“Very soon it’s going to be a fact that in Copenhagen we ski on the roofs of our power plants,” Bjarke Ingels, founder of the Danish architecture practice Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), stated a couple of months prior to the completion of his firm’s Copenhill. Now, Copenhill, a new waste-to-energy power plant, has officially opened its doors after eight years (delays were primarily caused by safety approvals to occupy the roof). Beyond its hyped rooftop ski slope, the building also houses ski lifts, a ski rental shop, hiking trails, a cafe, and the tallest artificial climbing wall in the world.

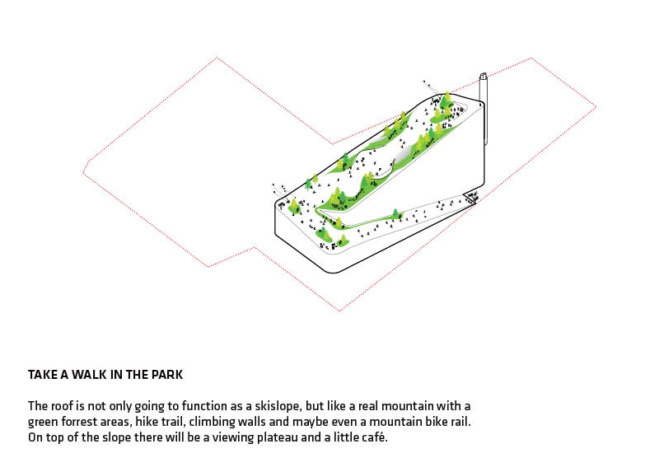

Copenhill, or Amager Bakke in Danish, ironically refers to the lack of hills in the southeastern Amager area of Copenhagen, a flatness that becomes apparent when one stands on the top of the 90-foot-tall “mega-brick” metal-clad building. “We do not have mountains, but we do have mountains of trash,” Ingels said. Turning away from the panoramic city views, one sees the 1,300-foot-long artificial ski slope designed in collaboration with Colorado’s International Alpine Design, the creators of many larger ski resorts around the world. The five shades of green of the ski slope surface membrane peek out from clean steam released from the nearby smaller chimneys. The gradient of green colors has been chosen to emphasize the sustainable agenda. The slope mimics—in a cartoon-like manner—a naturalistic terrain. However, the professional skiers testing it disappear within seconds, which makes the excitement of watching the skiers fade quickly.

A park, designed in collaboration with the Danish landscape practice SLA, runs along both sides of the ski track. The park was planned as a manicured Nordic wilderness with the ambition of attracting natural wildlife to the building. The metal facade, which will feature crawling plants, has setbacks for birds and other animals to inhabit. While the sustainable agenda informed details like the choice of plants, it can be questioned why the same consideration has not been given to the actual building materials. The choice of nonsustainable materials such as concrete, glass, steel, and aluminum is in many ways contradictory to the ideology of the building itself.

On the underside of Copenhill is Amager Resource Centre (ARC), billed as the world’s cleanest power plant. It provides 30,000 homes with electricity and 72,000 homes with heating across five municipalities, including Copenhagen. The heaviness of the technology that goes into a building like a power plant becomes very apparent when the glass elevator takes you from the ground floor up to the ski slope. An impressive interior landscape of monochrome silver-painted machines extends as far as the eye can see, and as Ingels explained, “the only design decision BIG was able to make on the inside of the power plant was to decide the color of the machinery—if it was of no extra cost.” The building in its entirety has so far cost 4 billion Danish kroner ($670 million USD) and is one of the most expensive construction projects in the recent history of Copenhagen. It is a high cost for a building that is supposed to be obsolete in the near future—plans are being drawn for a recycling system to take over all waste management.

The building—with the merging of interior industry and exterior recreative space—is what Ingels describes as hedonistic architecture. Copenhill should, in his eyes, be viewed as a landmark of an ambition to use clean tech to create a better environment, quality of life, and awareness of habits of consumption. The initial ambition was to have the 410-foot chimney discharge a smoke ring made from water vapor every time one ton of carbon dioxide was released into the atmosphere. There are no rings, but at least the exhaust is cleaned as much as possible before being unleashed above the city. As a contradictory landmark—the overall agenda is to have fun while increasing awareness of consumption—the building is officially part of the ambitious goal of making Copenhagen the world’s first carbon-neutral capital by 2025.

Christine Bjerke is a Copenhagen-based architect and writer and teaches at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation.