The history of modern architecture is filled with the efforts of architects responding to germ theory: sanitariums, hospitals, apartments for TB survivors. It was a dirty world and the early 20th century modernists were going to sanitize it through design with plenty of light and air and molding-free walls. Even burger joints and gas stations were covered in glossy white tile to signal safety and sanitation. But the curators of the latest exhibition at Storefront for Art and Architecture, Subculture: Microbial Metrics and the Multi-Species City, position their show as a corrective to all this germ anxiety by proposing we not eradicate our microbes but explore them as a force for design innovation.

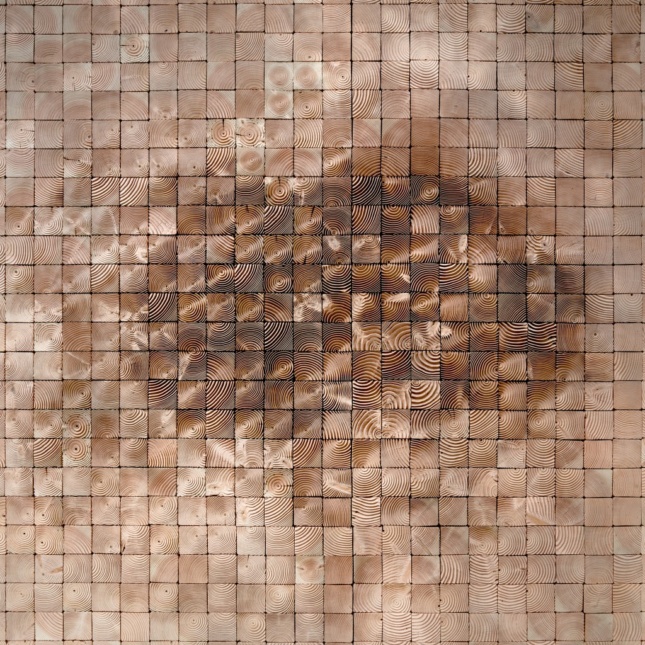

The show, which runs until January 12, finds Storefront as both a subject of study and a laboratory. The curators—Kevin Slavin, Elizabeth Hénaff, and The Living, a firm headed by David Benjamin—have set out to study locations around in New York by capturing microbes and sequencing their DNA. The team’s method is elegantly simple: by sandblasting wooden blocks to various depths, they’ve created a set of porous tiles filled with crevices for microbial life to accumulate. Not coincidentally, the tiles, as arranged on Storefront’s facade, also have an aesthetic dimension, making patterns that from a distance, recall smudged fingerprints, old-school identity markers.

And that’s suiting since the real star of Subculture isn’t so much the microbes themselves as the human ability to identify them using DNA sequencing. Accordingly, the exhibition is divided into three parts: Models, Metrics, and Maps. The first lays out the rationale of the exhibition: Today there are multiple ways that architects and builders set out to ensure a clean environment. But, the show asks, what exactly are we getting rid of? Since life on earth is 90 percent invisible to the human eye, we can use the newest tools available to learn more about the microscopic stew we’re unwittingly steeped in. To that end, the Metrics section has been set up in Storefront’s exhibition space to provide what the exhibition text calls a “working laboratory that features the equipment and processes used in metagenomic experiment.” What’s on view isn’t half that exciting—there are pipettes, a DNA sequencer, and a wall-mounted device that types out the sequence of genetic proteins, a sort of teletype for the invisible. But of course, the point is that the action is exactly what we can’t see.

Not surprisingly, the curators all are alumni of the MIT Media Lab where there have been numerous projects using gene sequencing to understand the microscopic level of the environment. While at MIT, Slavin spearheaded a somewhat similar project in which data was collected from beehives around the world. The Living investigates biological systems for their architectural potential. In 2014, the firm won MoMA PS 1’s Young Architects Program by growing a 14-foot tower out of bricks they made from refuse: corn stalks, mycelium spores, and root structures. And Hénaff has examined microbial life in locations from the Gowanus Canal to Penn Station, that last as a post-doc in the Cornell lab that produced a 2015 report on subway microbiomes. It revealed among other pathogens, the presence of bubonic plague, a fact that was met with only a slight dent to the usual New Yorker sangfroid.

Some visitors to the show seemed to agree that we have been sanitizing ourselves to death. “I mean, we use all these HEPA filters!” said one man, though one wonders what he’d make of the current rash of Legionnaires’ disease in the Bronx resulting from dirty water towers. The show isn’t calling for the end of all sanitary precautions, but the curators’ idea that we are “undermining the importance and actual presence of legitimate bacterial diversity in our urban lives” may be a stretch in an era when so many people lack even those basic protections.

Yet with the unfolding catastrophe engendered by the bigger-is-better ethos, it seems natural that we should be turning our collective lens to the microscopic. The show implies that the destruction of microbial matter is a form of spatial isolation—one that hasn’t served us well. It’s a powerful thesis that opens extraordinary possibilities for design.

But their position will be a tough sell: On a recent evening outside of Storefront, a woman ran her hands along the whorls of the wooden tiles, then rummaged through her backpack for a tube of hand sanitizer. After slathering herself in the stuff, she offered some to a friend: “It’s getting to be flu season.”