Fifty years ago, the term wellness—if it was used at all—essentially meant “not sick.” Then, throughout the ’80s and ’90s, the rise of gym culture and workplace wellness snowballed into an explosion of fitness boutiques in the early aughts. In city centers and upscale suburbs today, specialized fitness boutiques such as SoulCycle, PureBarre, Barry’s Bootcamp, and FlyWheel are nearly as ubiquitous as Starbucks. Combined with the rapid expansion of “health” branded grocery stores, an uptick in haute athletic wear, and a plethora of juice and smoothie companies, not to mention the surrounding media buzz, wellness has become not so much a trend as a booming industry.

Hotel conglomerates took note about a decade ago, assuming that the same kale-juice-chugging travelers frequenting SoulCycle and Whole Foods would want to stick to their wellness routines on the road. In 2010, Wyndham acquired TRYP, a subset of hotels that offers amenities like in-suite fitness equipment, healthy snacks, and an “energetic fitness center.” In 2012, Las Vegas’s MGM Grand introduced 41 “Stay Well” rooms featuring wellness amenities such as aromatherapy and air purification systems and access to Cleveland Clinic programs for “sleep, stress, and nutritional therapy.” In 2014, InterContinental Hotels Group launched EVEN Hotels with six locations in Norwalk, Connecticut; Rockville, Maryland; Times Square, Midtown East, and Brooklyn, New York; and Omaha, Nebraska. EVEN Hotels not only boast athletic studios, but also in-room personal training, group classes, and the Cork & Kale™ Market and Bar for healthy snacks. The branding, though aggressively green-washed, is apparently successful: Six more EVEN Hotel properties are slated to open in the next few years.

In 2017, fitness companies flipped the script. Luxury fitness brand Equinox recently announced it will open its first hotel in New York’s Hudson Yards development in 2019 with plans to open a second location in Los Angeles soon after. Equinox operates nearly 80 clubs in nine cities in the United States, with additional locations in Toronto and London, with approximately one million members overall. Although sources wouldn’t disclose which architects worked on initial designs, the revealed rendering shows a massive tower, expected to be home to a 60,000-square-foot “super gym” with indoor and outdoor pools in addition to the hotel.

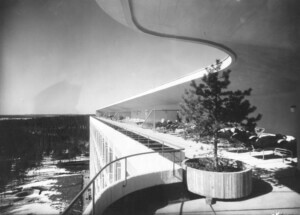

Equinox isn’t alone. Chicago’s Midtown Athletic Club, a tennis-and-fitness center established in 1970, is adding a 55-room boutique hotel on top of its facilities. Evanston, Chicago–based DMAC Architecture spearheaded the design of the addition and the redesign of the existing structure to create a 575,000-square-foot complex that will have 15 indoor tennis courts; four pools (including one that converts to an ice rink in winter); one full-size basketball court; several studio fitness spaces for yoga, Pilates, boxing, and spinning; locker rooms; retail and dining options; outdoor and lounge recreational spaces; as well as other hotel amenities such as meeting and banquet rooms, deluxe suites, and a penthouse presidential suite. “Rather than being 98 percent hotel with 2 percent amenity, [the Midtown Athletic Club] will be 96 percent amenity and 4 percent hotel,” said Dwayne MacEwen, founder and principal of DMAC architecture. “There are three floors of primary club space, with the third being an all-glass in-between space with the lobby, and the hotel component occupies floors four and five,” he explained. MacEwen emphasized that the prevailing design directive is to create something “intimate and choreographed,” eschewing a “big-box-gym atmosphere.”

Designing for wellness rather than merely fitness or hospitality involves a careful consideration of social and nonsocial areas. MacEwen and his team crafted specific spaces for conversation, like the monumental staircase on the second floor; spaces for solidarity, like the meditation room; and spaces for “being together, alone,” like the lounge. “We didn’t want to over program any one room—when you do that no one hangs out there—but we wanted to create an emotional impact through our use of materials, sense of compression, lighting, and wayfinding,” he said.

This strategy continues through the exterior of the landmarked building: The Midtown Athletic Club is located at a busy intersection in Bucktown, and MacEwen was cognizant of its impact on the neighborhood. “People choose to live in the city for a reason,” he said, “so we wanted to give something back to the urban street experience. It is more like an urban island oasis; you feel like you are a part of the city because you can see the traffic and feel the energy, but there is a solitude and quietness to it as well.” The Midtown Athletic Club hotel and renovation is set to be complete early this summer.

As hotels increase the amount of fitness and wellness offerings on deck, boutique fitness brands also feel obligated to provide key hospitality tenets—most importantly, forging a community with and among their members. Principal Chad Smith of Desbrisay & Smith Architects in New York has been working with boutique fitness brand Barry’s Bootcamp since 2012, both designing its studios and contributing to its branding. It is no coincidence that the tagline on the Desbrisay & Smith Architects website is “causing communities.” “We look at the organization of the space, as well as its touch and feel, and explore how the patrons come together and what happens before and after a workout,” Smith explained. This isn’t just “Kumbaya” feel-good vibes. “Boutique fitness companies want their communities to form a gang, not only because it has material impacts on their health and wellness, but [because] it increases retention so the businesses make more money.”

There is no singular approach when it comes to organizing spaces that make people feel as though their intraclub relationships are springing up organically. When Smith worked on CrossFit company I.C.E.’s New York location, he started by examining where and how clients interacted. “In CrossFit, people hang out and talk to each other in the workout space, so we wanted it to be chic and luxurious, very Manhattan,” he said. “Basically we thought, ‘If you had to pick a classic New York space to work out in, something that’s durable and glamorous, what would you choose?’ The obvious answer is Grand Central Station, so we picked up on its material cues, such as brass and dark blue paint.” But behind these sleek walls and floors, there is a lot going on: sound isolation, floating, spring reinforced acoustic floors, and superinsulated windows and walls.

Not only are these technological elements crucial for spaces like Barry’s Bootcamp, where 25 people run on 25 treadmills simultaneously within a mixed-use building, but they are also needed for when people sit completely still.

Meditation centers—that is, places where people go to sit and experience a guided meditation—are still new to the built wellness environment. When designing the Inscape Meditation Center in Manhattan, Archi-Tectonics founder Winka Dubbeldam spent months focusing on a seamless experience for clients. “It demands a different type of precision,” she explained. “If you meditate in all kinds of positions—walking, sitting, lying down—then you are very aware of yourself and the space around you. A few things became quite apparent. I wanted to create a continuum, an immersive environment: Walls and ceilings become one in the Dome; there is clean purified air; there is perfect sound and lighting. All the senses are soothed.”

Inscape has two meditation rooms: The Dome room is a large ellipse, while the Alcove room is smaller and wrapped in textural cloth. Both rooms feature color therapy lights, a smooth transition between the ceilings and walls, and carefully curated sound. “When we first soundproofed the space, we over-perfected it,” Dubbeldam said. “It was too soundproof! It actually hurt my ears. So we had an acoustics engineer come in and soften it and add a small amount of white noise to achieve a more comfortable silence.” The lighting was designed to avoid any pinpointed spots of light; rooms are equally lit, each with a soft horizon line around the Dome room where distracted meditators can focus their gazes and regain their senses of calm.

To achieve this level of design, Dubbeldam created a full-scale prototype in a warehouse in Brooklyn and meditated in it with Inscape founder Khajak Keledjian, who also founded the clothing boutique Intermix. “I see design as a process, a series of tests to achieve moments of precision,” Dubbeldam said. “It looks super simple, but it takes massive amounts of design and engineering. I really feel like that is where architecture should go, and, in our case, is going.”

Evan Bennett of New York–based Vamos Architects concurs.“Environments are shifting dramatically as technology shifts,” he explained. Bennett recently completed Honeybrains, a concept cafe in New York’s NoHo district that serves up information on brain health alongside healthy food options and a honey-focused retail section. Owned by two siblings—one who worked in neurology—the cafe features circadian lighting by Ketra disguised in a clever ceiling-light baffle. “We were careful not to have direct lighting, but instead created a honeycomb pattern that could reflect light off of the interior paneling,” Bennett said. “It lets us hide the track lighting, the AV system, and a projector up there as well.” Bennett admits that spending 30 to 40 minutes in a circadian-light-controlled system might not have major effects on one’s health, but he believes in Honeybrain’s mission to become a platform for discussing brain health and the possibilities of design that straddles the intersection of health and technology.

Though the wellness trend will play itself out and change over time, people-centric, health-focused design will endure in hospitality architecture. Combined with our current propensity toward mixed-use spaces and advanced technology, building boundaries will continue to blur—not only between hotel and gym, but across industries of all kinds.

Want more on wellness? Read how it’s influencing the workplace too.