Carl Laubin, a British-American architect turned full-time painter, has dedicated the last three decades of his professional career to the painting of architectural capricci, bucolic landscapes and portraiture. An architectural capriccio encompasses the imagined assembly of buildings across fantastic landscapes.

Laubin’s choice of subject matter jumps between historical periods. What seemed chronological at first: Andrea Palladio, followed by Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor, jumped to Neo-Classicists Claude-Nicholas Ledoux, Charles Cockerell, and Leo von Klenze, then to Edwin Lutyens, with Post-Modernist John Outram and Leon Krier thrown into the mix. Currently, Laubin is working on a capriccio of John Nash’s work.

On average, these capricci require one-and-a-half to three years to complete, depending on how prolific the subject was, with time split evenly between the drawing and painting periods.

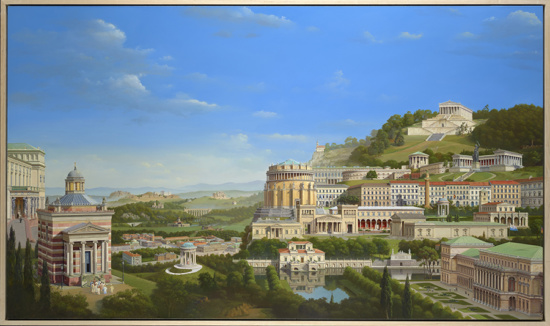

Although the bulk of Laubin’s capricci focus on the work of historic designers, he has produced paintings that combine a multitude of contemporary architects. A Classical Perspective comprises architectural pieces designed by the winners of the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture’s Richard H. Driehaus Prize. Beginning with the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in the foreground, the oil painting collages notable works by Robert A.M Stern, Demetri Porphyrios, Michael Graves, Abed-Wahed El-Wakil and Quinlan Terry, to name a few.

Educated at Cornell University, Laubin describes his early painting as “a second, secretive life,” one conducted outside of Cornell’s then-rigid modernist education. Laubin graduated from Cornell with a B.A of Architecture in 1973, and subsequently decamped to England to join Douglas Stephen and Partners, Architects and Civic Designers (1973-1983) and later Jeremy Dixon/BDP (1984-1986). While working as an architect, Laubin painted in secret, waking at dawn to hone his craft before going to work.

Seeing as how the production of capricci is a centuries-long tradition, Laubin cites a number of artists as influencing his style. To Laubin, Piranesi “was and remains an example of how to be liberated from the constraints of reality in creating an imagined world in a drawing or painting, and even how to be liberated from the constraints of drawing itself.” Canaletto’s grand paintings of Venice and London are firmly behind Laubin’s composition of urban scenes populated with bustling denizens. In his fantastical characteristics, the phantasmagoric visions of Joseph Gandy are plainly evident.

While Laubin insists that there is no clear methodology to his process of creating a capriccio, he has a general approach to each project. The first step is the steady amassing of information on the subject matter. This initial creative moment includes the reading of primary and secondary sources, visiting individual sites, and sketching as much of the architect’s canon as possible. Subsequently, each sketch is collaged and re-collaged until a suitable format is found, representative of an architect’s professional timeline as well as the general hierarchy of their work.

In creating the landscapes for his capricci, Laubin follows a recipe for a classical landscape given to him by postmodern architect John Outram. In Outram’s view, one always crossed a river or a bridge into a classical painting, and then ascended through various levels of civilization from cave dwellers, through agrarian societies, to urban areas, and finally places of worship at the highest point. In tandem with this formula, Laubin draws upon the landscapes surrounding individual sites and fuses them into the overarching collage of elements.