The Venice Variations: Tracing the Architectural Imagination

Sophia Psarra

UCL Press

List price: $45.00

Sophia Psarra’s The Venice Variations fulfills a dreamy mission of aggrandizing the titular city’s history and beauty while recognizing its fragility and potential demise because of climate change and overcrowding from tourists and their marine vehicles.

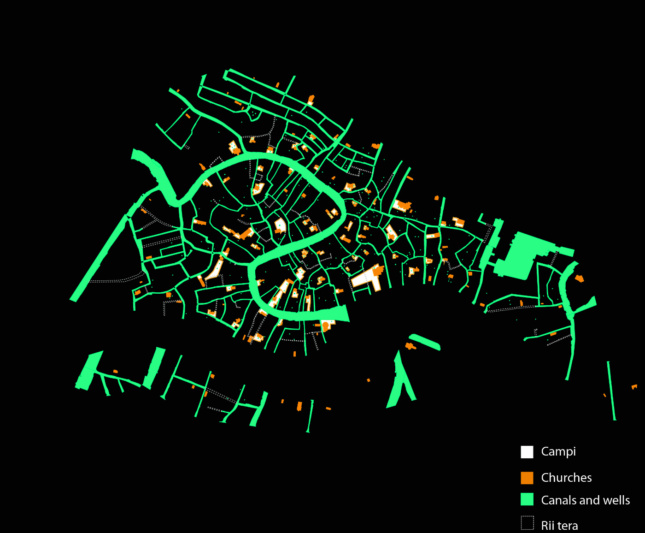

The beautifully designed book sets up the over-thousand-year-old city as paradigmatic but atypical. Social and physical analyses add to a discussion of its awesome historical architectural development and two contemporary works that the city inspired, Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities (1972) and Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital (1964). These projects exhibit an intensity of imagination commensurate with Venice’s idiosyncratic character. Psarra’s book points to the city’s republican governance, worldwide trading patterns, and physiognomy, especially its islands, as evidence of its fundamentally deindustrial nature, positioning its regeneration as an example worth following. Of course, Venice’s architectural importance has always been obvious: Books on Vitruvius were printed there, and Palladio’s thinking and buildings take central stage in its heritage of interwoven islands and structures. The irregularity of the city’s urban fabric introduces variability within an organic whole.

Psarra deals very carefully with the history of Piazza San Marco and its central position in civic and religious interpretations of the city. Its architects, Sansovino, Longhena, and Palladio, orchestrated their contributions to this special communal space to create specific views for the public to experience. The piazza accommodated many Venetian citizens and their commercial interests, as well as cultural rites—the author titles this chapter “Statecraft,” but the square welcomed stagecraft, too. Religious processions led by clergy and the Doge marked many occasions. Illustrations of the piazza and its surroundings by the author abound; these educational aids are present to a fault.

Italo Calvino makes his Invisible Cities mysteriously visible in print, a feat of vivid invention. This is a novel where plot is overtaken by expansive, thought-provoking fabrications. The merchant Marco Polo describes 55 cities as fantastical constructions to Kublai Khan, who rejoices in his empire. Our two protagonists, Khan and Polo, differ greatly: The former seeks order in his possessions, while Polo “seeks not-yet-seen adventures.” Invisible Cities attracted postmodern architects with its playfulness. The book juxtaposes images of lightness and coherence with images of entropy—disorder and ruin are the fascinations of our two protagonists. Although Polo refuses to discuss Venice, he provokes thoughts of it intermittently, and the city haunts the book. There is a play of numbers showing Calvino’s attachment to the Oulipo group of mathematicians, and he includes Polo’s descriptions and his and Khan’s dialogues and the number of combinatorial rules. Psarra shows some brilliance in this interpretation of mathematical patterns that few, including this author, fully comprehend. Though not an expert in mathematics, Psarra certainly seems to manage these complex concepts in the book. While architecture demands knowledge of mathematics, I wonder if there are architects who might appreciate the math of Invisible Cities as conveyed in The Venice Variations.

As the last project Psarra visits, Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital leaves a heavy imprint on the mind. Unlike the architect’s typically isolated buildings, Venice Hospital is meant to fit in with existing neighboring structures. Le Corbusier’s imagery is pertinent for understanding that of contemporary Venice. If Palladio’s San Giorgio Maggiore lies at the front of the city, the hospital would have marked its back door. The completed project would have been as radical as the first modern designs of the avant-garde—especially in its entrance from beneath, which recalls the Villa Savoye and the later National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo. Psarra also explores the hospital’s affinity with mat buildings as described by Alison Smithson. In fact, Venice Hospital’s place in the realm of architectural history lies in the province of Team Ten, with a neat precedent in Shadrach Woods’s Berlin Free University. The project engaged Le Corbusier’s attention for over nine years; after the master’s sudden death, Guillermo Jullian de la Fuente continued the work. Psarra tells the tale well: how the horizontal layout of the design sets up pivoting squares and nurse stations on the first floor and how the aggregation of cells flows horizontally to merge with the city. As in other signature buildings, Le Corbusier develops a system of squares and golden-section rectangles, which gives geometric logic to the spaces.