The 2028 Summer Olympics (L.A. 2028), officially known as the Games of the XXXIV Olympiad, are coming to the Los Angeles region in just nine years. The event will make Los Angeles only the third city in the world, behind Paris and London, to ever host the games three times, and could potentially cement the city’s status as a 21st-century global economic, entertainment, and cultural powerhouse.

But what will it take to get there?

Though L.A. 2028 has been billed by organizers and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti as a no-frills affair that will make use of existing or already planned facilities—“we could do the Olympics probably two months from now,” Garcetti quipped in a recent interview—the effort has become a symbolic capstone for a variety of ongoing urban and regional metamorphoses across Southern California.

This symbolic quality has transformed the Olympics from a novel pipe dream into a rallying cry for what could be the most transformative urban vision the city and region have seen in over a generation.

When L.A. last held the games in 1984, city officials made history by holding the first and only Olympic games that turned a profit. The effort’s success resulted from a distributed event model that used existing university student housing and training facilities to create a networked arrangement of mini–Olympic Villages across a region spanning from Santa Barbara to Long Beach. Organizers also presented a novel media strategy for the games by fusing spectacular and telegenic installations by Jon Jerde and colorful magenta, aqua, and vermilion graphics by environmental designers Deborah Sussman and Paul Prejza with the marvel of television broadcasting, giving the impression of a cohesive urban vision for the games despite the fact that some locales were more than 100 miles apart from each other.

For 2028, local officials are hoping to repeat and surpass these successes. Garcetti, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and the private L.A. 2028 committee tasked with bringing the games to life have stated that unlike many recent Olympic games around the world, L.A. 2028 is designed on paper to break even, financially speaking—once again, mainly due to the lack of new purpose-built structures or venues that would be created for the event.

But these verbal and rhetorical gymnastics mask the full extent of the coming transformations and underplay both the scale of the games and the effects of what L.A. will have to accomplish to make them happen.

In reality, L.A. 2028 will not be possible without the completion of several key initiatives, namely, the ongoing expansion of Los Angeles County’s mass transportation network and the planned expansion and renovation of Los Angeles International Airport (LAX).

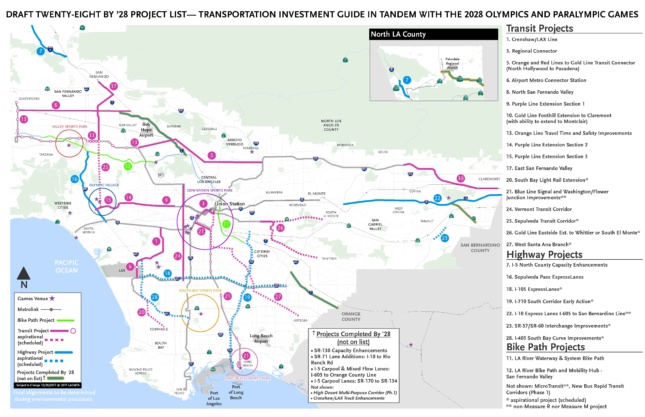

As part of a 50-year vision to double the size of the region’s mass transit network, Mayor Garcetti helped pass a sweeping ballot initiative in 2016 that will transform L.A.’s transportation system. Afterward, as Garcetti worked to secure the Olympic bid, he unveiled the Twenty-eight by ’28 initiative to speed up and prioritize certain transit improvements outlined in the 2016 plan so they can be completed in time for the games. In total, the plan aims to complete 28 infrastructure projects by the time the games begin.

One of the new transit lines due to be completed by 2028 will connect the southern end of the San Fernando Valley, where track and field and other events are to be held at the Valley Sports Park in the Sepulveda Basin Recreation Area, with the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where the Olympic Village is to be located. There, the university is busy preparing to add 5,400 new student housing units. Up to 6,900 new student beds are envisioned by UCLA’s latest Student Housing Plan, while up to 1,400 additional student beds could be brought online at several other UCLA-adjacent sites, as well. Though these projects are being built to help address a severe shortage of student housing, they will also ensure that when Olympians arrive to compete in 2028, their accommodations will be in tip-top shape.

The southern end of the UCLA campus will connect to the forthcoming Purple Line subway extension, another project that is being sped up in preparation for the games. The line will link UCLA to Downtown Los Angeles, where many of the transit network’s lines converge. The 9-mile extension to the line was originally planned in the 1980s, but was held up by decades of political gridlock. Between UCLA and downtown, areas like West Hollywood, Beverly Hills, and Hollywood are adding thousands of new hotel rooms in advance of 2028. Though the region is carved up into competing municipalities that have a history of working at cross purposes, it is clear that local decision makers are readying these districts to absorb a substantial portion of the incoming flood of international tourists. For example, a current bid to extend the forthcoming north-south Crenshaw Line— which will connect LAX with the Purple Line north through West Hollywood—has picked up steam in recent months in an effort to provide a direct ride from the airport to this burgeoning hotel and nightlife quarter.

L.A. 2028’s major sports park will be located at the L.A. Live complex in Downtown Los Angeles, near the eastern terminus of the Purple Line, where city officials have also been pushing for an expansion of hotel accommodations. Here, as many as 20 new high-rise complexes are on their way as the city works to add 8,000 new hotel rooms to the areas immediately surrounding the Los Angeles Convention Center, where basketball, boxing, fencing, taekwondo, and other sporting events will take place. This new district will be tied together by a nearly continuous podium-height band of LED display screens that could produce a modern-day equivalent of Jerde’s, and Sussman/Prejza’s visualizations.

Just southeast of Downtown Los Angeles, the Expo Line–connected University of Southern California campus will host the Olympic media village, which will also make use of existing dormitory accommodations, including a recently completed campus expansion by HED (Harley Ellis Devereaux). Gensler’s Banc of California stadium, also a recent addition, is located nearby in Exposition Park, the home of the 1932 and 1984 games, and will host soccer and other athletic events in 2028. In the park, a newly renovated Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will be retrofit with an elevated base to allow Olympic medalists to rise up out of the ground to receive their honorifics.

A trip south on the Crenshaw Line will bring visitors to the Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park, a new state-of-the-art stadium being built for the Los Angeles Rams National Football League team by Turner and AECOM Hunt that is set to open in 2020 and will host the L.A. 2028 opening ceremonies. The stadium will be much more than a sports venue, bringing together a 70,240-seat stadium and a 6,000-seat concert hall under one roof. Its total capacity for mega-events can be stretched to 100,000 people.

The stadium will also serve as an anchor to a much larger, 300-acre district that includes commercial, retail, and office buildings along with residential units. This development, formally called the L.A. Stadium and Entertainment District at Hollywood Park, is expected to be twice as big as Vatican City. Its staggering expense of more than $5 billion is tempered by the fact that it relies more on private financing than many other NFL stadiums built in the last three decades, which have traditionally leaned heavily on taxpayer funds and the pocketbooks of football fans. Besides the L.A. 2028 games, the stadium is also expected to host the 2022 Super Bowl and the 2023 College Football Playoff Championships.

Not far away, Los Angeles World Airports is working on a multiphase effort to bring two new terminals and dozens of new flight gates to the airport, including a $1.6 billion Gensler and Corgan–designed terminal capable of handling “super-jumbo” airplanes for long-haul international flights. The facilities are set to open by 2028 and will join new consolidated transportation hubs that will streamline private automobile, mass transit, and pedestrian traffic for the busy airport.

At the end of April, the L.A. 2028 organizing committee updated the estimated cost to be about $6.9 billion, up from the $5.3 billion figure submitted in the city’s bid. This still hasn’t changed the expectation that L.A. will at least break even on hosting the games.

These projects show that while the L.A. 2028 Olympics are being somewhat undersold by their boosters, the investments necessary to bring the games to L.A. are, in fact, quite vast. Ultimately, future Angelenos might look back quizzically at the muted rhetoric surrounding the games and the once-in-a-generation effect they will have on the region.