This year’s Monterey Design Conference (MDC), held from October 25 through 27 was hot and crowded. With over 900 registrants, the main hall was packed, and the overflow lounged in comfortable chairs in the chapel. There was music around the campfire, and for the first time in my memory, marijuana smoked openly. The bar was in full swing. It was the “partiest” MDC in ages.

As David Hecht, the new chair of the MDC committee told me, they hoped that each participant could find their own theme—this time, it felt like “Humility Not Spectacle.” Many architects mentioned inspirations, teachers, and mentors.

On Friday, October 25, the first headliner was Alberto Kalach of TAX/Taller de Arquitectura X in Mexico City. He set the tone with humor, humility, self-effacement, and beauty. As Kalach said, “We are the canvas of the planet” and advocated reconnecting vegetation and water systems to create integrated cities.

Kalach moved on to show some of his best-known projects, including his own office building and his controversial “hanging” library in Mexico City (a concept recently mimicked by the renovation of Cornell’s Mui Ho Fine Arts Library). Like much of Kalach’s work, it felt as if the structure has grown out of the garden. Every project Kalach shared integrated nature in a way most Californians advocate, but don’t often achieve in practice.

Mark Cavagnero, one of the luminaries of the Bay Area scene, linked his personal story to his architectural one. Edward Larrabee Barnes was Cavagnero’s mentor and early employer, and Barnes was one of Marcel Breuer’s students. Cavagnero knew some of Breuer’s Connecticut homes as a child, as well as the Torin Building, where Cavagnero’s father worked. These early lessons in what Cavagnero calls “the long, low line” still hold.

Cavagnero’s presentation was humble and precise, similar to his buildings. One of my favorite Cavagnero projects is the subtle renovation of the Oakland Museum of California, originally designed by 20th-century modernist Kevin Roche. Cavagnero inserted alterations that could be easily identified yet support the original concept.

While most of Cavagnero’s horizontal buildings have very developed ideas about space, light, and a limited palette, he is just beginning to apply his reductive and horizontal approach to larger scales. The San Francisco Public Safety Campus he designed with HOK looks a little tough. More recently, with SOM, he has helped turn the bland Moscone Convention Center into something more distinctive.

Following this lecture was the surprise announcement of the 2019 Maybeck Medal, bestowed to another San Francisco modernist, Jim Jennings, who received a well-deserved standing ovation.

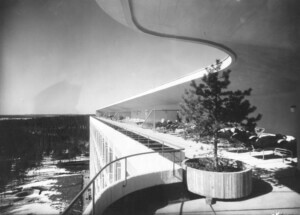

Saturday’s first speaker, Yvonne Farrell of Grafton Architects in Dublin, Ireland, stole the show. Along with her partner Shelley McNamara, Farrell has picked up the modernist mantle and moved it forward with gentle good humor. Although their powerful buildings are not exactly humble, they read as humane. Farrell cited Jørn Utzon as one of her influences, beginning with his porch in Mallorca.

One of Farrell’s main themes was architecture as the new geography, the container of our lives. Like Cavagnero, she does not use context as a pattern for replication but as inspiration for new forms, shaped with light and space.

Saturday’s second headliner, Brian MacKay-Lyons, is another architect of place. One of his memorable phrases was “buildings hung from the horizon.” Although his approach is very different from Cavagnero’s, he faces a similar challenge. How does one scale up? MacKay-Lyons sticks to some of his basic ideas of framing views and seeing light and air as free. But his larger buildings, although derived from place, don’t feel tucked in the way his smaller buildings do. He also cited Charles Moore as an influence.

Moore seemed to hang over much of the conference like a guardian angel. Bob Harris of Lake|Flato knew Moore in Austin and mentioned the sparkle in his eye. More than the other presenters, Harris focused on his practice, how it was organized, and emphasized the value of collaboration. One of the core values of Lake|Flato’s practice is restraint, and this came across at a variety of scales.

Charles Moore’s former business partner in San Francisco, Donlyn Lyndon, talked about their early years together at a session with architect and historian Pierluigi Serraino. Moore wanted architecture to create new kinds of spaces that enhanced the sense of place. It was a kind of humble position that he staked out. But as Lyndon said in his presentation, “he held onto the pencil,” which meant control.

In addition to showing Moore’s hedonistic exuberance within his own small Orinda house, Lyndon presented images of the Hubbard House (1959) in Corral de Tierra. Lyndon also said something critically important about Moore: “He was thinking about the movement of the body,” a key thread in the work.

Over drinks afterward, longtime MDC committee member David Meckel of California College of the Arts joked, “It was well into day two before we saw any parametric design!” That sums up the 2019 Monterey Design Conference pretty well.