Every year the Architectural League of New York recognizes eight dynamic young firms as Emerging Voices that have the potential to become leaders in the field. Historic winners like Morphosis (1983) and Toshiko Mori (1992) have become today’s lions, and practices like Johnston Marklee (2007) and Tatiana Bilbao (2010) have jumped to new heights after recent wins.

This year’s crop was selected in a two-stage portfolio competition where a jury of architects selected the winners. The deciding jury included several previous winners like Dominic Leong (2017), Fernanda Canales (2018), and Marlon Blackwell (1998), giving the process a familial feel. Laureates for 2019 come from across North America and almost all are partnerships or collaboratives—capital letters feature prominently, too.

Colloqate will lecture at the Scholastic Auditorium at 130 Mercer Street, New York, New York, at 7:00 p.m. on March 28, as part of the Emerging Voices lecture series.

Colloqate Design, a multidisciplinary, New Orleans–based “nonprofit design justice practice” founded in 2017 by Bryan Lee Jr.—Sue Mobley came on in 2018—with the goal of “building power through the design of public, civic, and cultural spaces,” is setting a different path relative to other design offices.

For one, Colloqate spends quite a bit of time doing the arduous work of educating and training communities, institutions, and municipal agencies through initiatives like its Design as Protest and Design Justice Summit events to “build practices around design justice,” according to Lee. Buildings are not an afterthought for the practice, but Lee and Mobley’s view of how designers and design justice intersect is firmly rooted in grappling with everything that exists beyond and around their particular projects.

According to the duo, this “syntax of built environment”—including but not limited to the social mores we keep, the design of streetscapes and infrastructure, and the impact of political policies—has as direct an impact on how people use spaces as any one design element might. So a key goal of their practice involves making others aware of how these overlapping and sometimes competing languages operate so that when they do building-oriented design work in a given space, they can “intentionally organize, advocate, and design spaces of racial, social, and cultural equity.”

The practice started off as an outgrowth of the Claiborne Corridor Cultural Innovation District, a visionary urban plan that would transform a 19-block area below an elevated highway in New Orleans into a “culture-based economic driver” for the Claiborne Corridor neighborhood. The plan, envisioned for an area that was once a social and economic core of New Orleans’s black community but was cleared to make room for the highway, aims to articulate a socially guided vision for bringing a public market, classrooms, exhibition spaces, and health, environmental, and social services to the area.

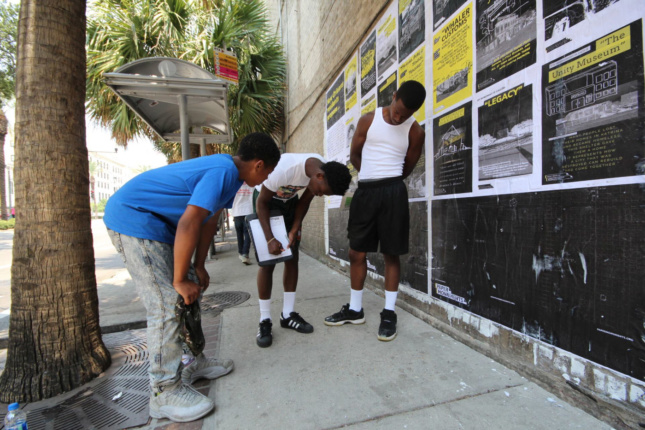

Another project, Paper Monuments, brought a flurry of posters to sites across the city to “create new narratives and symbols of [New Orleans]…and to honor the erased histories of the people, events, movements, and places that have made up the past three hundred years” of history. The citizen-led project sought to use public art as a way to further Colloqate’s core aim of “dismantling the privilege and power structures that use the design professions to maintain systems of injustice.”

Lee explained that as a nonprofit entity (Colloqate’s growing board includes urban planners, architects, and other design professionals), Colloqate must necessarily take an unorthodox and provocative approach. As the practice expands, completes projects, and envisions its future, however, Lee hopes to apply Colloqate’s ethos more directly to bricks and mortar. “We want to be the most radical design firm out there,” Lee said, “and we need to build buildings to do that.”