What if instead of photographing your home to remember its significance in your life, you recreated its walls, windows, and doors by casting them in liquid latex? That’s quite the committed way of capturing the space of life, but one that could also produce a more tangible record of space.

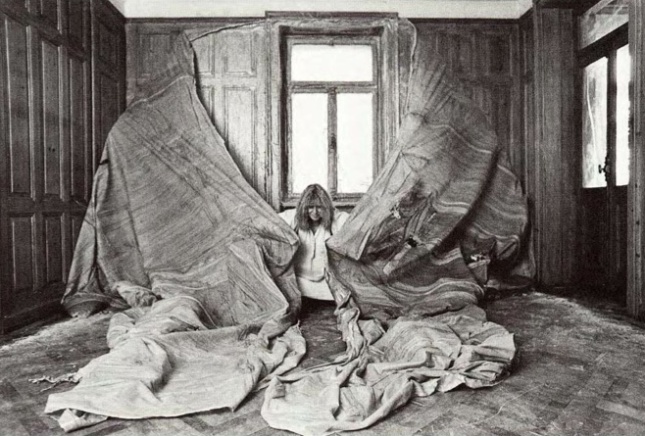

The seminal Swiss sculptor and performance artist Heidi Bucher did just that in the mid-1970s and ’80s. Late in her career, she discovered a new, experimental artform of “skinning” spaces by pressing gauze against the surface of a building or object, spreading latex on top of it, and then peeling off the cast with all her might.

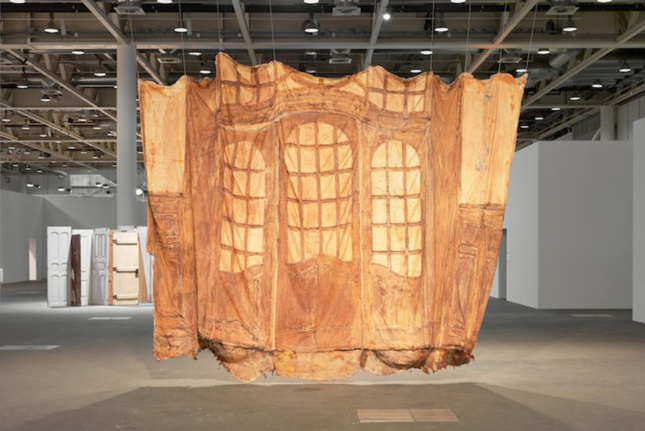

A survey of these monumental pieces, which have been pristinely kept by her family, will be on view in the new exhibition, Heidi Bucher: The Site of Memory, at the Lehmann Maupin Gallery in New York from April 29 to June 15. Viewers will be able to see up-close and personal the details and textures that Bucher was able to capture.

Featuring Bucher’s most iconic sculptures, like Borg from 1976, a piece molded on the entire cellar of her studio, the exhibition will provide insights into the artist’s intensive latex casting method and the lengths that she would go to record spaces. Also included will be works shown for the first time in the United States like Untitled (Door to the Herrenzimmer) from 1978, a sculpture that, like much of Bucher’s work, takes on an ethereal quality thanks to the mother-of-pearl she pasted over her pieces to create an iridescent sheen. Though her projects have naturally browned over time, such touches gave helped them maintain an aura of elusive depth.

“I don’t think she was trying to be super precious with these materials,” said Anna Stothart, curatorial director of Lehmann Maupin. “For her, these skins had certain layers of beauty but were also meant to express the specific personal, social, and historic memories held in these architectural spaces. You can even see the residue of the paint pulled from the surface of whatever she was casting.”

Bucher’s work was clearly indicative of a literal place and time in her own life, but it also had a larger, cultural meaning. According to Stothart, she was investigating the physical boundaries between the human body and the domestic environments in which women, in particular, were often confined to.

The pieces shown in the exhibition center around the period when Bucher returned to a politically-charged Zurich after living in more progressive cities within the U.S. and Canada with her husband, who was a more traditional sculptor. After divorcing him, she began exploring more abstract forms of sculpture as well as feminist ideas like what it means to “take up space,” both in public and in private, as a Swiss woman.

(The Estate of Heidi Bucher/Courtesy Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul)

She primarily molded women’s clothing at first, which according to the exhibition description “both signified her interest in metamorphosis and served as a critical response to the rigid gender restrictions she experienced growing up.” By the time she started casting large-scale architectural structures, such as entire rooms, the concept turned into a personal and cultural commentary on removing oneself from the patriarchal past.

“She would literally pull the molds off the wall using her whole body,” said Stothart. “The material is strong and she wasn’t worried about the end result being perfect, or even conserving it. I’d say she didn’t want a piece to be an exact replica of space, but the memory of it, a ghost of it.”

Heidi Bucher: The Site of Memory opens at Lehmann Maupin at 501 West 24th Street, New York on April 29. A series of videos filmed by Bucher and her sons, Mayo and Indigo Bucher, will accompany the work, unveiling the poetic ways in which the artist spoke about her process and works.