The United States of America of the 19th century was a civilization in rapid flux, subject to spiraling economic and demographic growth coupled with staggering socioeconomic inequality that manifested in deleterious urban poverty. Big Plans: Picturing Social Reform, on display at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston through September 15, 2019, effectively encapsulates the bold visions of the era’s patrician reformers with the living conditions of the urban poor that influenced their sweeping plans.

The exhibition is curated by Charles Waldheim, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture, Director of the Office for Urbanization, and the Ruettgers Curator of Landscape, and is largely made up of highly-detailed topographical and landscape maps, historical photographs, and personal mementos. According to Waldheim, “the show started with a very simple idea; could we take large urban plan drawings from the 19th century and treat them like works of art?”

For Big Plans, Waldheim hones in on four protagonists; Frederick Law Olmsted, the historic doyen of landscape architecture; Isabella Stewart Gardiner, the museum’s namesake and prominent member of the Boston Brahmins; Charles Eliot, Olmsted’s apprentice and prominent city planner in his own right; and Lewis Wickes Hine, the sociologist and prodigious photographer of the American urban condition.

Although contemporary controversies surrounding park construction largely center on budgetary or zoning constraints, the execution of such projects during the 19th century was remarkably radical in ideology and scope. Big Plans highlights the revolutionary nature of public landscape design with an initial focus on Olmsted & Vaux’s design for Central Park in New York, juxtaposed with an original hand-colored map by William Bridges for New York’s 1811 Commissioners’ plan that would place the gridiron street layout of Manhattan. In comparing these two disparate visions of Gotham at the onset of the exhibition, the curatorial direction quickly lays out the reformers’ visions of reshaping the rigid rationality of the industrial city into one that cultivated both economic and social progress.

The theme of correcting the societal ills of the industrial metropolis is continued in the second room of the exhibition with five-by-seven-inch silver gelatin prints produced by street photographer and sociologist Lewis Hines. Similar to contemporaneous New York-based social reformer Jacob Riis, Hines advocated for photography as an effective tool to prod for social reform. The images are not beautiful; as is the case with much early photography, many are overexposed and out of focus. However, aesthetics were not their purpose. The photos are a searing indictment of child labor, depicting young men and women toiling in industrial mills and sifting through fetid landfills in search of scrap materials.

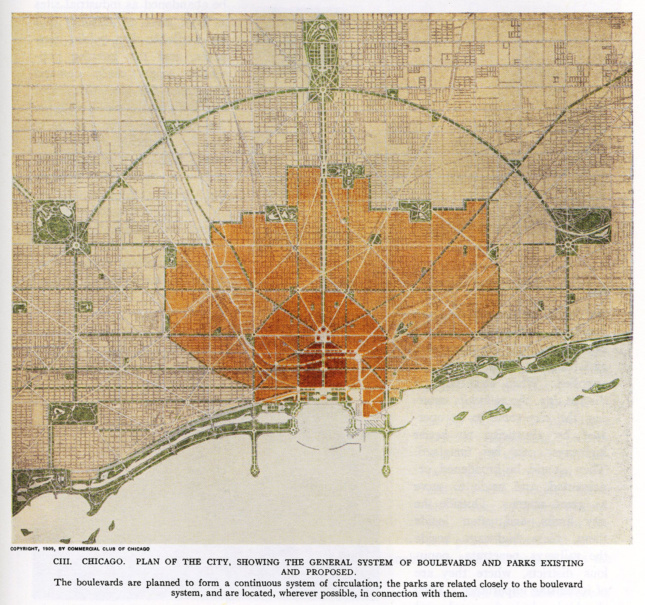

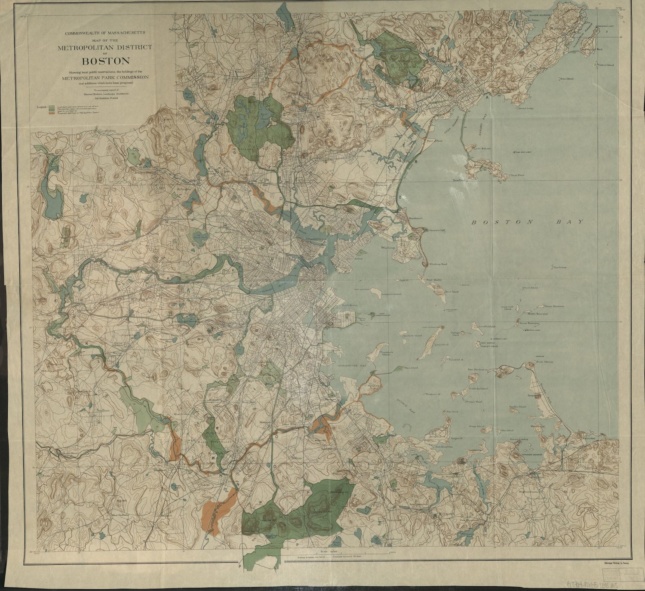

The remainder of the exhibition is largely a collection of drawings that plot out the expansion of the public realm and park space in Boston and Chicago, ranging from the Back Bay Fens to Jackson Park. Absent from the curatorial direction of Big Plans is a perspective from the urban working class and impoverished for whom the grandiose schemes were tentatively laid out for. This top-down perspective was a conscious decision by Waldheim to highlight the uneasy paternalism, or noblesse oblige, of the era’s social reformers. While not explicit, the exhibition begs the question of whether this condescension laid the groundwork for similarly grandiose urban renewal plans during the mid-20th century.

Big Plans: Picturing Social Reform

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

25 Evans Way

Boston

Through September 15, 2019