When Hurricane Harvey strenghtened and redirected toward Houston, refineries and other petrochemical companies began a frantic scramble to shut down facilities before impact.

This process in itself produces notoriously high emissions (a lesson learned time and again from other hurricanes that have hit the Gulf Coast hard like Katrina and Ike), but the Texas metropolis faces another unique problem—Harris County and environs are home to some of the most densely-polluted superfund sites in the country, a legion of petrochemical waste pits and ponds monitored by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 13 of the total 41 sites were flooded in Harvey’s fallout, with the EPA unable to access many of the city’s sites, as reported by the Associated Press last Thursday. By Saturday, the EPA had examined two sites in Corpus Christi, found no flooding or leakage, and blasted the AP’s report in a public statement – notably without providing evidence to the contrary.

In their exclusive, the Associated Press described the “acrid smell of creosote” filling the air in a neighborhood situated between two superfund sites, the Sikes Disposal Pits and French LTD. They also took video from a boat peering into the 3.3-acre Highlands Acid Pit nearby—entirely covered by the roiling San Jacinto River, dredging up open toxic sludge. On Wednesday, the New York Times reported that in the Manchester neighborhood of Houston, levels of a carcinogen called benzene reached 324 parts per million, above the level at which safety workers are federally required to wear breathing equipment.

Scott Frickel, an environmental sociologist at Brown University’s Superfund Research Program, is concerned that the coverage of Houston’s post-Harvey recovery has been overwhelmingly focused on Superfund sites, important though they are. He has examined the response of federal regulatory agencies like the EPA to similar problems after Hurricane Katrina, the largest in the agency’s history at that time. A potentially greater danger, he argues, are the small, scattered industrial facilities owned by corporations and private entities.

In a study, Frickel and others found that 90% of historically existing industrial facilities don’t appear on regulatory hazardous site lists. Although there’s no certainty all these sites are contaminated, many probably are, and account for a large margin of undocumented emissions. Frickel explained: “In part these sites are ‘missing’ from regulatory oversight either because they are small enough to skirt the current reporting requirements or larger facilities that closed down prior to 1980’s when CERCLA regulations began and were redeveloped into some other land use. Also, it may be worth noting emissions reporting now is voluntary.” Their omission explains – in part, at least – why the EPA ignored historically industrial areas of New Orleans during the long recovery from Katrina, allowing the city to repurpose those same areas for housing reconstruction without risk studies carried out beforehand.

This feeling was echoed by Billy Fleming from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design, albeit with a concern about larger facilities. Fleming remarked that with facilities in almost every neighborhood of the city, he’d be hard-pressed to think of a place where residents shouldn’t be concerned about pollutants. Superfund sites aside, the EPA is not required to monitor emissions from those larger petrochemical facilities. But based on past precedent, we can expect any data provided by those 500-plus facilities with potential spillage to be sparse and unreliable.

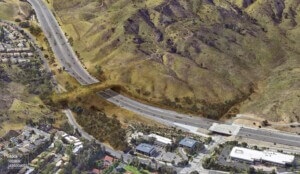

Fleming also broke down the legacy of urban sprawl and superfund sites on Houston in a recent Guardian article and on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/JooBilly/status/902349358410211328

Another point raised by Frickel was that, with the proliferation of private wells in Houston (also largely unregulated), any hazardous floodwaters that infiltrate them may pose additional threats, unless there was a commitment to chemical monitoring.

The long-term health consequences of a flood as devastating as Harvey’s are vast, ranging from breathing difficulty to liver cancer, and therefore difficult to measure at an epidemiological scale. Flood-induced mold is identifiable as an immediate nuisance for respiratory reasons; New Orleans residents reported a “Katrina cough” years after the storm.

The secondary disaster, other than immediate emissions from the shutdown of petrochemical facilities, are the chemical releases produced during the cleanup itself. These are wide-ranging and poorly understood: one example is the unexamined health outcomes of itinerant immigrant workers brought in to move debris and demolish damaged homes who are exposed to substances like asbestos from old buildings and vinyl chloride from newer ones. Because they move on to the next job in the next city, any health data disappears with them.

As we look at preventing human-made disasters like Harvey’s ruinous flooding from a planning standpoint, watchdogs, advocacy groups, and experts should be closely watching the EPA and the Trump administration’s attentiveness to environmental regulations as the chemicals continue their slow, inexorable spread through the water supply and air of affected areas.