Archigram: The Book

Dennis Crompton, editor

Circa Press, 2018

$135.00

A dozen years ago, in the early stages of a dissertation, I found myself in the special collections room at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. To my left, a tweedy professor type softly sang Latin lines from an ancient leather-bound tome. To my right, a pair of art historians hunched intently over delicate sheets of 18th-century foolscap. As the attendant eyed me skeptically from across the room, I sat snickering at what appeared to be a sci-fi comic book.

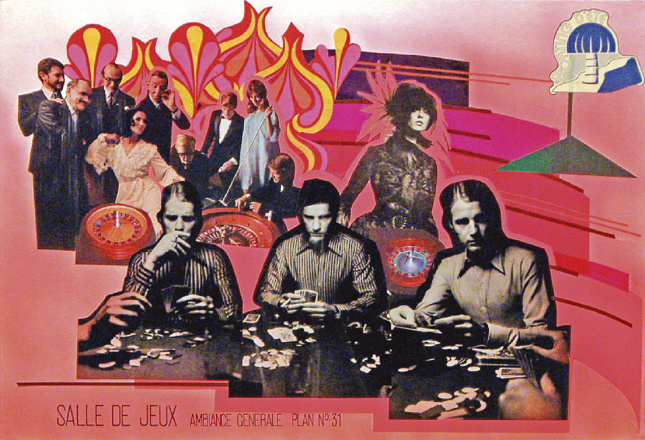

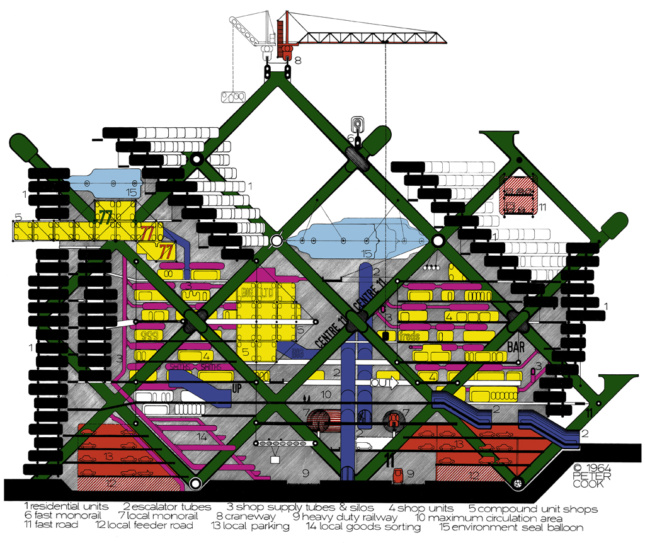

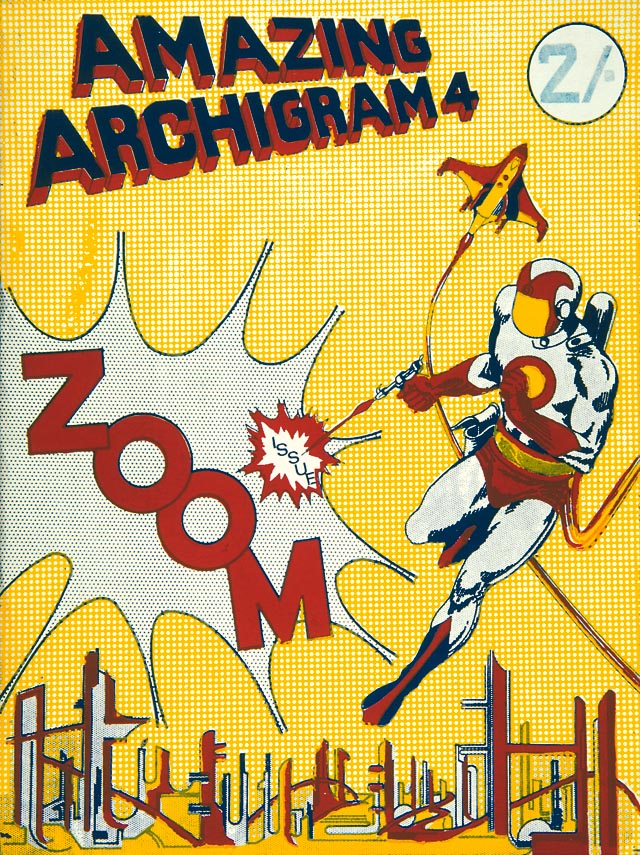

I had just unpacked all nine and a half issues of Archigram, and, frankly, I was a little giddy. There they were: The iconic first broadsheet of 1961, insisting that “a new generation of architecture must arise”; the iconoclastic third issue, advocating “a throwaway architecture” to replace society’s stubborn preference for permanence; the prophetic seventh issue, “Beyond Architecture,” which suggested that “there may be no buildings at all in Archigram 8.” (Spoiler: there were.) And, of cozurse, the breakthrough “Zoom Issue,” which in 1964 launched the group into the international spotlight, and which, in response to my giggles, was now shedding bits of desiccated cellophane tape onto the special collections room floor.

These infamous and now extremely rare magazines were produced—painstakingly, mostly by hand, run off after hours in the print rooms of unsuspecting London architecture firms—by a loose band of young English architects that eventually congealed into the famous sextet that took the name of the magazine as their own: Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron, and Michael “Spider” Webb.

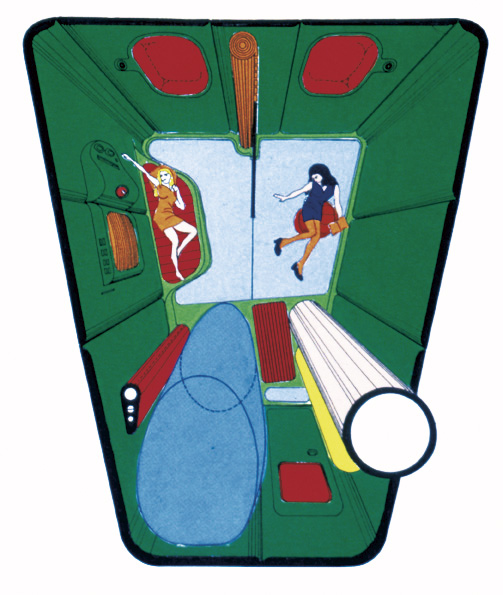

At first, the group used the magazine as an antidote to the dull, conventional work they chafed against in 1960s London. Early issues featured formally exuberant projects, mostly from their student days, as well as more recent competition entries by themselves and their friends. Loosely thematic issues related to expendability, science fiction, the city, and experimentation came next, followed by more polemic editions that aimed to drive architecture beyond building. A last “half issue” that featured work on the boards at the short-lived firm, Archigram Architects, appeared in 1974.

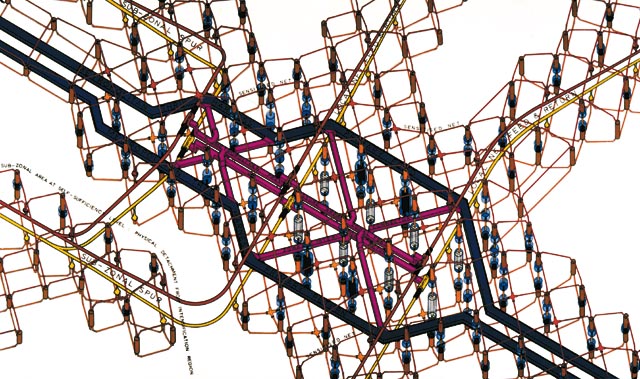

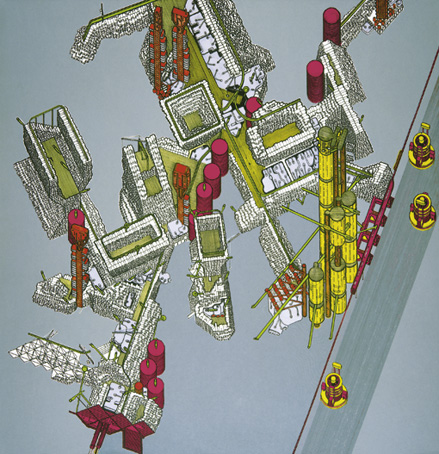

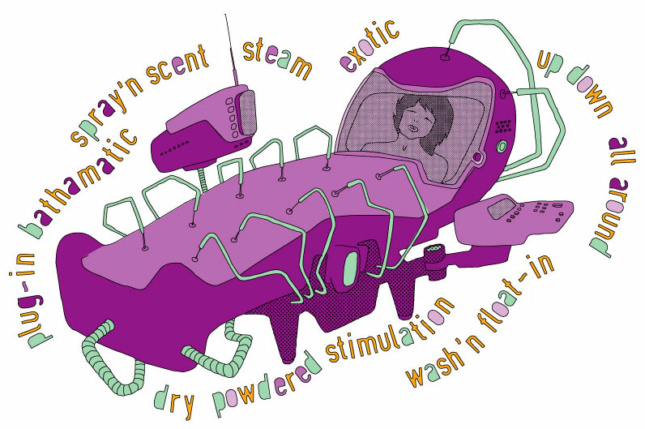

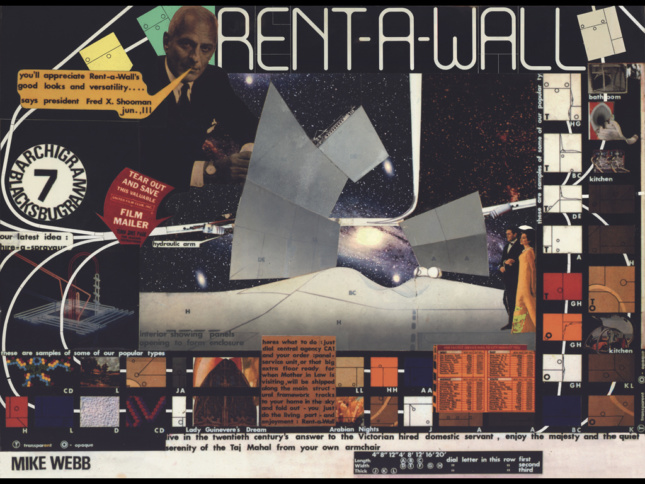

Archigram’s flagship projects—Cook’s Plug-In City, Herron’s Walking City, Webb’s Cushicle, and many more—all made important appearances in the magazine, as did the work of fellow travelers like Cedric Price, Buckminster Fuller, Nicholas Grimshaw, and Craig Hodgetts. By the mid-1960s, young architects from around the world were eagerly awaiting each new issue. By the end of the decade, a generation of architects had taken up the group’s technophilic agenda. Without Archigram, the early careers of architects as diverse as Rem Koolhaas, Thom Mayne, and Richard Rogers would be difficult to imagine, and the development of high tech architecture unthinkable. Ironically, by the time high tech had reached its apotheosis in the 1980s, Archigram had largely fallen out of favor, overshadowed by the heady critical culture of postmodernism and deconstruction.

While I was at the Getty, the group was enjoying something of a renaissance. A major exhibition had opened in Vienna in 1994. By 2005, it had toured sixteen additional cities and had spawned four catalogues. Simon Sadler released an informative monograph, Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture, in 2005. Hadas Steiner followed in 2009 with an excellent study, Beyond Archigram: The Structure of Circulation.

Yet even with all this, it was difficult to get a sense of the Archigrams themselves. Sure, some of the pages had been reproduced in print over the years, and all of them are now online at the Archigram Archival Project. Unfortunately, books and magazines tend to privilege Archigram’s projects over its publications, and the online archive, attempting to stave off piracy, provides images only at disappointingly low resolutions. The pamphlet’s idiosyncratic shape and feel—each with its own trim size, color scheme, graphic identity, and quirky design devices (a pop-up skyscraper centerfold in issue 4, a cutout megastructure model in issue 6, etc.)—remain elusive.

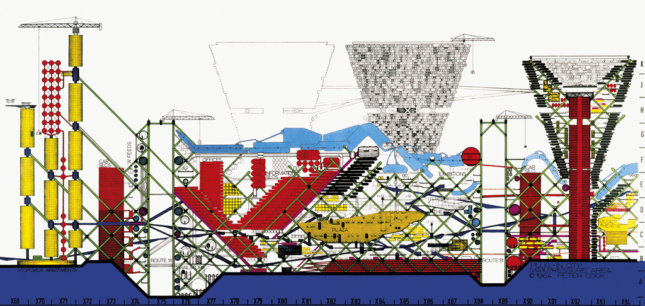

Archigram: The Book works hard to change this. Edited by Dennis Crompton and featuring extensive commentary from Peter Cook and other surviving Archigram members, this generous volume takes Archigram’s nine and a half issues as its central organizing device. Every issue is reproduced in its entirety at high resolution and in full color. The book’s large trim size (14 inches by 11 inches) accommodates reproductions at close to original size (sometimes enlarged), allowing careful study of the original layouts. It even includes the pop-up skyscraper!

Extensive presentations of key Archigram projects complement the magazine pages. Many of these feature gatefolds to afford the group’s expansive drawings the space they deserve. Even seasoned Archigram aficionados will find surprises here. The book presents canonical projects with a thoroughness that earlier publications generally lack, and lesser-known ones with equal intensity. Key moments in Archigram’s history—such as its 1963 Living City exhibition, a BBC television special from 1967, and the Archigram Opera, first performed at the Architectural Association in 1972—receive ample treatment, and seminal historic documents, such as Reyner Banham’s 1965 “A Clip-on Architecture,” are also included.

More documentary compendium than analytical treatment, this book (and Michael Sorkin, in his generous introduction) largely maintains the party line, best articulated by Banham in 1972, that “Archigram is short on theory and long on draughtsmanship,” and that it did what it did “for the sheer hell of doing it.” True enough. Archigram unapologetically privileged pleasure over politics and rarely bothered to unpack theoretical propositions beyond pithy captions. Its reluctance to address head-on the thornier sociopolitical implications of its work left its members exposed to searing criticism, particularly in the early 1970s. This book acknowledges but doesn’t trouble too much over those implications or Archigram’s relation to broader historical contexts of the 1960s and ’70s. (If these are your interest, head for Sadler’s and Steiner’s books, noted above.) The argument here— and, ultimately, I think it’s the correct one—is that Archigram’s graphic work, in all its exuberant, technicolor, detail-driven complexity, is what matters most.

So, does this sumptuous volume produce the same kick as fondling original Archigrams? No. The presentation is a little too slick to capture the raw excitement of the originals. But it’s still an awful lot of fun, and it comes closer than any previous attempt. Unless you’re ready to don the white gloves and head to the archive, Archigram: The Book is about as good as you’re going to get.

Todd Gannon is head of the architecture section of the Knowlton School at Ohio State University and the author of numerous works of architectural scholarship and history.