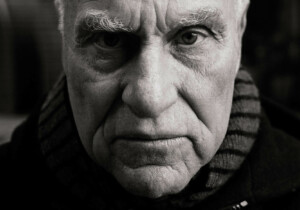

Dear Stanley,

It took you a decent nine years to write to Mies after he died, but I could only wait three days. You know, just to make sure. You did resign your tenure from the University of Illinois, Chicago twice, after all, so anything is possible. Less circumspect or hopeful, most of the other members of the tribe have already rushed in to saturate social media feeds with postings and posings, leaving no chance for any Miesian moment of silence in your absence. These days, three days feels like a lifetime.

As much as you talked all these years, there are still so many questions that remain: What was the connection between your lozenge paintings and Hejduk’s diamonds? What was the genealogy of your soft corner? What can I do to get fired?

One of your greatest attributes: You turned getting canned into an art form, always able to use crisis—indeed, design, and accelerate it—as a means to reinvent yourself and your work. When you hastily took leave of a coveted position at Harry Weese’s within a year, you quickly opened your own office. The first time you resigned your University of Illinois tenure, in 1970, led to one of the most productive and influential decades of your career. When you then returned to run the post-professional program, and next the entire school itself as director from 1985 to ‘93, you were able to transform an unlikely state extension school into the envy of the Ivys. Not surprisingly, this put you at odds with the senior faculty, who scurried to a newly appointed dean to have you dismissed as director. Not one to let others determine your fate, you immediately resigned your tenure a second time, and, with Eva Maddox, cofounded Archeworks.

During those UIC years, you were a Bulldog Buddha sitting on axis with the door, at a 60-inch round wooden Eames table in a ten-foot diameter mini-rotunda, less an office than an aedicula. We always assumed there was a revolver taped to the underside, near where the Herman Miller seal of authenticity would have been. Before one of your first meetings with a delinquent faculty member on whom you expected to go off, you asked your then-new assistant, Nancy Gislason, to nudge you under the table if you started to go too far. After her three discreet attempts of increasing urgency to follow your request, you turned and flatly reprimanded, “God damn it, Nancy, stop kicking me! I know I’m making an ass of myself!” You didn’t just know your limitations, you orchestrated their effective deployment.

There are so many memories of you in that circular Tiger’s den, which one never entered voluntarily, but was summoned into, if naive enough to walk carelessly within your distant cone of vision: “Garofalo, get in here!! Is K on drugs, or what?!” you once inquired of the New York theorist newly arrived as the Greenwald Chair. Never mind that Doug himself had just met Professor K; in your world we would all be our brother’s keeper. You would hold all of us, with your pointed emphasis, “per-son-al-ly responsible,” invariably for things over which we felt no control whatsoever. But that was your secret superpower: seeing and expecting more of us than we could perceive in ourselves.

Beyond your offices on Wells Street and in the A+A Building, you could hold court from any table in the city, from the Arts Club to Manny’s, Gene and Georgetti’s to Coco Pazzo—always, as you advised and practiced, with your back to the wall, and preferably in a corner. You could see them all coming: the anxious ones, approaching for a favor; the smiling ones, looking for the opportunity to stick it in the back; the accused, rushing to the door to avoid having to do their version of the perp walk before your studied glare. “He,”—dramatic pause—“is not generous,” you once declared in an exaggerated stage whisper of a former member of the Chicago Seven sitting two tables away. When said former ally came over to pay his respects, your first and last words, not surprisingly: “You,”—dramatic pause—“are not generous.” For you, there was never a difference between private speech and public act; what you said was what they got. In the architecture world that one could never escape once in your orbit, they were always there, populating the periphery of every restaurant, opening, and conference: the rice Krispies (“can’t hurt you, can’t help you”), the ones who were dead to you, the architects who drew like angels (and their opposite, those who “held their pencil like a civilian”), the writers “who owned the English language,” and those who you declared possessed “a discernible IQ,” (high praise) while tapping your temple with your index finger for emphasis.

You ordained quickly but could excommunicate with even greater alacrity. That is one reason our generation scrupulously avoided your various offices unless and until “invited.” We feared your wrath more than we coveted your approval. I suspect we also grew up believing the approval of one’s elders was more than a little distasteful, so we kept our thoughts to ourselves, wagering on the long game. This is not so true of the younger generation, your enthusiastic grandchildren, over-eager to please, to show and tell ev-er-y-thing, and with them you always seemed to indulge a patience we never took the time to notice. Did you mellow with age, or was it just the new mellownium?

When you wrote to Mies in 1978 (with ironic shock and genuine satisfaction), it was to inform him that his legacy was lost: modernism was moribund, IIT a sclerotic seminary, SOM an aging and unhealthy corporate carcass. Over the post-Miesian horizon, there was color, historical reference, pop, ornament, curvature, frivolity…talk. And today, four decades on, we are operating again on that same horizon you bequeathed to us, the one beyond The Titanic. When I returned to UIC in 2007 to reenact your role, you generously and without hesitation agreed to return as the inaugural lecturer, the first time you had set foot in Netsch’s labyrinth in the 14 years since your dismissal/resignation. Ever since then, UIC would paradoxically become much more a Stanley school than it ever was when you were in charge. After the diaspora and years in exile, “we” had won. The first Chicago Architecture Biennial borrowed its title from you (“The State of the Art of Architecture”), while the second elevated you as its de facto central protagonist (“Make New History”).

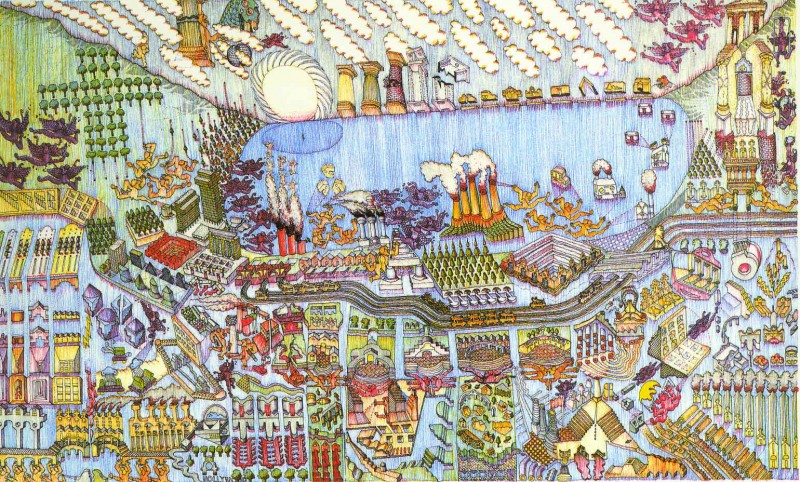

You had the temerity to suggest that Chicago was not just a city of pragmatics and profit, but of ideas and values, along with the talent to prove it and the tenacity to make others believe it. Through it all, you fought for discourse and argument and humor in a world dominated by marketing, platitudes, and unction. You remained committed to the belief that architecture, even in a place like Chicago, was a cultural event, that ideas and forms were connected—sometimes in your own work awkwardly or naively, at other times with shocking aura and simplicity. Just as you would take your work through serial attachments, quit, and move on, you would also direct the school through multiple and incompatible ideologies: pop-pomo, neo-classicism, deconstructivism, and the earliest moments of the digital, back when it was still manual. Others would mistake this as eclecticism, as a sign of your boredom, but in fact you were tirelessly demonstrating, training us in how to assume a position. It must have been exhausting to have to tutor a profession and a place so ill-suited to receive your lessons all those years, and no doubt it took its toll on your patience and your practice. Never willing to limit yourself to half a dichotomy, you would always rather fight and switch.

If future historians identify a third (or fourth) Chicago school, it will rightfully belong to you alone. Over the recent past decades, a multinational and multigenerational band of disparate architects have come to the city for Mies but left with Tigerman: from Ben Nicholson and Stan Allen to Pier Paolo Tamburelli, Jennifer Bonner, Kersten Geers, Momoyo Kaijima, and Job Floris. Of course, Sam Jacob and his partners at FAT were there very early, and his presence, along with other established visitors to the school, such as Paul Andersen, have helped establish UIC as a place to extend your initiatives. This is a significant and surprising genealogy of fellow architects and thinkers—colleagues, collaborators, combatants—and one not always identical with the locals you chose to coronate, whom to many of us seemed to embody the kind of self-promotion and branding you would increasingly condemn in other contexts. You often said that the practice of architecture was the perversion of the study of architecture, locating the core of the discipline with reflection and principle. But nonetheless, you seemed congenitally inclined—or was it just contextually compelled?—to elevate the striving practitioners who would surround you, in a replay of the fate of Mies’ disciples.

Frustrating as they were, those blind spots, those inconsistencies, were also part of your charm, a weakness for certain types. Despite your sometimes prickly exterior, you were an unrepentant optimist and romantic, a sucker for your latest discovery, always willing to assume that behind the smoke of others there was fire. Margaret McCurry, more measured and critical, saw that behind all that smoke there were often just mirrors. She was ultimately the tough and clear-sighted one over your 40-year partnership, the one you could depend on to keep you true to your highest ideals and best instincts, tolerantly rolling her eyes at your latest infatuations, all the while entreating you to eat your blueberries for their antioxidants. When you were blunt, it was often for effect; when Margaret was blunt, it was always for real. At once calculated and candid, the Tigerman-McCurry duo packed a powerful punch.

And then you left us, just 75 days shy of the fiftieth anniversary of Mies’s departure. Even for you, the symmetry of that possibility must have seemed too much. As we can already no longer think of him without you, the chronological correspondence would have been too trivial. What was it Rem once said, in an effort to rescue Mies from his acolytes, as you so often attempted? “I do not respect Mies, I love Mies. Because I do not revere Mies I am at odds with his admirers.” So let it be with Tigerman.

Love,

Somol