination in a space of lost labor production, in an era of hypercapitalism,” said Pratt.

Along with the Aquaponics Innovation Center and a similar operation in Milwaukee, Sweet Water owns a single-family house that sits alone on two acres of land in Englewood. Built on the site of a former youth correctional school during the housing boom, the house went into foreclosure during the recession.

Now called the Think-Do House, Sweet Water converted the surrounding land into a working farm that feeds 200 people a week at peak growing season. The house has become a community center with workshops, classrooms, and a functioning kitchen. There is a view of the Willis Tower through the kitchen window.

“The aesthetics and conditions of the built environment play a major role in a cultural otherness that is reinforced by patterns of development in the city,” said Pratt. “Neighborhoods like Englewood have a strong housing stock from the last 100 years. Tearing down buildings is not just erasure of culture and history, it’s also a matter of material and soil waste.”

Sweet Water sees buildings as part of the ecological system of a neighborhood. “We look at the relationship between water, light, soil, plants, buildings, and culture as a closed circuit,” said Pratt.

A combination of geography, demography, and work that straddles the intersection of urban development, architecture, and community beg comparisons to flashier examples of South Side redevelopment, such as Theaster Gates’s top-down, development-as-conceptual-art project or Amanda Williams’s building-as-beacon Colored Project. However, Pratt said that Sweet Water’s bottom-up, asset-based relationship approach looks at revitalization as “not just about the economy of a neighborhood, but about the ecosystem as well.”

It may not be as sexy, but it’s working. And Sweet Water’s footprint is growing.

Directly across the alley from the Think-Do House sits the historic Raber House, a landmarked building owned by the city. Pratt told AN that Sweet Water is currently in talks with Ross Barney Architects, Latent Design, DMK Restaurants, and the Illinois Institute of Technology’s architecture department to recover the property for the neighborhood’s use.

“Building neighborhoods and the business of development are at odds,” said Pratt. “Architecture has the power to negotiate that, but there is a race for architects to catch up to their role.”