On the blacked-out front door of Ludlow 38, the Goethe Institute’s downtown outpost, is a plaque. In simple, sans serif, white letters it says: “THIS GALLERY CONTAINS GRAPHIC IMAGERY. PARENT/ADULT DISCRETION IS ADVISED.” Open the door and even before you cross the threshold you’ll hear moaning. Or at least I did. I suppose timing matters—not every moment of what turns out to be Shu Lea Cheang’s 2001 video I.K.U. – I robosex has moaning. Inside, with the windows blacked out and the overhead lamps turned off, purple LED strips hidden behind walls provide the only light in the gallery, and it’s hard to make things out clearly. It hardly feels like an art exhibition but there is still a gallery attendant at the front desk, which reminds you that you do have to behave.

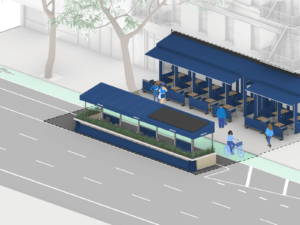

This is Cruising Pavilion, New York, the second of three iterations of the architectural exploration of gay sex and cruising originally presented to coincide with the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale and created and curated by Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault, and Charles Teyssou, and produced along with the Ludlow 38 curator, Franziska Sophie Wildförster. The third, and perhaps final, Cruising Pavilion will go up in Stockholm this fall.

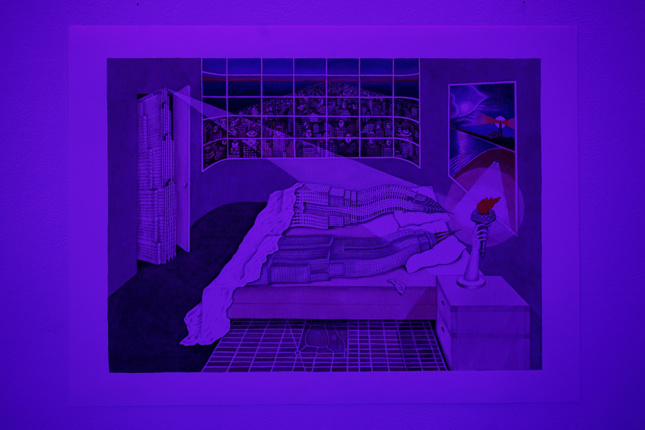

Madelon Vriesendorp, Flagrant délit (Delirious New York), 1975 (Photo by Jason Loeb/Artwork courtesy of the artist, image courtesy of Cruising Pavilion curators)

A friend and I often remark that there are no real gay bars on the east side below Delancey—or even below Houston, really—where we actually live and spend most of our time. The area is not and has never really been known as an epicenter of gay culture, the way the Village, Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen, and, as unbelievable as it may be now, Times Square have been. As far as I know, there are no regularly operating backrooms, like those you can still find in the East Village, though I’m sure there are some private spaces where people have their share of fun. Even still, those rooms-behind-the-curtain have diminished—along with the theaters, the bathhouses, and certainly the piers—all things well before my time, my time being mostly post-Grindr and long after the first rounds of the mass sanitation of New York City. The powerwashing of our streets with money and moralism continues, as if there were anything less pornographic than New York’s extravagantly boring displays of wealth. There are few things more obscene and less stimulating than the recently opened Hudson Yards. Financial hedonism rarely breeds originality, and if cash is what gets you off, it’s probably because you’re bad in bed.

Robert Getso, NYC Go-Go (Postcards from the Edge), 2014 (Photo by Jason Loeb/Artwork courtesy of Tim Landers, image courtesy of Cruising Pavilion curators)

At the opening, the exhibition did remind me a bit of moving about backrooms—bodies bouncing like so many pinballs, everything homogenizing into a swarm—but here I was less drunk and more clothed, and, of course, there was the fear, my fear, of damaging the art (some were less cautious—outside the show someone told me a bit of plexiglass had fallen victim to an errant elbow).

Inside, I saw friends, former lovers, and former one night stands. Somebody told me there were poppers in the fog machine. I’m not sure if that’s true, nor if that’s safe, but either way the impression that there could’ve been some speaks to a sense of sensuality, danger, and seediness rarely seen in architecture exhibition. Like museums and galleries, sex and chemicals promise a trip to somewhere else. Perhaps the fog should remind us of the steam of the Continental Baths, long gone, which the curators cite in their release.

Robert Yang, The Tearoom, 2017 (Photo by Jason Loeb/Courtesy of Cruising Pavilion curators)

The Cruising Pavilion highlights the historical entanglements of what the curators call “conflictual architectures.” It mines the ineluctably intertwined histories of policing, neoliberalization, right-wing moralism, homonormalization, gentrification, the AIDS crisis, and so on, to map the real past and the gaps of the present, acting as a cartography of possibilities for the queer (mis)use of space. The exhibition is a blueprint towards performances of sexual dissidence, exposing the erotic potentials lurking in hidden dark corners, or maybe even out in the open, should you only try to catch someone—or be caught—in the act. A radical reframing of the notion of “architecture,” Cruising Pavilion and the artists and architects it features interrogate sex and sexuality as a way of re- and dis-figuring buildings and cities the world over.

Cruising, beyond being a sexual practice, is a spatial one—a phenomenological perversion that uses vision and touch to establish a set of relationships not just between individuals, but between individuals and the spaces they move through. Queer space is produced by its users as much if not more so than by its owners and architects. Sexuality is not just decoration, though it is that too, but, as Cruising Pavilion proposes, sex is a constitutive act of architecture.

Ann Krsul, Amy Cappellazzo, Alexis Roworth, and Sarah Drake. Lesbian Xanadu, December 1992 (Photo by Jason Loeb/Magazine and print courtesy of the artists, image courtesy of Cruising Pavilion curators)

Museums and galleries make themselves by making rules. They regulate where bodies go, how close and how far from objects you can get, what you can and can’t touch (in general, you can’t touch much of anything). At the Cruising Pavilion it still probably isn’t advisable to touch (it is, after all, an art show) and I doubt getting it on is officially condoned. But for those compelled by the at-once exhibitionist and elusive acts of public sex or furtive hookups, isn’t breaking the rules part of the fun?

But the fog and the psychedelic lush of lights evoke another space: The club. Of course, the club, too, can be sanitized and the curators point out the “de-sexualization of disco and house music and their mutations into the official anthem of ‘happy globalization.’” The neoliberal city, like Epcot, sounds better with a soundtrack. The point of the club was and is being together, increasingly important in the AirPod era. It’s hard not to think of the recent closing of the Dreamhouse, itself a veritable ad hoc architectural carnival, home to artist studios and to Spectrum, the favorite after-hours haunt of New York City’s artists, designers, DJs—weirdos and queerdos who came together to dance and talk and screw well past sunrise. One could presumably go to the gallery on drugs, but you’d still have to watch how you acted, lest you be kicked out.

Kayode Ojo, Wassily, Interrupted (Lucas, James), 2019. Wassily chair by Marcel Breuer, Zara Woman sequined halter neck black fringed dress, clear AMAC boxes, mirror. (Photo by Jason Loeb/Artwork courtesy of the artist, image courtesy of Cruising Pavilion curators)

Perhaps the biggest queering of space is the simultaneous sensory overload and denial, the ocular S&M that plays out, at once enticing you and denying you. You can’t touch and you can’t see, but boy do you want to. This exhibition’s a tease, which is to say, it—like all art—is about desire and discipline.

Cruising Pavilion

Ludlow 38

New York, New York

Through April 7