After an arduous journey, Steven Holl‘s Maggie’s Centre is finally open. The new $10 million London care center, as with all Maggie’s Centres, will offer free emotional and practical support to cancer patients. This particular center, however, was marred by controversy—not something you would expect from a building designed to help sick people.

The center is the latest for Maggie’s, the charity founded by Charles Jencks in 1995 after his wife, Maggie Keswick Jencks, died of cancer. The couple believed in the uplifting power of architecture and have since installed more than 20 centers across the world, the majority of which are in the U.K.

Nestled into a neoclassical enclave on the grounds of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in central London, Holl’s Maggie’s Center very nearly never happened. For his design to be built, a rudimentary brick building from the 1960s had to come down. But that wasn’t the issue. Instead, the project’s adversaries argued that the new center didn’t connect with its surroundings.

This is nothing new with Maggie’s Centers across the U.K., even though Jencks has previously enlisted architecture’s A-list to design the structures, which are independent from nearby hospitals. Jencks has tapped Norman Foster, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Richard Rogers, Rem Koolhaas, and soon Daniel Libeskind, with a center in Hampstead. A page from Charles Jencks’ The Architecture of Hope: Maggie’s Cancer Caring Centres shows the site plan of all centers (before Holl’s was built). Here we can see green cytoplasm shrouding the Maggie’s Center nuclei; almost all the centers are one story and are surrounded by a protective grass lawn.

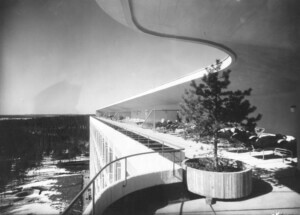

On such a tight site, there was no room for greenery, on the ground level at least. The first Maggie’s Center to reach three stories, Holl’s design incorporates a roof garden overlooking a centuries-old quadrangle that includes the 1740s church of St. Bartholomew-the-Less.

In a recent lecture at the World Architecture Festival, British architect and planner Sir Terry Farrell referenced Frank Gehry’s center in Dundee, Scotland (full disclosure: I work in communications at Farrell’s firm). He argued that the building exacerbated the dichotomy between the brilliantly designed and the under-designed. Who wouldn’t want a pristine lawn to protect from the encroaching drab contemporary hospital vernacular? At St. Bartholemew’s, which is Europe’s oldest hospital, such banal healthcare architecture cannot be found.

Despite this, Holl’s Maggie’s Center is at peace with its neighbors. After calls for modifications, the center shares a basement, toilets, and elevators with the adjacent 18th century Great Hall, a landmarked work of architect James Gibbs. Even these changes were nearly not enough. Holl’s design scraped through the second round of planning by one vote and even after that, a lawsuit was filed against the planners.

“I flew in from New York and they gave me three minutes in a courtroom. That was it!” Holl recalled, laughing.

Wrapping the building is a facade that at night reveals the squares of color embedded, offering a hazy glow. During the day, this color palette is significantly muted and the glass skin is more of a misty gray.

Outside, visitors can also see a rounded corner design, which is mirrored inside by a bamboo staircase that traces the perimeter as it winds upward.

Holl calls this the “basket” and a “vessel within a vessel within a vessel,” a reference to the concrete structural shell that lies between the glass and bamboo. No attempt has been made to hide this structure, and the result is a pleasing display of both tectonics and tactile design in harmony.

According to the Holl, the glass is a new invention. Comprising two layers of insulation, the embedded color film channels light out at night and blurs it during the day. The colored squares are also a reference to Medieval music’s “neume notation.”

“It couldn’t be glossy!” exclaimed Holl. “There are too many glass buildings today.” The architect continued: “Jencks thinks I’m a postmodernist, however, this building is for architecture a manifesto for the expression of materials; [it stands] against everything pomo was.”

“In my 40 years of practice, this is one of my favorite buildings I’ve ever done,” Holl said.