For many of the people opposed to Amazon establishing a second headquarters (HQ2) in Queens, New York, casting the company into total exile was never the point. At its heart, opposition lay with the terms of the deal that wooed the company—its massive tax incentives, the process that had created the deal (without input or oversight from the New York City Council or local communities), and the dramatic impact such a real estate development project would have on the city’s working class, especially by aggravating its gentrification and displacement crises.

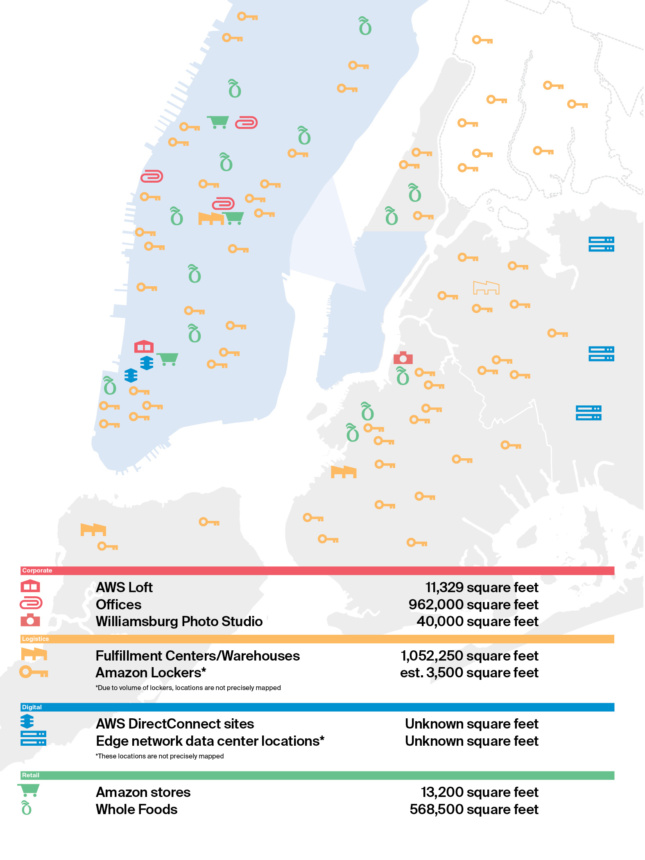

Facing a groundswell of local opposition, Amazon announced that it had canceled its plans for a new Queens campus on February 14, just three months after announcing its selection. While HQ2’s optics and scale made it a legible enemy to rally against, Amazon’s less splashy development projects have already become part of the fabric of many cities, including New York. Taking inventory of Amazon’s existing physical footprint in the city, one begins to perceive a shadow infrastructure at work which reshapes urban environments more through privatized logistics and information systems than through campus construction.

In Manhattan, Amazon’s physical presence might best be recognized in retail. It was at the company’s 34th Street bookstore that protestors demonstrated on Cyber Monday following the HQ2 announcement. Indeed, like HQ2, the company’s retail stores serve as useful rallying points. But inside the same Midtown Manhattan building that hosts the bookstore sits a more explicit locus of Amazon’s presence: a 50,000-square-foot warehouse and distribution center for the company’s Prime Now delivery service.

It might be helpful to state here what Amazon actually is: a logistics company misrepresented as a retail company misrepresented as a tech company. Over time, the types of products the company sells have expanded beyond books and bassinets into less obviously tangible commodities like data (via Amazon Web Services), labor (via Amazon Mechanical Turk), and “content” (via Twitch and Amazon Studios productions).

Ultimately the company’s appeal isn’t so much in the stuff it provides but the efficiency with which it provides stuff. Computation is obviously an important part of running a logistics operation, but Amazon’s logistical ends are frequently obscured by the hype around its technical prowess. And while Amazon is increasingly in the game of making actual things, a lot of them are commodities that, in the long run, enable the movement of other commodities: Amazon Echos aren’t just nice speakers, they’re a means of streamlining the online shopping experience into verbal commands and gathering hundreds of thousands of data points. Producing award-winning films and TV shows gives the company a patina of cultural respectability, but streaming them on Amazon Prime gets more people on Amazon and, in theory, buying things using Amazon Prime accounts.

Amazon’s logistical foundation is most blatantly visible in the company’s nearly 900 warehouses located around the world. Currently, the company has one fulfillment center (FC) in New York City. The 855,000-square-foot site in Staten Island opened in fall 2018 and had already earned Amazon $18 million in tax credits from the state of New York before the HQ2 deal was announced. Additionally, a month before the HQ2 announcement, Amazon had also signed a ten-year lease for a new fulfillment center in Woodside, Queens.

The same day that Amazon vice president Brian Huseman testified before the New York City Council about HQ2, Staten Island warehouse employees and organizers from the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU) announced a plan to form a union at the Staten Island FC, citing exhausting and unsafe working conditions better optimized for warehouse robots than employees. These conditions are far from unique to Staten Island—stories about the grueling pace, unhealthy environment, and precarity of contract workers at fulfillment centers have been reported regularly as far back as 2011.

And yet, when the Staten Island FC was first announced in 2017, a small handful of media outlets made note of this record. Unions and community leaders weren’t galvanized against the Staten island FC the way they were by HQ2 or the way they had been when Wal-Mart attempted to come to New York in 2011. In some ways, the HQ2 debacle gave new life and momentum to an organized labor challenge previously hidden in plain sight (or at least in the outer boroughs).

Of course, Amazon’s logistics spaces aren’t solely confined to far-flung corners of the New York metro area: There are two Prime Now distribution hubs in New York, one in Brooklyn and the other at the previously mentioned Midtown Manhattan location. Same-day delivery service Prime Now originated from that Midtown warehouse in 2014 and spawned Amazon Flex, an app-based platform for freelance delivery drivers to distribute Prime Now packages. (Ironically, one of the reasons Amazon has been able to become so effectively entrenched in the city is because of this kind of contingent labor force—any car in New York City can become an Amazon Flex delivery vehicle, any apartment a Mechanical Turker workplace.)

The art of logistics also depends in part on the art of marketing. To support that marketing endeavor, Amazon has a 40,000-square-foot photo studio in a former glass manufacturing plant in Williamsburg that produces tens of thousands of images for Amazon Fashion, the company’s online apparel venture. The company’s forays into fashion, while less publicized, may also position it to become one of the largest retailers of clothing in the world.

New York is also home to 260 Amazon Lockers: pickup and package return sites for select products typically located in 7-Elevens and other bodega-like environments. Like Prime Now, the Lockers streamline and automate a process that would normally involve lines at the post office. First appearing in New York in 2011, the 6-foot-tall locker units can range between 6 and 15 feet wide, with the individual lockers in each unit capable of holding packages no larger than 19 x 12 x 14 inches (roughly larger than a shoebox).

While early reports indicated that store owners received a small monthly stipend for hosting the lockers, the main sell for store owners is the possibility of luring in more foot traffic. But a 2013 Bloomberg article noted that smaller businesses were frustrated by the limited returns from installing the lockers and increased power bills (lockers use a digital passcode system, requiring electricity and connectivity). There is an irony in the fact that for almost a decade before the HQ2 debacle, small businesses have been ceding physical space to Amazon only to be stuck with monolithic storage spaces serving little direct benefit.

Following its acquisition of Whole Foods in 2017, Amazon installed Lockers in all of the supermarket’s locations in the city. Whole Foods was already associated with gentrification and had an anti-union CEO before the Amazon acquisition; if anything, Amazon upped the ante by attempting to bring Whole Foods more in line with Amazon’s logistics-first approach.

Reports that Amazon has plans to open a new grocery chain suggest that early speculation about the Whole Foods acquisition was correct: Amazon wasn’t interested in Whole Foods in order to sell produce so much as to gain access to the grocery company’s rich trove of retail data, which Amazon could use to jump-start its own grocery operations. A data-driven approach has been at the core of Amazon’s logistics empire: The company was one of the first to use recommendation algorithms to show consumers other products they might also like, and Prime Now relies extensively on purchasing data to determine what items to stock in hub warehouses.

It’s unsurprising, then, that the most profitable wing of Amazon’s empire is Amazon Web Services (AWS), its cloud computing platform. AWS’s physical footprint in New York City is relatively small, with a handful of data centers within city limits. Its most visible presence may be the AWS Loft in Soho, which opened in 2015, part of a small network of similar spots in San Francisco, Tokyo, Johannesburg, and Tel Aviv. Part coworking space for startups that use AWS and part training center for AWS products and services, the Loft inhabits a kind of in-between space between data services and marketing. The space is free for AWS users and is full of comfy seating and amenities like free coffee and snacks—ironic considering Amazon’s reputation for being absent of the kinds of perks expected at tech companies.

Belying its small spatial footprint, AWS is a major part of the city’s networked operations. The New York City Department of Transportation and the New York Public Library are both presented as model case studies of successful AWS customers, and AWS has signed contracts with multiple city agencies, including the Departments of Education and Sanitation and the City Council as far back as 2014. AWS is also a major vendor to municipal, state, and federal agencies—and, increasingly, has come under scrutiny for its multimillion-dollar contracts with data mining company Palantir Technologies, which works with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to track and deport migrants, and for peddling its face recognition technology to police departments across the country.

Some of the criticism of Amazon’s campus deal with NYC came from New York City Council members, apparently unaware their office was paying Amazon for hosting web support. To be fair, New York City’s AWS contracts (including the City Council’s) are a fraction of the kind of revenue Amazon is vying for in federal defense contracts. And at this point, AWS is the industry standard upon which most of the internet runs. The situation reflects the depth to which Amazon has insinuated itself as a fundamental infrastructure provider.

New York may have dodged a gentrification bullet with HQ2, but as with so much of Big Tech, Amazon’s impact on cities might look more like death by a thousand paper cuts. A new campus might be more visible than the hidden machinery of a city increasingly reliant on delivery-based services, but both impact local economies, residents, and living conditions. Amazon’s long-standing logistics regime also inspires an infinitude of Amazon-inspired niche delivery startups familiar to New Yorkers as a pastel monoscape of subway ads hawking mattresses, house cleaning services, and roommates, to name just a few, along with the precarious jobs that are their defining characteristic.

There have been continued efforts in New York to challenge Amazon’s frictionless logistics regime since the HQ2 withdrawal. Pending City Council legislation banning cashless retail would affect far more businesses than just Amazon’s brick-and-mortar operations (which have automatic app-based checkout), but it would certainly stymie any expansion of its physical retail footprint. State Senator Jessica Ramos has joined labor leaders in calling for a fair union vote at the future Woodside fulfillment center. These sorts of initiatives are often more drawn out and less galvanizing than those to halt a major campus development. But they’re crucial to a larger strategy for making the tech-enabled systems of inequality in cities visible.

In 2019, the premise that the digital and physical worlds are mysteriously separate realms has been effectively killed by the tech industry’s measurable impact on urban life, from real estate prices to energy consumption. Comprehending the full impact of companies like Amazon on cities and seeing beyond their efforts to obscure or embellish their presence (glamour shots of data centers, anyone?) requires a full examination of these infrastructures outside of the companies’ preferred terms. By demanding public accountability, New York’s elected officials and community groups may have demonstrated the beginnings of just how to do that.