After a major, failed expansion attempt a few years ago, the Frick Collection, that venerable Upper East Side museum and library, revealed its latest renovation plans last month. The Frick tapped Selldorf Architects and Beyer Blinder Belle to bump up the landmarked building’s footprint by ten percent, while sinking most of the rest of the program underground. Now, a few days before the architects present their ideas to the city’s Landmarks commission for approval, more details on the addition and renovation have emerged.

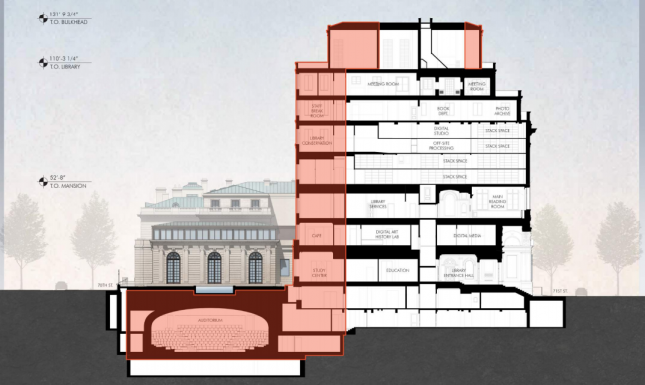

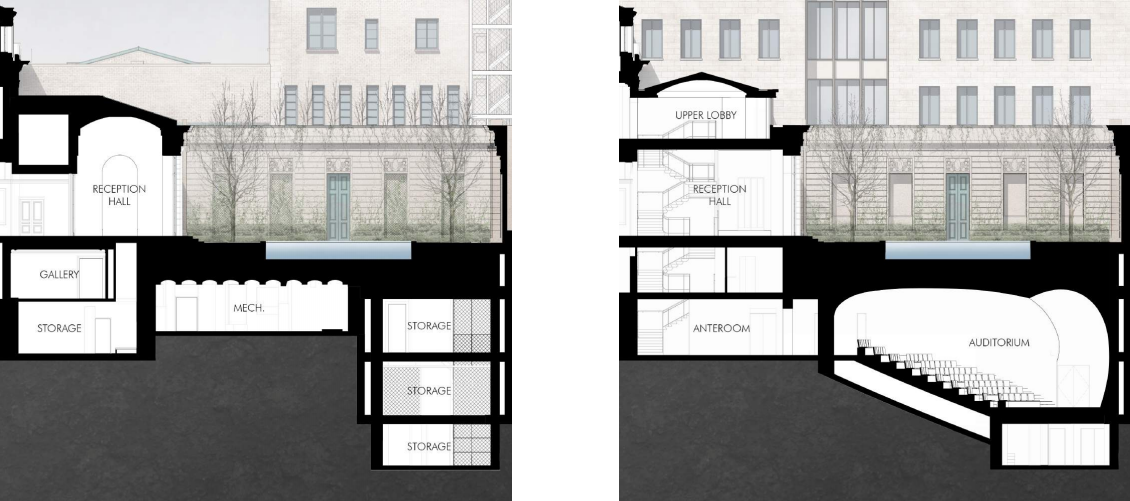

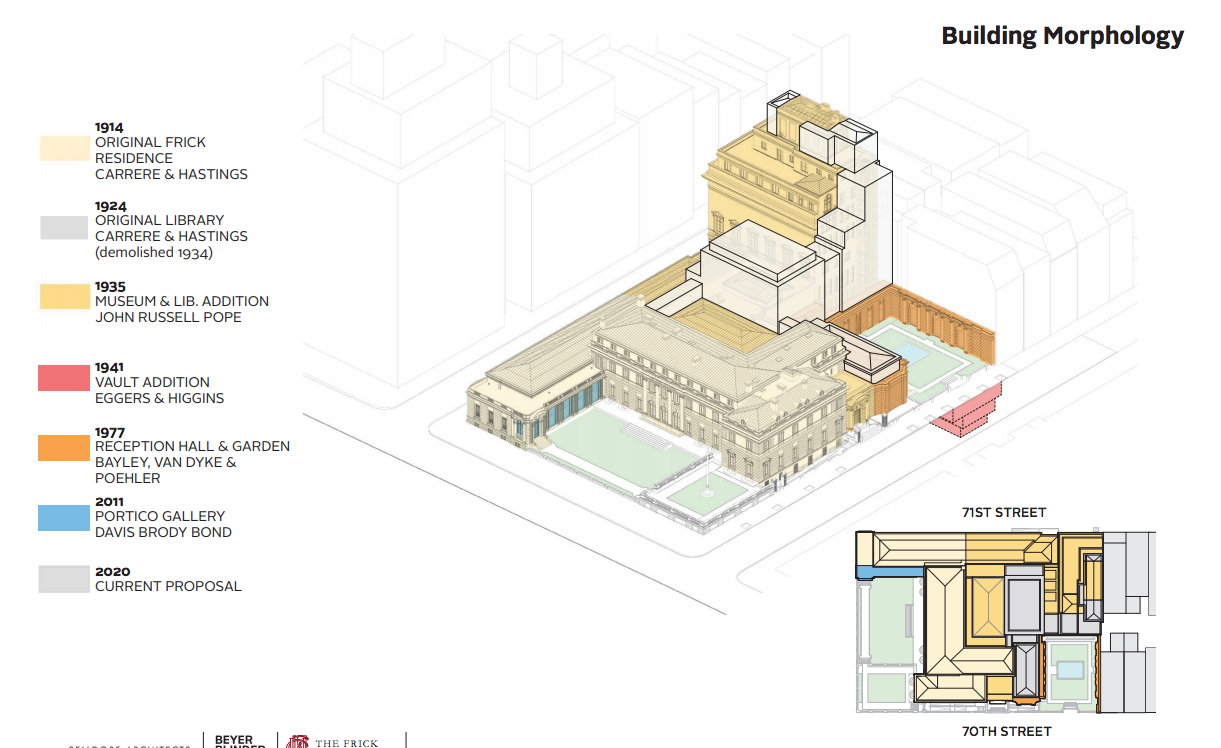

When the Frick went public with Selldorf’s design in April, reactions were mixed, but mostly positive. The tallest addition will grow two stories from the building’s music room, while an addition adjacent to the library will top out at the same height as that building. The above-ground additions should preserve sightlines into John Russell Page’s gated garden, while a below-ground auditorium and galleries will add give the Frick more space for events and shows. A major goal is to improve the flow between rooms, which will be achieved in part by linking the new second floor galleries with the enlarged lobby and the auditorium beneath the garden.

That space is badly needed. The institution is mounting more exhibitions and welcoming more visitors than any time in its history, but its building is strained at the seams. The Frick says its galleries are too packed, and the lightless ones below ground are less appealing to visitors. Wheelchair users must take an unglamorous ride in the service elevator to reach the main entrance. Workers in the conservation areas, meanwhile, labor in dark, cramped offices far from the service elevator. And there’s nowhere to get coffee—unlike most other museums, the Frick doesn’t have a cafe.

Before building out below-ground spaces to make way for a 220-seat auditorium, a larger reception hall, and an upper lobby, the Frick plans to document and restore Page’s design. The sculptures, reflecting pool, and north wall will be dismantled and rebuilt (the latter with a different design), while the paths will be restored to their dimensions with new gravel. According to the presentation submitted to Manhattan Community Board 8, which held a public meeting on the plans earlier this month, the garden’s plants and trees will be “retained to the extent possible or replaced with appropriate species.”

As part of the Upper East Side Historic District and as an individual landmark, any changes to the Frick have to be approved by the city’s Landmarks commission. Carrère and Hastings, the same architects behind New York Public Library’s 42nd Street main branch, designed the original, now-landmarked Beaux Arts home for the Frick family in 1914, as well as an attached library in 1924. (That structure was demolished a decade later to make room for a museum and library conversion by John Russell Pope.) These buildings, plus 1977 and 2011 additions by Bayley Van Dyke Poehler and Davis Brody Bond, respectively, comprise the majority of the significant, still-visible work on the site until now. Although the exterior was landmarked in 1973, the interiors not protected.

In mid-May, CB8’s Landmarks Committee rejected Selldorf’s designs (PDF), while the full board of CB8 couldn’t come to a consensus on the appropriateness of the expansion when it considered the matter a few days later. Although community board votes are only advisory and non-binding, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) takes their thoughts into account when it makes its decisions on whether to modify a landmark.

Overall, most preservationists prefer Selldorf’s design to the Davis Brody Bond scheme the museum proposed a few years ago, but there’s concern that interior renovations will sacrifice period interiors like Russell Pope’s music room for white-box galleries and splashier events spaces.

There’s also growing concern around the Page garden. Current plans scuttle northern end of the 4,100-square-foot green space, which features trees of different species planted against a wall. Here’s what landscape architect Laurie Olin had to say about Page’s work in a recent letter to the Frick trustees that was printed by landscape preservationists at The Cultural Landscape Foundation (we’ve excerpted the letter, below):

I have always liked this garden and admired Page. It is inconceivable to propose to eliminate the northern planting above and beyond the wall that Page used to give an illusion of depth and of a garden beyond it to the north. The pear trees, wall, planter, and door are key contributing elements of the garden. His famous asymmetrical planting of four trees of different species plays off not just against the rectangular basin but also this uniform layered plane of green that one thinks the door goes into. It’s a thought worthy of Borromini if he’d had a green thumb, and a mark of Page’s genius and subtlety. These elements are not expendable, but the conclusion of a remarkably witty and brilliant solution to a difficult problem, that of a tiny urban space hemmed in by buildings – one that has challenged designers and artists since Roman times. I have on numerous occasions in my teaching graduate students in landscape architecture and garden design over the decades used this as an example of how a skillful designer can overcome the awkward problem of such a small space in a dense urban setting.

I urge you to save your Russell Page garden, the whole garden, not just some of it.

In its testimony to the LPC, historic preservation advocacy organization the Historic Districts Council (HDC) suggested the shelf above the north garden wall, now festooned with trees, be maintained to add interest to the library’s rear wall. Meanwhile, in a long letter to the LPC chair, Henry Clay Frick’s great-granddaughter Martha Frick Symington Sanger wrote expressed disappointment in the “over-the-top architectural expansion that promises to alter the landmarked buildings and severely compromise the historic Russell Page Garden [sic].”

For those who want to have their say on the Frick, the LPC is hearing from the museum, the architects, and the public at its May 29 meeting. The hearing begins at 9:30 a.m., and the exact time should be posted on the agency’s website today.

At meetings with preservationists at the Frick in May, HDC Executive Director Bankoff confirmed that Selldorf Architects principal Annabel Selldorf said the designs were “schematic”—typically, architects seek the LPC’s approval when their designs are final.

While the Frick has done a “very good job” at community outreach, given the complexity of the proposal, “I would be shocked if the LPC approved this in one hearing,” Bankoff said.