Today, almost a third of U.S. households are households of one, but the housing stock still reflects social values of the last century: Most homes are built for a married couple with children—the idealized nuclear family—yet these households now make up only 20 percent of families, down from 43 percent in 1950. While affluent singles may chose to live in a two- or three-bedroom house, lower-income individuals, or those who live in cities with white-hot housing markets, often have no choice but to co-house with others. An exhibition at Washington, D.C.’s National Building Museum responds to the changing American family and presents a compelling alternative: a home that can be rearranged for every stage of life.

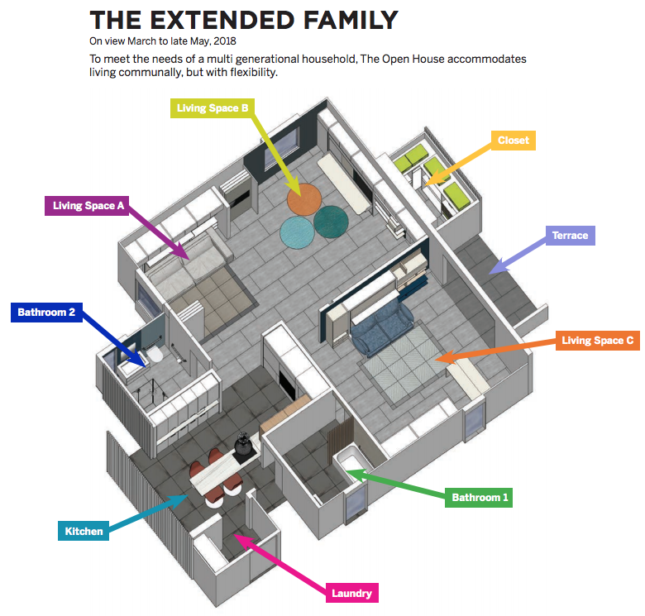

That model apartment, officially known as The Open House, is the centerpiece of Making Room: Housing for a Changing America. At slightly less than 1,000 square feet, it’s less than 40 percent of the size of the average newly-built U.S. home, but the unit feels spacious nonetheless, thanks to movable walls, retractable furniture, and clever built-ins. Last week, crews changed the apartment over from its three-bedroom setup (single people living together as roommates) to a multigenerational house where a mother, her children, and an elderly relative in a semi-private room can all live under the same roof.

“We wanted to promote a diverse set of housing options,” explained Jessica Katz, the executive director of Citizens Housing Planning Council (CHPC), a New York–based nonprofit that studies housing issues and collaborated with the National Building Museum on the exhibition.

The flexibility trickles down to the everyday, too. In the kitchen, the extended countertop can be lowered to table height with the push of a button, or lowered further for a wheelchair user to prep dinner. All the spaces are ADA-accessible, tricked out with Miele appliances and Ernest Rust cabinets that are opened with a soft touch. One wall over, the parent’s bed, a Resource Furniture Tango Sofa system, pulls up into the wall Murphy bed–style, leaving a couch and living room setup for daytime relaxation. A bunk bed in the children’s room, surrounded by built in cabinets for toy storage and a wall-mounted desk, does the same.

Adjacent to the kitchen is the grandparent’s bedroom, which functions as a small studio that can be closed off from the rest of the house for a more private retreat. Space-saving furnishings abound: A Giro Console Table folds out from the entertainment wall to become a narrow counter, and unfurls again to become a kitchen. A second bathroom, accessed from the studio and the kitchen, is wheelchair accessible. The dividers between all of the flexible spaces are the same moveable acoustic panels that segment conference rooms in convention centers, so the parent, for example, could host a sit-down dinner in her kitchen while the grandparent and the child in the household are asleep.

The Open House was designed by Italian architect Pierluigi Colombo and kitted out with donations from Resource Furniture, AJ Madison, Ceramics of Italy, Duravit, Ernest Rust, Hansgrohe, AXOR, and others (a full resource list can be found here). Colombo also designed the original Open House, which debuted in New York in 2013.

In many cities, building codes have a long way to go to catch up to the future of housing, however. The Open House was built up to NYC building code for “six different projects,” Katz said, so the team could re-arrange the rooms without incurring code violations if the house were built outside of museum walls. Instead of the costly, weeks-long renovation that usually accompanies a major interior renovation, it only takes museum workers around 22 hours to change the house over for each phase of the exhibition.

If the idea of a modular forever home seems far-fetched, Making Room’s final gallery includes examples of non-traditional housing across the United States that bridge the divide between concept and practice while honoring local zoning codes. There’s high-end ones like the Choy House, O’Neill Rose Architects’ private home for three generations in a part of Flushing, Queens that’s zoned for single-family houses, as well as more accessible options like Las Abuelitas Kinship Housing—a Poster Frost Mirto–designed community for grandparents and the children under their care in Tuscon, Arizona, pictured below. The hope, explained National Building Museum Curator Chrysanthe Broikos, is that these projects meet the needs of non-traditional families while demonstrating the need for residential zoning reform through quality design.

For those planning a visit, the Open House is on view through September 18. It has one more iteration to go through, though: In late May, the house will enter its sunset years, transforming from a multigen space into one for an older couple, with a studio apartment to rent out to a tenant or live-in caretaker. Right now, visitors can take a virtual walkthrough of the apartment’s current configuration, and more information on the exhibition can be found here.