In early February, when Architectural Record broke the news that President Trump might force classicism on future federal architecture, the design industry erupted in anger. Despite the fact that the rule still hasn’t been enacted weeks later, the frustration remains for many.

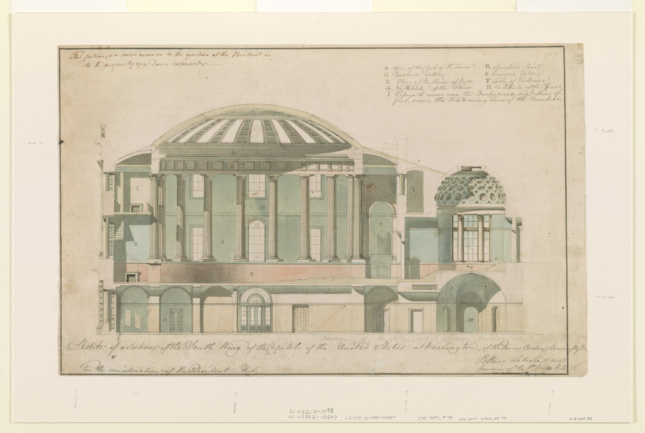

Jean Baker, professor and author of Building America: The Life of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, argued that Latrobe, who contributed to the design of some of America’s most important government buildings, including the White House and the United States Capitol, would be “aghast at any politicizing of his designs.” The process of designing federal structures in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when the Capitol was built, was fairly informal, she said. President George Washington solicited designs for the Capitol through a competition advertised in various newspapers, and the resulting building was unfinished when the government moved there in 1800. Latrobe pushed for the Capitol to be a significant and permanent structure and worked on the north and south wings until the War of 1812 diverted funding.

“Latrobe was very conscious of the connection of architecture to the political ideals of the United States,” Baker told AN. “He argued, in a famous oration that was three hours long, that architecture, along with other arts, served freedom, and in Greece and Rome had strengthened those governments and would do the same in the United States.”

According to Baker, Latrobe’s vision for the Capitol was for it to be functional, rational, and understandable “without any need for expert explanation, as he believed some European buildings needed, or a connoisseur for appreciation.” Opponents of Trump’s draft order have argued that a return to neoclassical architecture would result in buildings inspired by another time that need some amount of translation for the present or elevate certain cultural traditions over others. The National Organization of Minority Architects, for one, wrote in a statement that such structures embody “cultural exclusivity” and “would signal the perceived superiority of a Eurocentric aesthetic.”

The contemporary buildings cited in the draft order “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again” have “little aesthetic appeal” according to Trump, but have been lauded elsewhere. Both Arquitectonica’s Wilkie D. Ferguson, Jr. U.S. Courthouse in Miami and the Morphosis-designed San Francisco Federal Building have won national design awards.

Two weeks after the story broke, former presidents of the AIA added to the organization’s earlier, immediate reaction in a letter of dissension to the White House asking Trump to reconsider the proposed mandate. They argued that dictating a uniform style of architecture, whether neoclassical or modern, sets a precedent for suboptimal design.

“The investment of federal funds into public buildings demands an appropriate return on investment to the American people—the taxpayers,” the former AIA presidents wrote. “That return is not guaranteed by stipulating a singular design style; it is achieved by engaging in a rigorous process that engages the most qualified and experienced design and construction professionals. In fact, it is well-known that neoclassical design often equates to higher construction costs and extended time schedules for project completion.”

The issue extends beyond neoclassical aesthetics—material choices would be affected, as well, which would influence building performance and carbon footprints. If a certain style dictates the use of copious amounts of stone, then contractors have to seek out manufacturers and quarries that can deliver the quantities needed for a federal project with such a large square footage. Baker said that Latrobe, even in his time, sought out local materials for his buildings. The breccia marble found in the Capitol’s National Statuary Hall, for example, was quarried along the Potomac River. “Pure neoclassicists would demand marble,” she noted, which could complicate sustainable supply chains and material sourcing decisions.

Federal projects located within the U.S. wouldn’t be the only built works affected by the order—it could affect the renovation and construction of embassies around the world. Many recently announced projects, like WEISS/MANFREDI’s update to the Edward Durell Stone–designed U.S. embassy in New Delhi, would have to reflect classical European values of architecture instead of a reinvented modernist aesthetic fit for India’s climate. Sources who spoke anonymously to AN said that design-excellence advocates have been fighting for high-design federal architecture at home and abroad for years in Washington, and it’s been an ongoing battle.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the U.S. General Services Administration oversees the construction of overseas embassies, which is in fact managed by the State Department.