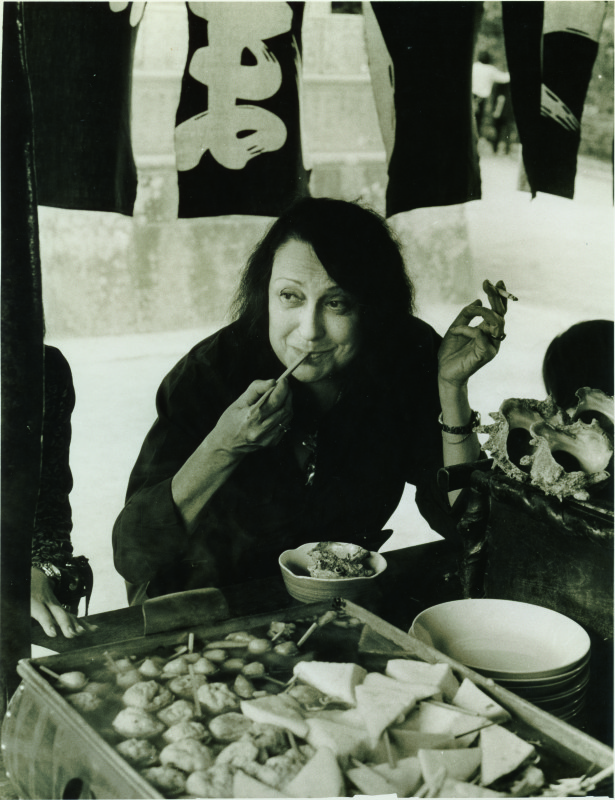

The following is a roundtable discussion among three Brazilian and Italian architects and scholars on the legacy of Lina Bo Bardi and the state of preservation of her works in Salvador de Bahia.

Giacomo Pirazzoli: An architect and an immigrant, Lina Bo Bardi moved from Italy to Brazil in 1946 to start working in San Paulo. In 1959 she was invited to work in Salvador de Bahia, where she first became acquainted with Afro-Brazilian culture. Among the most relevant works she achieved while there, the Museum of Modern Art (MAM) at the Solar do Unhao—a former transfer point for sugar shipment—was re-designed in a few steps. Intriguingly enough, she declared “this is not a museum” since it had no collection; instead Lina thought it should have been “a center, a movement, a school,” at least according to the research begun in 1946 by her husband and partner-in-crime Pietro Maria Bardi.

Four years after the Centenário de Lina Bo Bardi (1914-2014): Tempos vivos de uma arquitetura exhibition in Salvador that focused on the conservation of Bo Bardi’s work, the windows at MAM toward the bay have been capped, invasive air conditioning ducts have been installed, and paintings are actually hanging on the walls as in a bourgeois living room, something Bo Bardi refused for years. How would you comment on all of this?

Ana Carolina Bierrenbach: In 2015, together with Eduardo Rossetti (University of Brasília), I wrote an article for the architecture magazine RISCO, published on the occasion of the centenary of Lina Bo Bardi you mentioned. In that essay, we put forward some observations that I believe are still true today. We emphasized the fact that Lina finally got recognized in Brazil and abroad, sometimes reaching a level that we could define as idolatry, which we consider even excessive.

Her works in São Paulo got appropriate care, as they have already had restoration, or soon they will have. Perhaps this concerns the role of architecture in São Paulo, which has a more widespread attention among local people, unlike what happens here in Salvador where perhaps people do not recognize how important architecture can be.

Back to Bo Bardi’s buildings in Salvador. It seems to me that the situation is complicated at MAM; now it seems that the sculpture garden and the cinema are about to be reopened. A few days ago, we saw that the roof has been completely rebuilt, while the pier is in a very precarious state. Certainly MAM has for a long time had a crucial role for the city, but, unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be true any longer.

Nivaldo Vieira de Andrade Junior: I agree that in São Paulo the work of Lina Bo Bardi is better preserved than in Salvador, perhaps because in São Paulo four of her buildings have been listed by IPHAN, the Brazilian institution that protects cultural heritage. One more proof of this better care for her work in São Paulo is the recent reconstruction of her original display at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), as well as the ongoing conservation projects both at MASP and at the Glass House, where the Bardi couple used to live and is today the headquarters of the Instituto Bardi-Casa de Vidro. It is also important to note that both conservation projects are under a particularly qualified supervision, being supported by the Getty Foundation under the Keeping It Modern program.

Moreover, in Salvador, it is not just about the actually disruptive changes on Bo Bardi’s display design at MAM that you previously mentioned. It is also worth noticing the largely oversized ducts of the air conditioning system actually installed within Gregorio de Mattos Theater, where a polycarbonate “box” with a metal structure at the upper floor leads to a full misperception of the helical concrete staircase, including its red central pillar.

GP: Let’s go on to consider another case in Salvador, the 2014 intervention on the Casa do Benin, a peculiar culture-crossing bridge connecting Africa and Brazil. There, the woven straw with which Bo Bardi covered the columns has been eliminated. Also, galvanized open channels for lighting purpose have been added apparently at random, sharing nothing with the pre-existing red painted ducts. The exhibition curated by Pierre Verger and designed by Bo Bardi has also been altered to include works of dubious value. Finally, the large palms in the external area have been replaced with small potted ones. I believe that in various places on the planet, this supposed maintenance intervention would not be accepted, given the outcome.

Of course I agree that these works need to be listed by IPHAN. In addition, I believe that in order to intervene on Lina’s works, so rich in intercultural references, appropriate scientific support is needed, at least to provide research materials. In this sense both Docomomo and Instituto Bardi-Casa de Vidro should play a role, somehow consolidating the work of the Getty Foundation’s “Keeping It Modern” program.

ACB: Actually, I believe these interventions demonstrate a lack of proper understanding of Lina’s work. Her design choices, from the more specific ones, such as the superimposition of woven straw on the columns of the Casa do Benin, to other more generic ones, such as the use of the thin-armed mortar walls developed by the architect João Filgueiras Lima at Ladeira da Misericórdia, respond not only to aesthetic issues, but also to technical and strategic ones. They are linked to the knowledge that Bo Bardi had about the role that architecture can play both within the city and in citizens’ lives. Unfortunately, this kind of knowledge was not considered for the interventions we have mentioned here in Salvador. I believe that there is a lack of delicacy in these interventions, that neither properly conserve the existing buildings nor propose quality insertions. Both issues are needed to keep the buildings alive, which was an essential matter for Bo Bardi.

NVA: Yes, the intervention carried out by the Municipality of Salvador at the Casa do Benin is definitely arguable, but at least it allows tourists and natives to visit the Casa.

However, Bo Bardi’s works at the Ladeira da Misericordia complex are in a dire state. Restaurante do Coaty, arguably her masterpiece in Salvador, has been closed for several years and, as a result, it is deteriorating. Next door “ruin of the three arches,” as Lina called it, has serious infiltration problems, while the other three properties are barely used. Access to the Ladeira has even been forbidden by the Municipality, which blocked it off with gates after having turned it the exit route for its adjacent offices. The last time when it was possible to visit those works without special permission was two years ago, thanks to an installation created by artist Joãozito.

This also demonstrates the Municipality of Salvador’s lack of recognition of Lina Bo Bardi, particularly when considering her own architecture from a worldwide perspective, despite the relevance of the Ladeira da Misericordia among the Italian-Brazilian architect’s works.

Giacomo Pirazzoli teaches architectural design at DiDA-Department of Architecture, University of Florence, Italy. He is a 2017–2019 CAPES recipient at FAU-UPM School of Architecture, Mackenzie University, San Paulo, Brazil.

Ana Carolina Bierrenbach teaches architectural design at FAU-UFBA, School of Architecture, Bahia Federal University, Brazil. She is a member of DoCoMoMo-Bahia.

Nivaldo Vieira de Andrade Junior teaches architectural design at FAU-UFBA, School of Architecture, Bahia Federal University, Brazil. He is the president of IAB-Brazilian Institute of Architects.

The article is available in Italian in Il Giornale dell’Architettura.