A show now up at New York City’s New Museum has invited a collection of artists to probe the fluid nature of transgender history (or hirstory, a portmanteau using the gender-neutral pronoun “hir”), and the role of monuments in America today. Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project, organized by artist Chris E. Vargas and the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art (MOTHA), challenges how public monuments, even LGBTQ-oriented ones, can exclude or diminish the contributions of not only trans people, but of large and complex communities more generally. Rather than putting forward one design for a trans-oriented Stonewall memorial, the show invited a range of artists to propose monuments that would grow and evolve over time.

This amorphous approach is a reaction to the concretization of transgender history as trans communities become more widely accepted in the U.S. In June of 2016, President Obama made the Stonewall Inn in New York City a National Monument, the first to specifically highlight the LGBTQ community. The Inn was the site of the 1969 Stonewall Riots, when a group of patrons at the bar fought back against a police raid on the establishment and demanded to be treated with respect. The riots are frequently cited as the beginning of the LGBTQ rights movement in the U.S.

An existing memorial of the riots, the Gay Liberation Monument, sits in the park opposite the inn, but it, along with other public remembrances of the riots, have been accused of remembering only the roles of white, cisgender people in the LGBTQ rights movement and forgetting the role that trans women of color had in leading the riots. This perceived history of exclusion is part of what spurred Vargas to solicit a kaleidoscopic range of ideas.

“Constructing one single monument is an inadequate way to represent this history,” Vargas said. “There are so many queer subjectivities that have a stake in this.” In the New Museum show, 13 different artists have contributed their ideas for a Stonewall monument, all of which are represented in a site model of Christopher Park in the center of the gallery.

The proposals at the New Museum are all a far cry from the politely-posed statues of the Gay Liberation Monument. Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt designed gleaming rodents to remember the riots, “that night the ‘gutter rats’ shone like the brightest gold.” Nicki Green put forth a pile of bricks, both a humble building material and the weapon thrown by Stonewall rioters at the police. Jibz Cameron imagined various scenes: dancing feet, the Stonewall’s notoriously dysfunctional toilet, and a “stiletto heel being slammed into the eye of a cop.” Chris Bogia opted for an abstracted facade filled with color and dangling with pearls, saying: “I want to make something that reminds every passerby that there was a riot in this place for LOVE and that it was full of color, and that we won.”

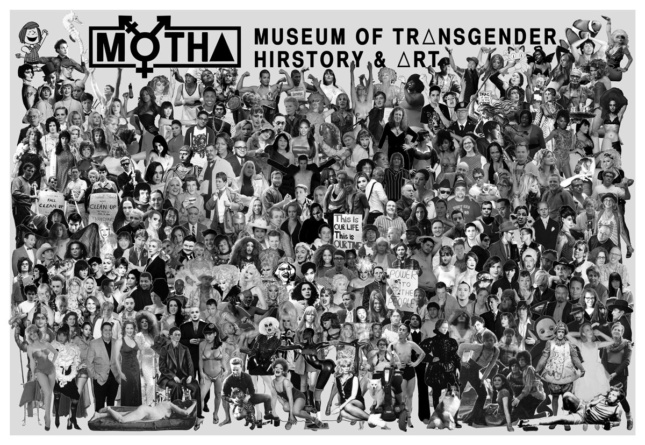

Vargas started MOTHA in 2013 as trans celebrities, like Laverne Cox, Janet Mock, and Caitlyn Jenner started to rise to national prominence. While a new era of trans visibility appeared to be dawning, Vargas noted that not everybody was getting included in the uplift: “It didn’t universally make things better in the trans community.” The visibility also began to harden some definitions, taking a range of identities, some of which had been purposefully vague, and standardizing them for a mass audience.

MOTHA was a riposte to the notion that there could be any stable definition of what it meant to be trans and that certain trans people were more worthy of visibility than others. The conceptual museum was intentionally tongue-in-cheek, as much of a lampooning of the self-seriousness and strictures of genteel art institutions as a celebration of the diversity and range of queer culture. The campy institutional critique falls in the vein of the Guerrilla Girls, the feminist activist artists who for decades have used surreal imagery and savvy design to point out the discrepancies between how art institutions treat men and women.

MOTHA’s mission statement drives its campy sensibilities home:

The Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art (MOTHA) is dedicated to moving the hirstory and art of transgender people to the center of public life. The Museum insists on an expansive and unstable definition of transgender, one that is able to encompass all transgender and gender-nonconforming art and artists. MOTHA is committed to developing a robust exhibition and programming schedule that will enrich the transgender mythos by exhibiting works by living artists and honoring the hiroes and transcestors who have come before. Despite being forever under construction, MOTHA is already the preeminent institution of its kind.

The artists participating in The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project take MOTHA’s subversive wit into the contemporary political climate, one in which trans communities are again both under attack and fighting back.

President Trump recently announced that he is considering reversing rules protecting the 1.4 million Americans who identify as transgender, while at the same time a historic amount of LGBTQ candidates are running for office and are poised to hold greater political power. Trans entertainers and performers are achieving recognition even as transgender people in the U.S. are being killed in record numbers. “There were always limitations in accepting and inclusion,” Vargas said. “This political moment has highlighted the limitations.”

Monuments have become a particular flashpoint in the U.S.’s fraught political climate, and Vargas says that he began the Stonewall project questioning the role of monuments. “I went into it with a real critical lens, but to be honest, I’ve become more understanding of the importance they play…There’s a way they can evolve over time.” Vargas cited the influence of the work of the artist Isa Genzken, whose Ground Zero sculpture series imagined for the World Trade Center site in New York City a series of kaleidoscopic churches and discos instead of drab office towers. Like Genzken’s sculptures, the Stonewall proposals embrace messy emotionality and exuberant vitality over orderly construction.

The carnivalesque approach reflects the overall strategy for MOTHA, a roving institution that Vargas says will never have a permanent physical home. “At the heart of my approach to this project is an acknowledgment that once you start you canonizing, once you start making an official history, you have to start policing boundaries of what is or isn’t considered transgender, and I don’t think the identity category lends itself to that approach.” Vargas added, “I don’t think it makes sense to have a traditional institution…It makes sense to have it exist as an evolving parasitic entity.” Which is not to say that Vargas wouldn’t want architects to imagine what a home for MOTHA could look like. “It’s been a dream of mine to have an architectural design competition for the institution,” Vargas said. Architects, take note.

Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project will be on view at the New Museum in New York City through February 3, 2019.