When I first arrived in Ahmedabad, India by train nearly twenty years ago, loaded with a backpack and a collection of books from which to teach for the first time, I asked the rickshaw driver if he knew where Sangath was located.

“Oh, you are looking for Doshi-ji?” he quipped. “Doshi-ji,” the ‘–ji’ signifying both respect and an honorific for an elder or person of standing, “is most important shiksak (a word suggesting teacher) and vaastulkar (architect/engineer).” That a driver in a burgeoning city of millions might recognize the location of Balkrishna Doshi’s famed atelier, as well as the man himself, did not occur to me as unusual until much later.

Having known of Doshi-ji from gazing upon Chandigarh in a number of darkened classrooms as a student, I eventually made a pilgrimage to the “new”capital city of the Punjab upon arriving in India, which Doshi had managed. There he was in photos examining drawings alongside Le Corbusier, sitting at a drafting table in Paris, observing a construction site in Bangalore; his name echoed among those architects and students I met: “You must go to Ahmedabad,” they implored. I remained skeptical. And so it was two years later, when I returned to India, this time to teach at CEPT (which later became a university), an elegant brick and concrete architecture and planning school conceived and designed in part by Doshi, that I finally went to Ahmedabad.

Until then, a number of my teachers had emphasized a rethinking of modernism’s legacies and impact. Such notions informed the first classes I taught at CEPT, one of the reasons I set off for South Asia in the first place. Here, without the distraction of every emerging trend, it seemed one might be able to both yield to and observe closely how and why architecture and urbanism informs the complexities of daily life. Yet it seemed I could not escape, in every discussion and desk crit, the mention of Doshi-ji.

His name and his ideas are a force in a school that bears an unerring vision of moving architecture beyond the conventional dialectics of here and there, them and us. I was living and working within his vision of a holistic architecture bearing the imprint of (Indian) society’s inward turn toward the maintenance of mythmaking. Merging a landscape as much informed by cosmology as that of a not-so-ancient city’s sprawl, the school had become my center of gravity. By this time, I had sipped chai alongside the morphological experiment of the “Gufa,” or Amdavad-ni-Gufa, Doshi’s collaboration with the esteemed artist MF Husain; I had walked past the stepped shelled-facades of his studio, Sangath, en route to my favorite dhaba on Drive-in Road. These were familiar landmarks. But nothing prepared me for my first meeting with the man whose presence had long preceded him.

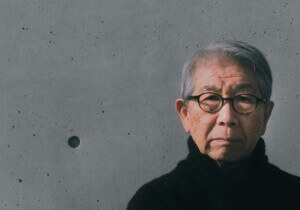

(Courtesy VSF and Pritzker Architecture Prize)

I had asked members of the school to introduce me to Doshi-ji. After a few months, I found myself sitting one very hot day in the cool hush of his studio. The atmosphere was charged with the silent attention of men and women working on drawings and models for the Diamond Exchange in Mumbai. Doshi-ji appeared and immediately asked me what buildings I had seen, what books I was reading. I rambled through a list, and soon was asked to sit with a group of young architects at the edge of a long table covered with books, our heads turned daily toward the making of drawings.

However, I did not last long in Doshi-ji’s studio. Perhaps my hubris prevented a longer affiliation with him. I did not understand the devotional attention to the “guru,” to the “master” whose teachings were the stuff of legend. Did I think I could not learn from him? Even with all the time I had spent at CEPT and elsewhere that possessed his hallmark spirit, I was not immediately converted. On every occasion I was asked to participate on a design jury, Doshi-ji would glare at me or ignore me altogether. I tried to counter him with misplaced theory on multiple occasions, unsuccessfully.

I have reflected on these decisions over the years. So much of what we think of the great architects and their embodiments happens after the fact, over time, even if immediacy does not negate experience. Rhetoric cannot hold sway with an architect such as Doshi, whose lifelong philosophy to educate through and by building drives an unerring attention to the built environment as a mirror of our knowledge…or lack thereof.

More recently, I have had the great privilege of visiting Doshi-ji again at his model-filled studios of Sangath as well as at the exhibition of his work at Shanghai’s Power Station of Art, organized by Khushnu Hoof. We laughed at my early inattentions. Our discussions have centered on the agency of the visual in relation to the question of inhabiting space as a universal and/or ethical condition. He has asked me how to move beyond the degradation of belief to imbue architecture with the capacity to transform society at multiple scales. With inspired words and aphorisms, Doshi insists on recognizing the self as inhabiting multiple contexts. His projects are intimate glances at the character of a man whose work is revolutionary for its ability to be present and to disappear at the same time. Doshi-ji, Abhinandana, Mubarak, congratulations on your extraordinary achievements and for teaching all of us how to see for ourselves.

Sean Anderson is the Associate Curator in the Department of Architecture and Design at The Museum of Modern Art.