Architecture of Nature: Nature of Architecture

By Diana Agrest

Applied Research + Design Publishing

$49.95

“Representation, theater of life or mirror of the world.” Michel Foucault, The Order of Things

Presented as a 9-by-11-inch hardbound volume of full-color drawings, this sumptuously produced book includes interviews and writings alongside Diana Agrest’s design research as demonstrated by the work of her M.Arch II students at the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at the Cooper Union in New York City over a period of nine years.

Agrest is known for work that spans theoretical discourses in architecture, urbanism, semiotics, and gender. Her approach to semiotics has been neither purist nor essentialist; rather she takes a mediated view that argues that shifts in textual meaning are based on shifts in cultural context. In the 1970s and ’80s her view was also a kind of mediation between the Whites and the Grays, treating representation as a form of artifice, reflexively commenting on architecture’s inability to do more than this.

The Architecture of Nature exhibits (at first blush) a big pivot, with a new arena of investigation, if not perspectival view and methodology. The focus on nature, seen through geologic data (point clouds and weather data), is new to Agrest, yet the representations it produces are familiar as the aura and language of Cooper Union through multiple eras (under the leadership of Hejduk, Vidler, et al.).

If there’s a through line between Agrest’s early and late career, it rests here, in the primacy of (a particular type of) representation as the number one tool of architectural practice, with theory and building coming in a distant second and third. Less easy to appreciate is how this new territory relates to Agrest’s intellectual foundations in language, architecture, and urbanism.

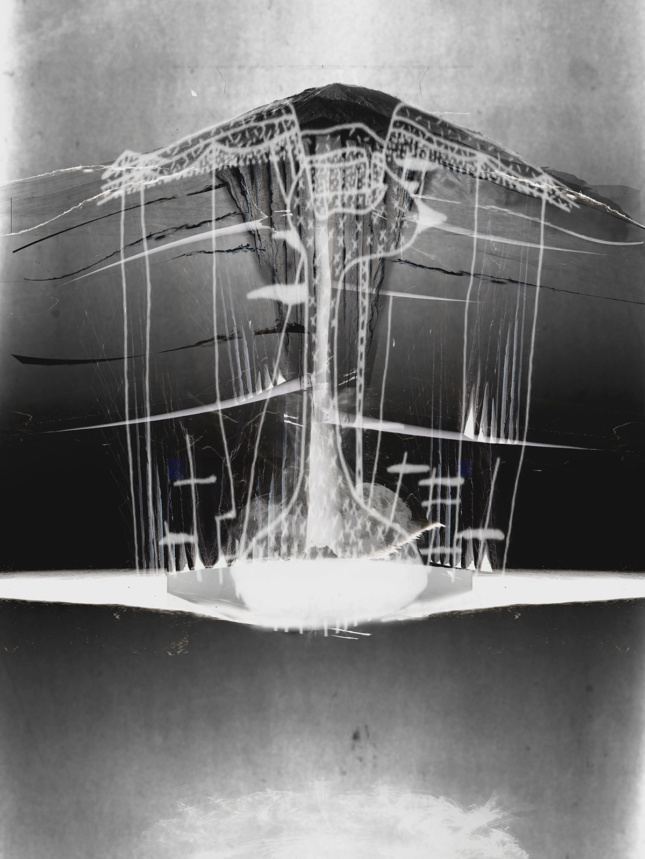

The drawings make geologic space seductive, in an ambient way. The works are more diagrammatic than spatial, more planetary and notational than human. They work through abstraction; delamination of layers; and schematic, atmospheric sections producing geometrically complex artifacts that are difficult to apprehend, yet in their finest moments, verge on the mystical. In their elusive effects, they seem cultivated like an endangered species to demonstrate the Cooper design imaginary and unique skill of the architect in re-presenting (in this case) science to the world.

In an interview with Agrest, which forms some of the finest content of the book, art historian Caroline Jones and science historian Peter Galison suggest that the work exemplifies “an embrace of the constructed nature of the image and how it comes into being.” Jones then offers the following critique: “It’s a sort of nature without us, except that the drawing is completely human in the way it is conceived.” The paradox Jones points out is this: Whatever “nature” is, we’re part of it, made of it, embedded in it. “Yet we can only ‘get to it’—that is, produce it as some kind of object for contemplation—by modeling, by presenting, by analogy, by metaphor, by externalization. We are of course a part of it all. But we have to pretend we aren’t, just to be able to think about it.”

Agrest’s stated ambition is not to be metaphorical but rather to visualize space-time. Jones suggests that avoiding metaphor is not possible (and possibly not desirable), suggesting Donna Haraway’s notion of “witness” as a more apt concept to engender complex ideas of entanglement. Agrest responds by invoking the transdiscursive and then “the process by which knowledge builds at the boundary.” In ecology we call this ecotone, but here it seems like getting caught in the dialectic of Jones’s caution.

In his interview with Agrest, science historian D. Graham Burnett suggests the work is “best understood as a kind of cataloging of contemporary gestures in the direction of a program—call it the ‘neo-sublime.’ This new program trades heavily on the aesthetics of information. In these cases, what we stand before that occasions a moment of negatory vertigo is not a big cliff or a deep cave but a colossal mass of data.” Burnett’s point is a salient one that this reader wishes had been further explored by Agrest. It’s part of a discussion that’s been percolating.

The material would also be enriched had Agrest made connections between the work she’s known for and this more recent design research less tacit—for example, the ongoing investment in notational design. Or to articulate ideas of gender and nature (if they are indeed still important) in her pivot to investigations of nature. She presents a too-simple discussion of “nature-gendered-female” in the introduction, and there’s no evidence of this thread in the design research.

Is it too far a reach to suggest that for Agrest, nature is the new object of the gaze, the so-called “scene of history” that in her previous work referred to the city? It’s one way to interpret an interest in the geologic past. Shifting focus from urbanism, Agrest has set her gaze away from the city and toward nature, and geology in particular. So it might follow that her previous articulations of a street—“Street: A scene in movement. The street is the scene of struggle, of consumption, the scene of scenes; it is infinitely continuous, unlimited in the motion of objects, of gazes, of gestures. It is the scene of history”—are now being transmuted to the immersive experience of geologic, or deep time. However, this is pure conjecture, so the reader is left to wonder if Agrest intends reinvention, recalibration, or promotion. The decision to include the 1991 essay The Return of the Repressed: Nature seems designed to place a golden spike in the calendar, a moment at which she began investigating nature. The essay, however, adds little to the more nuanced discourses with Jones, Galison, and Burnett in the book.

Given Agrest’s commitment to the transdiscursive, especially in the context of a body of work premised on an engagement with nature, it’s curious that the discipline of landscape architecture bears no mention, and in particular, the topological work coming out of the ETH in Zurich under Christophe Girot, as well as the work of Bradley Cantrell at Harvard and more recently the University of Virginia. Or the burgeoning interest in geology over the last 10 years or so in architecture, including Stan Allen’s Landform Building and the work of Design Earth, to name a few. This absence of peer context suggests that the real context for the book is not so much contemporary discussions about nature, but rather the legacy of representational virtuosity associated with Cooper Union’s School of Architecture.

Cathryn Dwyre-Perry is a landscape architect, adjunct associate professor at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture, and coprincipal of experimental design practice pneumastudio.