Graffiti in Chicago is not always vandalism. Though tagging, the stylized signatures sometimes used as gang markings, still pervade alleys and the occasional blank wall, graffiti has come into its own as public art. Whether on “permission walls” or commissioned by businesses, many neighborhoods in Chicago are filled with large-scale artworks that, until recently, were relegated to train cars and out-of-the-way places. But in neighborhoods on the near northwest side and near south of the city, fewer and fewer commercial walls are left blank. Partially as an attempt to stem random tagging and partially as an attempt to connect with young locals who may be future customers, businesses and developers are commissioning, or at least allowing,

massive works of graffiti on their property.

Along the Milwaukee Avenue corridor, through the Wicker Park and Logan Square neighborhoods, new midrise developments are being built every few blocks. As developers negotiate with locals who are often opposed to the new projects, new modes of community involvement are arising. In the case of one of the recent high-end apartment buildings, graffiti was at the forefront throughout early construction.

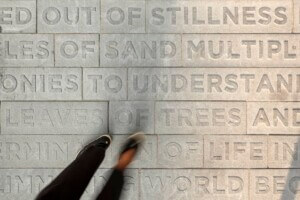

The 300-foot construction fence around what would become the L Logan Square, designed by Chicago-based Brininstool + Lynch, was handed over to local artist AMUSE126 to curate. Along with Galerie F co-owner Billy Craven, AMUSE126 gathered 10 local and national artists to produce a continuous mural on the fence. Though the fence would stand for only a few short months, the L has incorporated graffiti-inspired artwork into some of its common spaces, including its 200-spot bike parking room.

Less than a block away, a group of now-vacant buildings known as the Mega Mall is covered in technicolor portraits and vibrant lettering. Once a bustling flea market, the Mega Mall slowly declined until the last tenant left after the building was bought earlier this year. Once again, AMUSE126 and Craven were called upon to gather artists to cover the building in art. In late May, two dozen graffiti artist went to work on the building, working for free and providing their own supplies for the opportunity to paint along the highly trafficked street. At the time, it was anticipated that the building would be demolished shortly after the mural was complete. Yet delays in the permit process have led to the works staying up for over half a year, a very long time in terms of graffiti.

The project planned for the Mega Mall site has been dubbed Logan’s Crossing. Announced over a year ago, the project has not always been met with open arms by the community. Recently developer Terraco, Inc. and Chicago-based architect Joe Antunovich released new renderings based on community input over the last several months. Delays to the demolition of the Mega Mall along with other “permission walls” near the site have produced a half-mile stretch that would have been unimaginable in the past.

Chicago’s relationship with graffiti has often been a strained one. Through the 1980s and ’90s the city struggled with taggers, leading to the formation of the “Graffiti Blasters” under Mayor Richard M. Daley. To this day, unwanted tags will often be removed by the city’s teams, even if they’re not requested to be. The team removes over 60,000 pieces of graffiti every year. In 1992, the city passed an ordinance that would ban the sale of spray paint within city limits. This ordinance led to a lawsuit by spray-paint makers and sellers that would go all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1995, the ordinance was upheld, and for the last 20 years no stores in the city have sold spray paint. Recently, though, the same alderman who originally penned the ordinance has brought a plan before the city council to lift the ban in order to bring business back into the city. While the streets of Chicago have never been cleaner, it is arguable whether the ban had any major effect.

While the conversation about graffiti as a legitimate art form has definitely begun to lean heavily in favor of the much-maligned practice, the debate came to a head in 2010. Late one February night a crew of five graffiti artists painted a 50-foot wall along the then-new Renzo Piano–designed Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago. The graffiti protested the museum’s lack of recognition of graffiti as a modern art form. The act would make headlines and be the basis for a play entitled This Is Modern Art. The play itself was also controversial.

Well before this act of civil disobedience, one of New York’s more famous graffiti artists, Keith Haring, came to Chicago and was asked to produce a major piece. In May 1989, just blocks away from the Art Institute, Haring, with the help of 500 Chicago public school kids, produced a 480-foot mural in Grant Park.

Vandalism in Chicago can lead to felony charges. Yet with more “permission walls,” often designated by the city itself, and property owners allowing for graffiti, the definition of what public art is is quickly changing. As developers use graffiti to connect with younger communities, and businesses more regularly use it as street-front advertising, the street-art form is no longer only being associated with the disenfranchised or criminal elements of the city. Instead, perhaps graffiti is on track to skip the fine-arts scene and jump straight into the corporate art world. Whatever the case may be, graffiti is coming out of the shadows, and onto bigger things.