As part of its international grant initiative, Keeping it Modern, the Getty Foundation has unveiled this year’s recipients for funding. Now in its third iteration, the grant seeks to award a select group of 20th century modern architecture buildings with funds to aid their preservation. Based in California, which arguably has more than its fair share of modernist artifacts, the Foundation proclaims that as of now, “modern architectural heritage is at considerable risk.” Here is the list of nine buildings that will share just more than $1.2 million in grants.

Association de Gestion du Site Cap Moderne Villa E.1027

Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France

Built: 1929

Architect: Eileen Gray

Funds Awarded: $200,000

Designed by architect and designer Eileen Gray, this dwelling is southern France has a rather sombre history. Essentially vandalized by Corbusier who painted murals (famously doing so while nude) on the building without Gray’s permission, the murals were later used as target practice by Italian soldiers in World War II. The modernist house was then later sold onto doctor Peter Kägi who, while grappling with morphine addiction, let the house deteriorate. With rumors of it being used as an “orgy den, with Kägi picking up local boys and offering them drugs and booze,” Kägi was found murdered in the residence. Squatters and vandals later occupied the building though Corbusier’s art somehow survived. The Villa is now cared for by the Association Cap Moderne, a non-profit organization that has pledged the long-term maintenance of this Monument Historique. Funding will go toward a “scientific study of the original color scheme, climate control research, a furniture study, and a special scientific analysis of the Le Corbusier murals to inform their future restoration.”

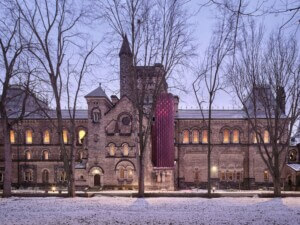

Highland Green Foundation Inc. First Presbyterian Church

Stamford, Connecticut, U.S.

Built: 1958

Architect: Wallace Harrison

Funds Awarded: $130,000

Boasting a dazzling interior (seen here in AN’s previous coverage of the building) the church is composed of prefabricated triangular panels of precast concrete. The interior is illuminated by an array of more than 20,000 shards of amber, emerald, ruby, amethyst and sapphire stained glass. This colorful method of illumination is part of Harrison’s use of dalle de verre windows—a cost-effective technique that allows the glass and concrete to work in unison. Now maintained by the Highland Green Foundation, funds will be used to “survey, document, and study the site, drawing on the input of engineering consultants and material scientists.”

Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi Casa de Vidro

São Paulo, Brazil

Built: 1952

Architect: Lina Bo Bardi

Funds Awarded: $195,000

The appropriately named Casa de Vidro (Glass House) residency was built for Bo Bardi and her husband as a private dwelling. The building demonstrates Bo Bardi’s ability to execute European modernist styles across the Atlantic and in a drastically different, tropical environment. The building is now in the hands of the Instituto Lina Bo e B.M. Bardi, an organization founded by the architect and her husband to publicize Brazilian culture and arts. According to the Getty Foundation, the grant will allow an “international team of conservation architects, landscape conservation specialists, cultural heritage experts, and civil and structural engineers to develop a conservation management plan for the property. The project will also include a 3D topographic survey of the site that allows engineers to identify potentially harmful structural deformations at the smallest scale, not perceivable to the naked eye.”

Comisión del Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación Cristo Obrero Church

Atlántida, Uruguay

Built: 1960

Architect: Eladio Dieste

Funds Awarded: $150,000

By its full name, the Cristo Obrero y Nuestra Señora de Lourdes church was the first independent commission for revered Uruguayan architect and engineer Eladio Dieste. With an undulating wave-like brick facade running lengthways on either side of the building, Dieste’s subtle articulation of light stems from a series of well-placed windows and bricks that contain colored glass. Dieste’s engineering prowess is also showcased inside through a bell tower that features perforated walls and a free-standing minimalist spiral staircase bereft of support column and a handrail. Though under the care of the local community, the Getty’s funding will facilitate the supply of a “team of national and international experts” that will carry out a “rigorous study of the church and bell tower” as part of a “comprehensive engineering study and a conservation management plan.”

ArchiAfrika Accra Children’s Library

Accra, Ghana

Built: 1966

Architects: Nickson and Borys

Funds Awarded: $140,000

After Ghana escaped the clutches of colonialism in 1957, Accra quickly became the focal point of West African Modernism, symbolizing the country’s liberation. The Children’s Library in the Ghanaian capital followed suit. With a brise soleil that acts as a simple but effective shading device, while also allowing natural ventilation of the building, Nickson and Borys’ design epitomized a radical political change for the country. Though currently in good shape under the stewardship of the Accra Metropolitan Assembly and the Ghana Library Board, the $140,000 will be used to “ensure that the building is preserved to the highest standards.” Here, a team of specialists will “collaboratively research the library complex and develop a conservation plan.”

The Writers’ Union of Armenia Sevan Writers’ Resort

Lake Sevan, Armenia

Built: 1935 & 1965

Architects: Gevorg Kochar & Mikael Mazmanyan

Funds Awarded: $130,000

Embodying the utopian ideals of the early Soviet Union, Gevorg Kochar & Mikael Mazmanyan strived to create a functional and egalitarian space derived from abstract forms. Only two years after their writers’ retreat’s construction, however, the architects fell out of favor with the Stalinist government with both being arrested and exiled to Siberia for 15 years. Returning in the early 1960s, Kochar added a new lounge and rebuilt the existing guest house. Now, the building is still used by native writers as a retreat, though the Getty has acknowledged that many modernist Soviet structures in post-USSR member states are now in danger. The grant will “support the methodical and scientific analysis of the Sevan resort” and aims to “set a precedent for valuing modernist heritage not only in Armenia, but also in other post-Soviet and post-socialist countries.”

Liverpool Roman Catholic Archdiocesan Trust Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral

Liverpool, United Kingdom

Built: 1967

Architect: Sir Frederick Gibberd

Funds Awarded: $138,000

Working alongside a group of artists, Sir Frederick Gibberd was able to design one of Liverpool’s most dominant architectural icons. A soaring lantern tower illuminates the interior through its dalle de verre stained glass, creating a sharp contrast in both tone and vibrancy with the raw white concrete of the exterior. Saddled with internal leaking and defects to the mosaic cladding of the concrete buttresses, repair work began in the 1990s. Funding from the Getty will support an ongoing study into the failure of the dalle de verre in the building’s Lantern. It will also be used to “develop and test a conservation repair methodology for the dalle de verre glazed Lantern, which is currently the cause of significant water ingress.”

Nirmala Bakubhai Foundation Gautam Sarabhai Workshop Building

Ahmedabad, India

Built: 1977

Architect: Gautam Sarabhai

Funds Awarded: $90,000

Drawing inspiration from German engineer and architect Frei Otto, the Gautam Sarabhai Workshop Building employs a steel grid frame coated by a thin-shell Ferro cement roof. This allows the interior—which stretches across 134 feet—to be free from any interfering structural columns. Thanks to the building’s light-weight structure, it was able to survive the 7.7 richter-scale earthquake in 2001. To ensure this structural performance is maintained, its owners plan on researching and creating a “comprehensive conservation plan.” This will include the development of a Building Information Model (BIM) used to monitor and track the structure’s condition, of which the Getty’s grant will support.

Kosovo’s Architecture Foundation National Library of Kosovo

Prishtina, Kosovo

Built: 1981

Architect: Andrija Mutnjakovic

Funds Awarded: $89,000

With the intention of establishing an “authentic national architectural expression,” Croatian architect, Andrija Mutnjakovic used translucent acrylic rooftop domes, in-situ cast concrete, marble floors, and white plastered walls to create a distinctly modern library. Featuring forms from the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires to reflect the areas history, materiality was also used in symbolic fashion with an aluminum lattice skin contrived by some as acknowledging the area’s two predominant religions. Though the interior was subject to damage during the Kosovo war in 1998-99, the library’s exterior remained remarkably unscathed. Now, however, the hallmarks of age such as leaks have begun to settle in. The grant from the Getty will go toward furthering conservation specialists’ understanding of the building, where “every aspect” will be studied while consulting Mutnjakovic himself.

The Getty Foundation created Keeping It Modern to complement the Getty Conservation Institute’s Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative (CMAI).