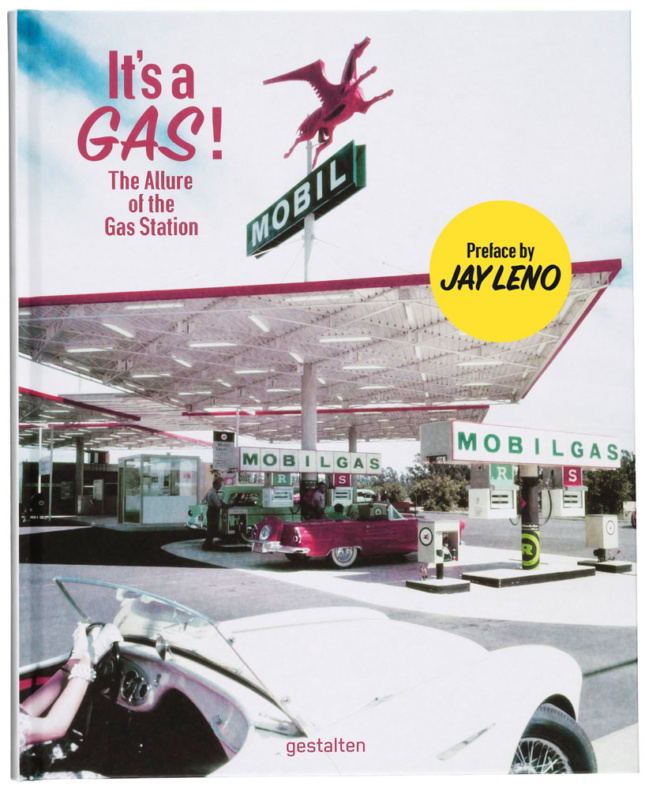

It’s a Gas: The Allure of the Gas Station

Edited by Sascha Friesike, with a preface by Jay Leno

Gestalten

$60.00

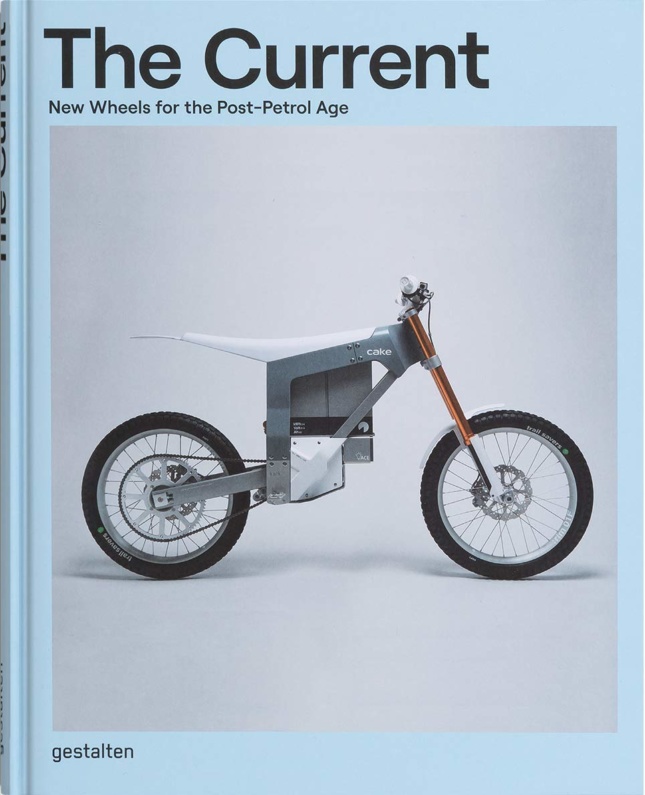

The Current: New Wheels for the Post-Petrol Age

By Paul d’Orléans, Robert Klanten, and Maximilian Funk

Gestalten

$50.00

Automobiles fascinate architects. Le Corbusier designed the Voiture Minimum; Buckminster Fuller, the Dymaxion; Renzo Piano, the Flying Carpet; and Norman Foster, the Routemaste. And while Charles and Ray Eames were posing with a Velocette motorcycle, Michael Czysz—founder of Architropolis, his firm—was designing the record-breaking MotoCzysz E1pc electric motorcycle. Given recent developments in electric vehicle (EV) innovations, designers may soon create new infrastructure for these silent, zero-emission vehicles. Two books from international publishing house Gestalten reflect on this crossroads with one foot on the accelerator and one hand on the wheel.

Jay Leno—late-night comedian and automobile aficionado—introduces It’s a Gas: The Allure of the Gas Station, edited by Sascha Friesike. Leno recalls his childhood fascination with “grease monkeys,” tending vehicles, hot rods, and watching new models come and go. Leno also remarks on gas station architecture, including Richard Neutra’s now-demolished stations. From the introduction onward, Friesike’s volume takes us on a joyride around the world of gas stations.

Gas stations never became a celebrated typology, despite celebrated architects like Albert Frey and Norman Foster designing them. It’s a Gas begins to address this curiosity. Friesike presents an aesthetic history of the gas station from its 1888 origins in a Wieshold, Germany, pharmacy to the contemporary designs of Philippe Samyn and Partners. Along the way, Friesike also casts his gaze on Arne Jacobsen’s 1936 rectilinear facility with a contrasting sinuous canopy—a beautiful prototype sadly never replicated—and Atelier SAD’s mushroom column canopy.

Canopies are typological features that shield from sleet, sun, and rain, and can encompass concrete shells, decked trusses, or even a B-17 bomber. Some stations forgo the billboard and inhabit teapots, tee-pees, and cowboy hats. Novelty attracts customers (there even exist floating gas stations to service motorboats), but unfortunately, in the U.S., mega-pump filling stations like Buc-ees seem to pass for novel. Canopies can differ greatly. Postcards from Eugenio Grosso’s trek from Kurdistan to Sulaymaniyah, and Tim Hölscher’s photos of isolated gas pumps and stations highlight typological differences.

Every modern master has had stops and starts in petroland. In Quebec, in 2011 (the book misdates it as 2002), Les Architectes FABG completed the conversion of Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie-esque gas station into a community center. In 2014, the Pierce-Arrow Museum in Buffalo, New York, unveiled a non-operational version of Frank Lloyd Wright’s never-realized station. Equal parts nostalgia and premonition, “Ghost Town Gas Stations” closes It’s a Gas by questioning the gas station’s future. If their fall “from grace came as the golden age of flying was ushered in,” will they hit rock bottom now that EVs have hit the scene?

The Current: New Wheels for the Post-Petrol Age by Paul d’Orléans, Robert Klanten, and Maximilian Funk leans into this question, examining the state of EVs. Motorcycle aficionado d’Orléans charges through a history of EVs before running the gamut of the latest electric transporters. Given the author’s focus on motorcycle history and customization (and from working with him personally at motorcycle film festivals), I was pleasantly surprised to see all manner of land vehicles included in his survey.

EVs are ideal for urban commuting. Electronic cars and motorcycles have a range of 150 miles at highway speeds. Electric bicycles and scooters are more accessible, but fizzle out around 60-mile ranges at 35 mph. China has been leading this “e-volution” by changing licensing classifications on e-scooters and banning internal combustion engine (ICE) scooters in large cities, leading to myriad manufacturers and sales of e-scooters. Other countries have been slower to adopt EVs, despite riders’ praise of their “fun factor” and sustainability.

To combat customer hesitation, Taiwan-based electric scooter manufacturer Gogoro designed an e-scooter with batteries that can be easily exchanged. A subscription-based station network in Taipei supports its riders, who have already collectively logged 186 million miles. This infrastructure is key to reassuring potential riders that their destinations can be reached. Similar networks are now being planned for Paris and Berlin.

Even mainstream manufacturers are flipping the switch. BMW developed an e-motorcycle weighing in at 600 pounds—a whale by industry standards, as many other models hover at around 250 pounds. Other large manufacturers developing EVs on the two- and four-wheel front include KTM, Yamaha, Porsche, Lamborghini, and Honda. Tackling a more sustainable approach, Ferrari has developed an E-Type concept retrofit for its 1950s through ’70s models. Taking sustainability further, the Dutch e-scooter Be.e boasts a flax and bio-resin body that foregoes the use of metal and carbon. Waarmaker—the designers of the scooter—said of their design process: “Form follows material and production.”

Many EVs don’t travel far from the traditional styling of their ICE cousins. D’Orléans explains: “Designers walk a fine line of trying to push the boundaries of styling and technology while catering to a surprisingly conservative streak among the supposed rebels on two wheels.” The same goes for cars—witness name-brand dealer offerings. Thankfully, d’Orléans’s arc surpasses workaday solutions to showcase more provocative and lesser-known innovators.

Joey Ruiter, who has designed furniture for Herman Miller, eschewed telltale signs in his Consumer car and Moto Undone motorcycle: Both are pared-down, minimal, rectilinear forms, in black and mirror finishes, respectively. These vehicles, while alluring, do not reference any stereotypical automotive styling. Bandit9 Motors’ bespoke L-Concept motorcycle is a tube with a turbine attached on two wheels. Meanwhile, Ujet’s Electric Scooter looks traditional but has an asymmetrical folding frame and battery-seat module that can be detached like a portable, wheeled tote for easy recharging. BMW’s Motorrad VISION NEXT 100 concept vehicle at once mimics the lines of the company’s first motorcycle and resembles a Tron Light Cycle. United Nude’s black crystalline Lo Res Car is as mysterious as Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey monolith. EVs and their potential infrastructures are inherently sci-fi.

The books by Friesike and d’Orléans are both beautifully designed and illustrated, and one won’t find better volumes on EVs and gas stations without traveling to the realm of the overly technical. The Current lists specifications with its case studies, but highlights design, not mechanics. It’s a Gas exposes a new typology without drilling into the industry. Together these books anticipate the future of automobile architecture, including approaches to designing adaptive reuses of filling stations and exploring new types of e-stations.