This is a story about our global urban future… It’s also a story about America’s recent urban past, in which bureaucratic, “top down” approaches to building cities… with little or no input from those who inhabit them…. Citizen Jane: Battle for the City shows that anti-democratic approaches to city planning and building are fundamentally unsustainable; a grassroots, “bottom up” approach is imperative to the social, economic, and ecological success of tomorrow’s global cities.

…Jane Jacobs… single-handedly undercuts her era’s orthodox model of city planning, exemplified by the massive Urban Renewal projects of New York’s “Master Builder,” Robert Moses.

So reads the official website for the new film, Citizen Jane: Battle for the City which opened the DOC NYC film festival on November 10. It clearly sides with Jacobs’s David rather than the Moses’s Goliath. As Paul Goldberger says, “They were famously at odds with each other. It really did become a war between opposing forces. Today, we’re still fighting these battles across the world.”

It’s a great story with large implications for our world. There is compelling archival footage and photos, and a panoply of talking heads including Mary Rowe, Michael Sorkin, Roberta Gratz, Thomas Campanella, Ed Koch, Alex Garvin, and Goldberger.

Jacobs’s rich lore is more than just a face-off with Moses (Rowe told me that in the 10 years she worked with Jacobs in Toronto, she never mentioned Robert Moses once). Jacobs saw shades of gray, used her powers of observation to spot “un-average clues” or exceptions, and was unencumbered by the theory and doctrines of the planning practice. The irony is that Jacobs’s analysis of what she saw in front of her has now been codified into a gospel to be followed slavishly (Citizen Jane is very different from the imperious Charles Foster Kane, the fictional Citizen Kane). It reminds me of Monty Python’s Life of Brian, a parody on the Messiah (Brian was born on the same day as his next-door-neighbor, Jesus Christ) who exasperatingly says to his adoring followers, “You must all think for yourselves!” to which they parrot back “WE MUST ALL THINK FOR OURSELVES!” Jacobs was nimble and inventive, a listener and watcher, and then a doer.

Jacobs’ lessons are enormous. Although I applaud the filmmaker taking a point-of-view and championing Jacobs, what concerns me is an oversimplification of the story and the facts. Understanding that films can only give broad strokes and focused arguments, we still need to be mindful that there are many factors at work. (The terms “single-handedly” and “undemocratic” in the citation above are clues.)

Moses came out of the Progressive Movement in the 1930s and created public spaces such as parks, swimming pools, playgrounds, and beaches to make life better for all. Post-War, he expanded his purview to “construction coordinator” (in all, he held twelve titles such as NYC Parks Commissioner, Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority Chairman, Head of the State Power Commission—all unelected) which gave him powers over public housing. He declared a war on slums, calling them a cancer, and his solution to the urban blight was to tear down and rebuild. With ample federal funds available, the aim was to erect an “expressway tower city,” in Jacob’s words. Goldberger cites this was a commonly-held belief at the time, but there was a price to be paid, and Jacobs was the lightening rod that pointed this out in stark relief.

The light bulb for Jacobs was East Harlem. The neighborhood contains the highest geographical concentration of low-income public housing projects in the United States, 1.54 square miles with 24 New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) developments. Also known as El Barrio or Spanish Harlem, in the un-renovated areas Jacobs observed an ecosystem, not chaos, with a vibrant underlying order, rhythms and complexity, and density as beauty. And she observed that the intentions of the planners in urban renewal developments like this were unmet (when she asked Philadelphia developers why their new structures in Society Hill weren’t working the way they were billed, she says she was told it was because people were stupid and not using the spaces in the right way.)

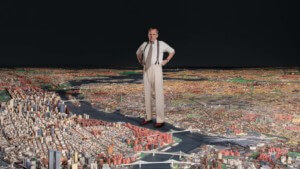

To the filmmakers, the contrast in planner rhetoric and Jacob’s common-sense observation is epitomized by the god-like, birds-eye view from the sky looking down (Moses) vs. the view from the street (Jacobs). Moses’s heartlessness and disregard are shown when he says of the people who had to be displaced to make way for his construction, “You can’t make an omelette without breaking some eggs” (attributed to Vladimir Lenin, among others). And he smashed many dozens of eggs to make his plans real.

Referring to Jacobs’ book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Campanella says “When Death and Life comes out in the ’60s, it’s a clarion call. It’s Martin Luther nailing those 95 theses to the cathedral door. The book is really the first cogent, accessible articulation of a whole set of ideas that questions the mainstream thinking about our cities.”

We are shown proof of the insurmountable folly of “urban removal,” evidenced by the blowing up of Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis. In film footage, we are shown that this was not an isolated example; we see the implosion of the Murphy Homes in Baltimore, Lakefront Homes in Chicago, and Mill Creek in Philadelphia dynamited into oblivion, admitting they were colossal mistakes.

It’s a complicated picture. Let us not forget that this East Harlem was not the desirable neighborhood it is today. El Barrio was one of the hardest hit areas in the 1960s and 1970s as New York City struggled with drug abuse, race riots, urban flight, gang warfare, the highest jobless rate in New York City, teenage pregnancy, crime and poverty, and a food desert. Tenements were crowded, poorly maintained, and frequent targets for arson. Public housing projects may not have been the ideal solution, but the problems were manifold and many were hungry for modern, clean alternatives.

The other big building issue is car traffic. The film shows the 1939 Worlds Fair General Motors Futurama, showcasing highways and pristine cities and suburbs. As the NYC Parks Commissioner, Moses was deeply involved with the fair, so might this be where he became enamored of the highway as the solution to the city’s ills? Is this when he transformed from the pre-war “angel” Moses who built public amenities for the common man to post-war “devil” Moses who destroyed the fabric of the city that is presented here?

There is no question that the automobile was given priority by Moses over the street ballet, but the situation is not always that simple. (In New York City, there is no alternative to surface delivery of goods throughout the city, even if you are able to transport by rail or boat to a depot.) The Cross-Bronx Expressway did bifurcate the Bronx and destroy neighborhoods, but can we really blame it for turning the South Bronx into Ft. Apache? No doubt it was a factor, but there was also the crack epidemic, white flight, abandoned buildings, gangs, redlining, arson (remember “the Bronx is Burning”?) and other social, economic, and political forces.

With a collective sigh, we are still relieved that the Lower Manhattan Expressway was never built, however the drawings shown to illustrate Moses’s plan are in fact an inventive, futuristic post-Moses scheme by Paul Rudolph funded by the Ford Foundation between 1967-1972 (Moses was out of power by 1968) which featured monorails, people movers, and a surreal Lego-like vertical expanse of housing lining the expressway.

Also more complex is the Moses Washington Square plan to extend Fifth Avenue so traffic could go through the park. The opposition by Jacobs in 1958 does not tell the whole story. In the film, there’s a provocative photo from that year sporting a banner that reads “Last Car Through Washington Square” indicating that traffic already traversed the park. In fact, Moses had been trying to revamp traffic plans around the square since the 1930s, first with a circle around the square nicknamed the “Bathmat Plan,” then the “Rogers Plan” in 1947 which also rerouted traffic around the square and removed the fountain. There was opposition each time.

As for other uses of documentary materials to bolster an argument rather than being accurate journalistically, this one is personal: I saw my apartment complex, East River Housing, clearly labeled, in a series of shots throughout the film, and used as an example of Moses’s public housing that destroyed neighborhoods; however East River was built as socialist housing by the International Ladies Garment Workers (ILGWU) and never part of the pubic housing system. No distinction was made, and it is a tower in the park design that actually works.

What Jacobs did was right for her neighborhoods, her time, and many axioms are universally true, but they have been taken to be gospel, much the way that modernism was perverted by developers to make easy, cheap, boring buildings rather than a gem like the Seagram Building.

The film is as much about the future of cities as it is about the past, but there are few suggestions about how to cope, except to go back to Jacob’s observations and let the old survive. It’s not about finding new solutions or even a new Jane Jacobs. It’s about codifying and simplifying her efforts. See what you think for yourself—it’s worth a look.

Citizen Jane: Battle for the City. Directed by Matt Tyrnauer

Other architecture and arts films of interest at DOC NYC (November 10 – 17):

- Ballad of Fred Hersch

- California Typewriter

- Chasing Trane

- David Lynch: The Art of Life

- Finding Kukan

- Ken Dewey – This is a Test

- The Incomparable Rose Hartman

- L7: Pretend We’re Dead

- Long Live Benjamin

- Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures

- Miss Sharon Jones

- The Nine

- The Pulitizer at 100

- Raving Iran

- Sacred

- SCORE: A Film Music Documentary

- Serenade for Haiti

Shorts:

- I ♥ NY

- L-O-V-E

- The Artist is Present

- The Creative Spark

- The Sixth Beatle

- To Be Heard

- Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present

- Winter at Westbeth

- Wonderful Kingdom of Papa Alaev