Although he never reached the fame of neoclassical contemporaries such as Claude Nicolas Ledoux and Étienne-Louis Boullée, French architect and artist Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757-1826) remains a draughtsman of immense vision, from a turbulent era that witnessed the collapse of the Ancien Régime and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. Luckily, in the months leading up to his death, the artist bequeathed his vast collection of 800 drawings to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which launched the first retrospective Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect at the beginning of 2019. The show’s latest iteration at The Morgan Libary & Museum is the first in New York City and is a succinct and, truth be told, sublime survey. The exhibition includes sixty of Leqeue’s drawings and is curated by the Morgan’s Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints, Jennifer Tonkovich.

Lequeu was born in 1759 to a long line of master carpenters in Rouen, the provincial capital of Normandy. His early career began with accomplished studies at the Rouen School of Drawing followed by a string of urban planning and architectural commissions, and a migration to the imperial capital of Paris in the waning days of the Bourbon dynasty. Initial professional success and a multiyear pilgrimage to the customary landmarks in Italy ultimately fizzled, and Lequeu settled into the relative monotony of governmental bureaucracy. Perhaps as a creative outlet to deflect from hampered ambitions—not dissimilar from the architectural fantasist A.G. Rizzoli—Lequeu produced hundreds of pen and wash drawings ranging from self-portraits to invented landscapes populated by renderings of imagined buildings and monuments, many found in his quasi-handbook Civil Architecture.

“One of the big takeaways, for me, has been despite the official recognition, and in the absence of any sort of validation, he continued to draw, to envision new worlds, and incorporate novel elements,” said Jennifer Tonkovich. “He never gave up his idiosyncratic vision.”

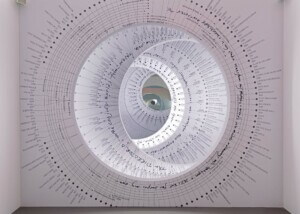

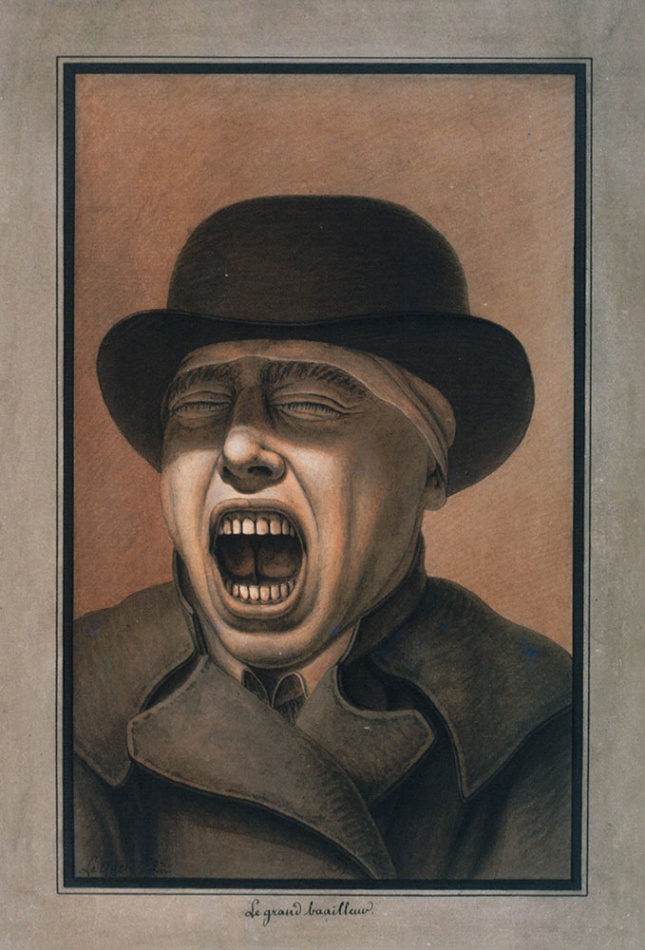

The Morgan, with its flamboyant marble flooring and intricate classical detailing, is a fitting curatorial space for the show. The exhibition room is split between an outer and inner ring: The former introduces the subject with a series of self-portraits—mouth agape and jowls creviced—and largely follows the trajectory of his drawings of architectural manuals to spectacular renderings produced at night within the confines of a claustrophobic Parisian apartment. The quality of penmanship is impressive unto itself, but drawings such as Design for a Living Room at the hôtel de Montholon and the Apotheosis of Trajan highlight the profound depth of ancient architectural knowledge at Lequeu’s fingertips, with an acute syncretism of Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indo-Chinese influences.

While the architectural drawings are demonstrations of vivid imagination, all remain rooted in the clear and calculated logic of profile, section, and plan. Not only are Corinthian orders and cenotaphs deconstructed into their composite parts—base, shaft, capital, and entablature—but the tectonics behind their engineering are legibly, and fantastically, expressed.

Although the human body and erotic themes extend across Lequeu’s oeuvre, the center of the exhibition focuses on his works of more explicit playful sexual depictions. With the same level of detail applied to his architectural renderings, thighs and crotches are splayed and labeled, nuns lift their habits to reveal corseted breasts, and buttocks stand athwart.

The timing of the exhibition is prescient in the current political moment—classicism is cast as a revanchist tool by reactionaries to reestablish Eurocentric cultural norms and artistic conformity. The retrospective’s response is an art historical broadside against that perception: “Lequeu is trying out ideas, exploring non-western forms, testing the limits of structures, experimenting with unorthodox decoration,” continued Tonkovich. “He is not bound by rules or convention, and the result is designs that are clever, mysterious, beautiful, and mystifying.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect

The Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue

Through May 10, 2020