When news broke last week about JP Morgan Chase’s plans to tear down 270 Park Avenue, otherwise known as the Union Carbide Building, by Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM), the New York architecture community predictably went up in arms. Critics like New York Magazine’s Justin Davidson lambasted the plans as “obscene,” while Curbed’s Alexandra Lange called the plan “shortsighted.”

But after the initial shock at such a huge building being torn down has faded—it would be the tallest building to be voluntarily demolished—there has still been little to no convincing argument offered for JP Morgan Chase to save the building.

The Union Carbide building should be torn down. In fact, we should cheer as it falls because it represents the worst of midcentury American corporate architecture, something that at the time was totalizing, banal, repetitive, and dogmatic—when everything began to look similar.

The Union Carbide building is derivative of the Seagram Building just down the street, an exemplar of a time when copying Mies had gotten completely out of control. In fact, Stanley Tigerman’s “The Titanic” addressed exactly this phenomenon: Mies was great, but his copiers were not. Buildings like Union Carbide are what inspired Tigerman and his peers to develop architectural postmodernism.

By defending this building, critics are creating an echo chamber reinforcing bad corporate architecture that offers very little to architectural culture. By 1961, almost 70 years of seminal modernism had completely altered the way we build and the way we see our cities. Just in the United States alone, there are many important projects of the movement, including Mies’ Farnsworth House (1951), Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Building (1939), and a number of projects in California by Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra that stand as important works that need to be saved to preserve this history. A nondescript corporate box from 1957 that isn’t even one of the most important buildings on its own block—the Seagram Building, the MetLife Building, the Lever House, and the PepsiCo Building are all better—shouldn’t be cried over.

The Union Carbide Building is an offender of the high modernist co-optation of the guiding principles of Modernism—a movement originally fueled by a socially progressive agenda (better, cleaner, more egalitarian cities) and made possible by radical innovations in building technology, most notably machine precision and mass production. Davidson rightly notes that “before the 1950s, builders could hide approximations and errors with ornament or tolerant stone.” However, this disregards that fact that buildings like 270 Park paved the way for the co-optation of the original machine aesthetic of mass production in modernism. What started as something beautiful and new became something developers used to cut costs. The result is today’s banal stream of terrible, stripped-down glass boxes that litter our skyline today: the late capitalist use of the modernist aesthetic and efficient production process to justify cheaper and cheaper buildings.

Davidson claims, “To demolish one of the peaks of modernist architecture in the name of modernity is obscene, a sign that you consider your city disposable.” Unfortunately, this is an odd conflation of the idea of modernity and the contemporary. In architectural terms, modernity and modernism are historical periods, linked by the advent of the industrial revolution and the refinement of the machine aesthetic alongside it. However, Davidson’s linguistic trick falters when we realize that tearing down 270 Park would not be a quest for modernity, as we are now postmodern or something even further removed from modernity. Once we can move beyond an ideological idea that modernism is still important to the contemporary, we can treat it fairly as what it is: a historical style.

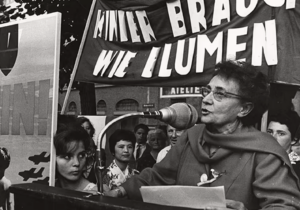

Furthermore, 270 Park and many other midcentury buildings were built by the most ruthless cabal of capitalists the world has ever seen. They did it with style, but let’s not forget that the Madmen of this era reinforced a power structure that we are still struggling to shake off today. Theirs was a world fueled by misogyny, exploitation, white supremacy, and capitalist imperialism. Union Carbide is or should be notorious as the perpetrator of the worst industrial disaster in the history of the world, the Bhopal disaster, in which almost 4,000 workers and at least 15,000 people total were killed by a toxic gas leak at the Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. Midcentury clients were sometimes bad people with good taste. We shouldn’t tear the building down because of Union Carbide’s transgressions, but we should not assume that JP Morgan is a new evil desecrating some holy landmark.

In fact, demolition is the only logical conclusion for a building like Union Carbide. It is a structure built precisely for the logic of the market to consume it: Capital exploits and extracts maximum value from whatever it uses and leaves behind a smoldering husk once it has been deemed worthless. Why not just let 270 Park die a natural death at the hands of the 21st century equivalent of Union Carbide: a multi-national bank? It’s really a beautiful story if you think about it correctly.

It is true that this is a wildly wasteful proposal. But this building can be torn down as an exercise in tearing down such tall structures. The demolition could offer a useful case study to learn from. As skyscrapers age, this will become an important preservation issue. How will we deal with tall buildings in urban settings that can’t be imploded? What are the techniques for taking away glass at 40 stories? How does a curtain wall removal differ from a typical window assembly?

This is not always a question of waste, either. How do we take down tall buildings that are severely damaged by fires, earthquakes, or other disasters? If the demolition is done correctly, companies like Rotor Deconstruction could also salvage much of the architectural heritage by saving a good amount of the building material, which could find new life in newer buildings. A strong proof-of-concept would help the entire profession.

The Union Carbide building is the type of building that really isn’t that important, but has somehow become more revered because it is located in New York. However, this building is not any more remarkable than many like it all over the world. This myopic obsession with New York’s past holds it back. Even Ada Louise Huxtable—who Lange quotes in her attempt to rationalize saving Union Carbide—once said in 1957, the year 270 Park was completed, “Today the old Park Avenue is being buried with remarkable and ruthless efficiency…For we must no longer just bury the past, we destroy it to make room for the future.” We have to wonder what she would think of the predicament today.

However, just because 270 Park is not worth saving does not mean that what replaces it couldn’t be worse. The big question now is: What’s next? Architect Andrew Zago likes to say, “It’s ok to tear anything down, as long as you replace it with something better.” This is likely not JP Morgan Chase’s mantra, but the banking giant certainly has the resources to choose any architect it wants. How do we persuade Chase to hire an architect who will guarantee design excellence? One way is if the Department of City Planning were to hold the firm’s feet to the fire. On such a high-profile project at the beginning of a neighborhood-scale transformation that the de Blasio administration seems invested in, DCP should have a say in what goes up. And they should care about design excellence. Let’s redefine what it means to be contemporary, not dwell on what it means to be “modern.”