“About time!” was perhaps the most common refrain on social media when it was announced that the 2018 Pritzker Prize had been awarded to the architect, B.V. Doshi, the grand old man of architecture from the Indian subcontinent. He is the first Indian to win the prize and its oldest recipient. It would be impossible to write a history of the modern architecture of India or, for that matter, of the non-western world, without acknowledging Balkrishna Doshi’s seminal contributions. His career spans nearly seven decades as an educator, urbanist and an architect, and his legacy undoubtedly transcends the Global South.

Yet for all the tributes that poured in, there was a eagerness to fit the contribution of the man and the significance of the award into a neat box. Robin Pogrebin’s piece in The New York Times, “Top Architecture Prize Goes to Low-Cost Housing Pioneer From India,” was particularly reductive, if not offensive, to those more familiar with the work. It is not unlike calling Beethoven, “a pioneer in concerto writing from Germany.” While both statements might be true, they betray an incredible myopia toward the breadth of their legacies.

When Doshi founded his office in Ahmedabad in 1955, the Indian state was not even a decade old. Mahatma Gandhi and his ashram in Ahmedabad had served as the epicenter of a great struggle against British imperialism. Doshi arrived in this city from Chandigarh, where Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, had commissioned Le Corbusier to design a new capital for the state of Punjab. Inevitably, the landmarks of the new nation liberated from European imperialism would now be built according to the doctrines of high modernism.

Doshi himself was a product of this movement, having worked for four years in the atelier of Le Corbusier in Paris prior to his arrival in Chandigarh. Even in India, modernism was seen as a tour de force that promised a new egalitarian social order, removed from the shackles of tradition. To be modern meant to embrace an architecture of European modernism and its associated dogmas of rationalist thinking, objectivism and tabula rasa planning, with an unfettered belief in progress and technology. For a nation recovering from colonialism, with great and diverse traditions in art, architecture and city form, reconciling these dogmas of modernist thinking took several decades.

Doshi’s work and legacy is a search for this reconciliation, between universalism and place, rationalism and what philosopher Paul Ricoeur calls ‘the mythical nucleus of humankind.” The quest embodied in Doshi’s oeuvre has also been the quest of his peers Charles Correa, Achyut Kanvinde, Anant Raje and Raj Rewal, to name a few. It has been a quest of not one, but several generations of architects from the subcontinent and the Global South at large, to create an ontological and literal framework for an architecture that is modern and yet rooted in place.

This involved acknowledging and reinterpreting elements from the rich traditions of Indian architecture –the courtyard, the jali (screen), a layered notion of enclosure, ornament and, very significantly, the plinth or the occupied ground. The treatment of the ground as a receptacle for the celebration of life is a critical aspect of Doshi’s work. It marks a clear break from the piloti and the grid–tools of Cartesian planning that favor the automobile’s hegemony over the ground.

Doshi’s School of Architecture (1972), Sangath (1980), and The Gufa (1990) reveal an evolution of an autochthonous architecture of the ground, which becomes one of the most significant attributes of these buildings. The School of Architecture presents an activated ground, a constantly changing datum with tactile inhabitation. This is already a distinct shift from the Institute of Indology (1956), one of Doshi’s earliest projects, or The Mill Owners Association building by Le Corbusier (1954) (a building that Doshi worked on as a project architect), which establish a strong single datum against the ground plane below.

Sangath (which roughly translates as ‘working together through participation’) marks a true departure from the architectural tropes of Corbusier and Louis Kahn–the coming into being of a distinct architecture which is both modern and deeply rooted in place. The ground and the building are now inseparable and symbiotic. Landscape becomes the primary architectural mediator. The building is perceived as a rich topography of occupiable plinths culminating in vaulted porcelain mosaic roof forms that frame the sky. It is an architecture of multiplicity, tactility, ornament and myth. When the project was under construction, Doshi encouraged local craftsmen to leave their own creations in the landscape of the building, giving agency to the artisans. The waste of chiseled stone chips becomes an incredibly beautiful embellishment within the landscape. Upon entering the premises, you enter a haven–a world within a world. Programmatically, the building works not just as a studio but as a real celebration of life–a living ground for exhibitions, performances and festivities.

In reflecting on Doshi’s work on housing, the French philosopher Paul Ricœur comes to mind. In History and Truth (1961), Ricoeur says, “The phenomenon of universalization… constitutes a sort of subtle destruction…of the creative nucleus of great cultures…the ethical and mythical nucleus of mankind. Everywhere throughout the world one finds the same bad movie, the same slot machines, the same plastic or aluminum atrocities, the same twisting of language by propaganda.” It is striking how prescient Ricœur is today in an era of fake news and climate change. Everywhere one finds the same twisted architectural forms, the same placelessness, the same erosion of public space and public life, the same universal crisis of housing, and the replacement of housing by speculative real estate in global cities from London and New York to Shanghai, Lagos and Mumbai.

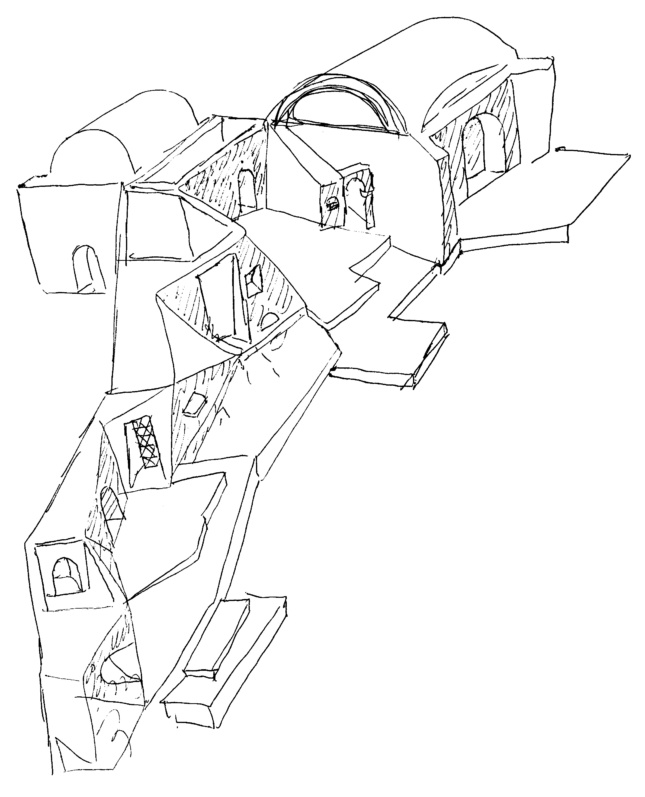

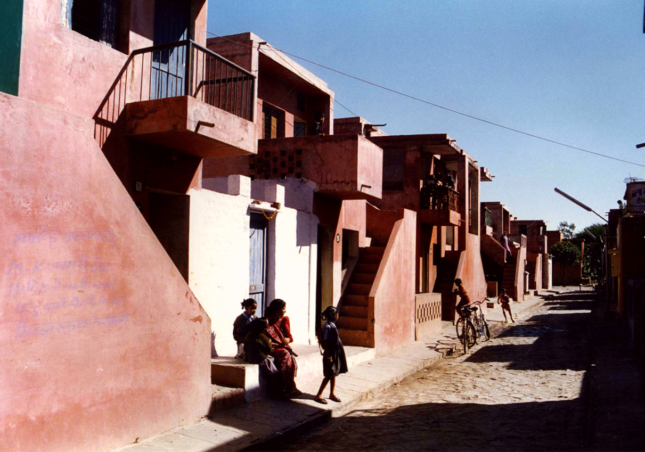

It is in this light that Doshi’s low-income housing in Aranya should be considered. The Aranya project is a highly sophisticated design for over 6,500 dwellings. For a site and services project, it breaks from typical gridded layouts that maximize rationalization and efficiency. Instead, the project provides an urban armature where a range of open spaces and pedestrian pathways intersect and connect residential clusters to a central spine.

Incrementality is the defining attribute of the project. Users are encouraged to add rooms to the service core of their house over time. Eight demonstration houses were designed by Doshi to illustrate the array of available options, from one-room shelters to more elaborate homes. Cross-subsidies and financial structures were put into place to encourage people to build their homes incrementally. This they did, and Aranya today is a thriving city of over 80,000 people. The project has created common spaces where people from varied castes and diverse religions mix and cooperate. Social cohesion is fostered through the very framework of the project–a crucial aspect that is easily overlooked in its descriptions.

That architecture can and should have a socially progressive agenda was, after all, a defining attribute of the modernism–to bring design to the masses, to produce not only a new aesthetic, but also a new egalitarian order. Form thus became an instrument of reducing social inequity. The canonical architects of the time engaged in feats of social housing, such as Weisenhoff Seidlung, the Unité de Habitation, Byker Wall and PREVI Lima. Aranya belongs to this lineage of architectural agency.

Today, an architecture of social cohesion has given way to the architect as a celebrity superstar, complicit with neoliberal agendas, designing condominiums for the one percent. Form has utterly lost its social agency and become the perverse weapon of increased social inequity. Never before has the architect seemed more impotent in the face of global crisis–ecological, political and social. It is clear that architecture today needs less autonomy and greater spatial agency. This means a deeper engagement with forms and practices that offer modes of resistance to neoliberal orders, and less collusion with the forces of capital. For an architect who has completed over one hundred projects in nearly seven decades of practice, Doshi has yet to design a luxury condominium or a glass skyscraper!

In belatedly acknowledging Doshi’s legacy, the Pritzker Prize finally brings attention to a great body of work. It also exposes a certain state of contemporary culture where practices of resistance are few and far between.

Finally, in an age of toxic work cultures and the erosion of family life, the life of B.V Doshi also has something to teach us. This is reflected in his belief that great architecture is attainable not in spite of family life but because of it. Speaking at the Royal Academy of Arts last year, Doshi said that living together within an extended family remained one of the greatest influences of his life, where he “learnt about cooperation, tolerance, togetherness, humility, generosity, and interdependence.” While much is made about Doshi’s associations with the masters, it is the women in his life who need to be celebrated–his three daughters, wife and mother-in-law. He is surely the only Pritzker Prize winner to have lived with his mother-in-law for 38 years. “I learnt so many things from her simplicity, humility… She was fantastic!”

Doshi’s life and work are imbued with an ethos that integrates the quintessential qualities of architecture–form, space and light–with the quintessential attributes that make us human, to create institutions and places of lasting meaning and value; an architecture of place in an age of placelessness. This, in the end, is perhaps what makes Doshi so relevant to contemporary culture today, both in the east and the west.

Sarosh Anklesaria is a Brooklyn based architect and Visiting Assistant Professor at the Pratt Institute. Sarosh spent eight years at CEPT University, which was founded by Doshi, and has worked as an architect at Sangath, the office of B.V. Doshi.