Ed Mitchell began his role as the new director of the University of Cincinnati‘s School of Architecture and Interior Design (SAID) one year ago. Notable for its innovative century-old cooperative education platform, the school’s rankings have dipped in the past decades out of the country’s elite programs. In this interview, Mitchell—whose resume includes an energetic mix of professional practice and academic positions at Columbia, Pratt, Yale, IIT, and more—explains his vision for the school and the move from the east coast to the midwest.

The Architect’s Newspaper: At the time you took the role of SAID director, you were in charge of the post-professional program at Yale and an Associate Professor there.

Ed Mitchell: There were things we were doing in studios at Yale that I thought had the mission of a “school.” What I liked about the students at Yale—especially the post-professional students—was that they were international. Their perspective on issues was very different from the standard American East Coast background that Yale typically gets. We were doing studios where the problem was wide open—but it was real.

It wasn’t a problem of program or constructional limitations. What was important was a real evaluation of the aesthetics and formal control of architecture to other disciplines. There were physical aspects of city-making that compelled me.

People would come to both of us with questions like: “We’ve got 1,600 acres. What should we do? We need an answer in three weeks.” That was the problem.

As a result, our students would get involved in the actual project—meet with state officials, local politicians, developers, fishermen, industry workers, local immigrant communities—and actually stage the city they wanted to have happen.

AN: Why did you apply for the job in Cincinnati?

EM: Cincinnati, if you’ve never come out here, is an exotic place. Everything was new here for me. It was like being in a foreign country. As an architect, this is one of the most beautiful architectural cities I’ve been too, bar (almost) none.

Cincinnati is the westernmost eastern city, the southernmost northern city, and the northernmost southern city in the country. Nothing is resolved here! The city has an incredible history that you feel around you all the time. This is the subculture that makes a place interesting. It’s the kind of place that I always gravitated to—I lived in Providence as an undergraduate. I moved to New York and San Francisco in the ’80’s which were both like that. If you were talented and had energy, then people would find out about you, and they might just invite you to collaborate with them. It wasn’t like you had to pay dues to gain access.

What’s interesting about a city like Cincinnati is that it’s relatively easy to get into the community to do work. The cost of the education is relatively low—when high tuition cost prohibits at a point of entry from certain economic classes that isn’t right. If you are eliminating talent based on income, you’re not doing anything important anymore. This was the right school with the right kind of potential.

AN: What are you most excited about in your new position as director of SAID?

EM: $2 beers and cheap bowling. An exciting art scene of young people in the city. Adjunct faculty who looked like they might have the kind of energy to take this to the next level. I sensed people wanted somebody to push the energy level up—to keep it up and stay positive about it.

A lot of people forgot about the University of Cincinnati. On the east coast, it had a reputation as a great school. The midwestern schools safeguarded and championed the discipline of architecture for several decades. I still think of it that way, but admittedly many students are not familiar with the place and its mission.

People are a little intimidated about taking risks, and this might be a risky place to be. It’s not New York or L.A. or London. But it’s a place where culture arises from.

You have opportunities here that you wouldn’t have elsewhere. This week was incredible. The first year graduate studio built a pavilion on the main campus in two and a half weeks that’s pretty incredible; we have five books coming out next month after one year. We have a new dean incoming from Hong Kong who is bringing a global perspective to the college.

AN: What plans do you have for the school? What’s your vision for it?

EM: A lot of people don’t realize Cincinnati has a 100-year old co-op program where a portion of the curriculum is dedicated to students working in offices around the world.

The idea of the cooperative was a radical political agenda in the midwest. It would be an exciting mission for the school to take it dead seriously. Not just as a service to professional offices—there’s nothing wrong with that—but what the cooperative project really is.

Whether that’s questioning our urban futures, or taking a group of new students and in three weeks building a community structure to host events, or organizing the junior faculty in a three-city exhibition. There’s an attitude here: an “all hands on deck” approach. Everyone pitches in to get things accomplished. I think this is fantastic—something you don’t get in a lot of places. People here are competitive and want to do excellent work, but they’re supportive and cooperative towards a larger cultural effort.

AN: Explain the issues facing the school.

EM: The school’s reputation was in the accredited B.Arch program. I think we need to define what a Masters program is. The real question is what do we do different here than other schools? It’s a relatively small program in size with a “down home” work ethic about what it does. However, that shouldn’t stop it from being creative and original. Ohio is full of great subcultures in the arts and music from its utopian past to the birth of punk in Cleveland and Akron. We need to keep that spirit in architecture.

There’s too much focus on program and not enough critique of architecture. The good intentions of the students and faculty sometimes backfire: the moral is a way of dodging the physique.

Some of our students travel internationally through co-op, but historically we haven’t had strong enough partnerships with international academic programs. For example, our students will work in Beijing on a co-op, but they haven’t actually done studio work there or looked at larger international problems that they’ll probably be involved in within offices. So I’m trying to find a way that we can do research-based work within the school. Not only as a studio imperative but as an extended research project in a developing post-doc program or the existing doctoral programs. These projects can become longer-term sustained revisitation of a series of problems. In this way, international studies become less episodic and more engaged with a broader mission statement.

AN: Since you were at Eisenman’s office in the mid-’90s during the design of the school addition, what insights can you share about the building? Can you tell us how it operates?

EM: The building has a legacy as one of the last buildings during the peak of a critical, theoretical approach in formalism. When I got out of school, I thought this was the only thing architecture would be left to do. It’s an important legacy to retain, but not one to continually emulate to the point of exhaustion.

It’s like a medieval city—you have to learn it’s internal routes. There are ways of moving about the building that inspire conspiracies, gang organizations, and new collectives.

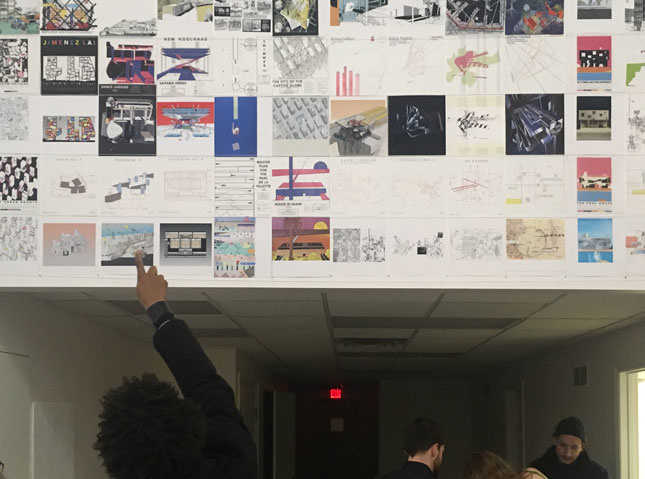

The main space in the building exists as a great gallery of work. SAID tends to occupy this space as much as it can. You can sit there, eat a sandwich, roll around on the floor, look at your work. People are in discussions there. It’s a really active space and didactive for our students and faculty.

AN: While SAID is one of four broader schools within DAAP, it contains two disciplines: architecture and interior design. Culturally, these programs feel like two different worlds, each with their own academic agendas and representational toolsets.

EM: I’d like for the two disciplines to interplay more. There are things that each does better. Something is fascinating about how, in the 18th century, things like color couldn’t be described scientifically. Issues like color and shape that weren’t normative or relative to a platonic solid fell out of the discourse of architecture because they couldn’t be documented, written, and transcribed. Interiors, as a discipline, didn’t really emerge until the 19th century when “identity” became an issue. This led to a wide range of proto-formations of architecture and spatial matrices. Cincinnati is full of that because it emerged as a great city during this time of a shifting cultural spectrum. The result is that it’s a place where you can invent stuff—there is great high modernism here, there’s incredible Victorian architecture, and the landscape and river have its own unique presence. I think you can tap into that variety of circumstances, ecologies, and histories.