With Expo 2020 Dubai only one year away, we are at a crisis point to create a world-class pavilion to represent the best of the American people at the first World Expo in the Middle East. Architecturally brilliant US pavilions had been globally admired during America’s Cold War foreign policy efforts. As an architect and documentary filmmaker who filmed America’s abandonment of World’s Fairs through poor architectural design efforts in Face of a Nation, it is vitally important for me to share how a disintegration we’ve ignored for decades negatively impacts our American image abroad and endangers our hopeful vision of democracy.

The story of our U.S.A pavilion captures the commercialization of our national interests. The defunding and abolition of a strategic part of our foreign policy, the United States Information Agency (USIA), in 1999 marked the end of design excellence as a tenet of representing the American people at important public diplomacy events. Our research documents the failures of when privatization totally takes over our public interests.

Why is federal funding necessary for design excellence? Other countries demonstrate that they know the value of these events by paying for their own pavilions. Despite Reagan’s promise for “the energy and genius of the American people” at Expo ’92 in Seville, Spain, Congress blocked funds for the U.S.A Pavilion and we axed our American architect. The State Department scrambled to find “two exhibit buildings in moth-balls” for a makeshift pavilion the Spanish press maligned as “the American bra.” But architects know this message is most profoundly delivered through architecture. Congress eliminated the USIA (responsible for U.S.A. Pavilions overseas) in 1999 after we thought we had won the Cold War—ending public-sector support and beginning the battle of ‘who should pay.’

Debacles at the 2010 Shanghai World Expo and 2015 Milan World Expo are evidence enough that pure private-sector funding is a recipe for trouble. Shanghai’s U.S. Pavilion locked visitors inside and wasn’t even designed by an American architect! The richest country in the world didn’t raise enough to pay for Milan’s U.S. Pavilion, so the American companies who created it suffered significant financial losses. Diminishing World’s Fairs as “just trade fairs” and lauding public-private sector partnerships, the federal government has forced the private money to pay for our international exhibitions for the last 25 years. But public-private partnerships only work when the public sector pays as well.

Other countries believe World’s Fairs are more than “just trade fairs,” with an important public diplomacy role, by engaging people around the world. More than 60 years after the USIA’s founding principles were defined “to understand, inform and influence foreign publics” about American ideas and values, our practice appears to be antagonizing the world instead. Rather than “winning hearts and minds” with face-to-face communication in “the last 3 feet,” our generation is tweeting, chatting, or cyber-bullying each other over thousands of miles.

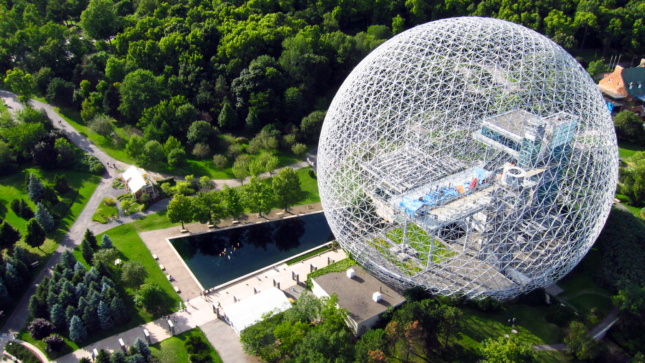

Most people don’t know the potency of our senses in the brick and mortar world. Architects use design excellence to kindle the viewer’s emotions; a powerful persuasion without words. Innovative design captures futuristic visions of hope, effecting optimism and industry for generations to come. Awe-inspiring examples of the power of World’s Fair architecture influencing people for hundreds of years include the Crystal Palace and the Eiffel Tower. Our film follows the late Jack Masey, a U.S. foreign service officer/behind-the-scenes genius whose vision shaped the most innovative U.S.A. Pavilions from USIA’s early years. These pavilions inspired nations with a better idea about who we are as a people; including the setting for the 1959 Kitchen Debate, Buckminster Fuller’s Expo ’67 geodesic dome (inspiring Disney’s Epcot), and Davis Brody’s Expo ’70 air-inflatable—the largest in the world, where the Apollo 11 moon rock was shown.

By the late 20th Century, U.S. trade interests had unconsciously projected a corporate, consumer image of American values and culture. The 21st Century saw the development of the internet, social media, and new digital platforms for people to communicate in cyberspace. These realms convinced many that international gatherings like World’s Fairs were costly, wasteful, and obsolete. No one anticipated they might become “virtual spaces” to spread false narratives about America. Going to the World’s Fair with design excellence is not only a chance to defend our American image in “real space,” but an opportunity to engage the world in the wonder we inspired when we did things right. American design excellence must be used to deflect the attempts to diminish our democracy.

We must tell our story better to the world. It took a bipartisan Congress to underestimate the importance of design. It will take bipartisan Congressional support to fund and fix it. Special appropriations through Congress were essential to do things right during the Cold War, and federal funds are critical again to safeguard our vision of democracy. Because architecture reflects who we are. If we ignore what we see, we lose sight of our own vision. What keeps our dream alive? Going to the World’s Fair with our best American design talent might make all the difference.

Mina Chow, AIA, is a documentary filmmaker, founder and principal of mc² SPACES, and an adjunct associate professor at the USC School of Architecture.