The following interview was conducted as part of “Building Practice,” a professional elective course at Syracuse University School of Architecture taught by Molly Hunker and Kyle Miller, and now an AN interview series. On November 7, 2019, Sachio Badham and Tommy Wang, students at Syracuse University, interviewed Anna Puigjaner, principal of the Barcelona-based architecture office MAIO.

The following interview was edited by Kyle Miller and AN for clarity.

Sachio Badham and Tommy Wang: We know that MAIO has four partners. How and when did the four of you come together to begin the practice?

Anna Puigjaner: We started practicing together in 2012, following the social crisis in Spain in 2011. At that moment, there was an economical niche that we could fit into, and we also felt the need to involve ourselves in that as designers. The four of us shared interests and ambitions, and wanted to create a space for discussion and designing together. The crisis encouraged us to open this space, not only for us to practice together, but also to collaborate with other colleagues and friends in fields related to architecture—graphic design, landscape architecture, and engineering, to name a few. We thought that situation was going to be temporary, but it ended up being quite productive and defined a lot of what we do today. We’re a family in that space… we all learn a lot from each other.

How do your previous academic, personal, and professional experiences influence your approach to practice today?

I believe that every generation responds to the previous one. Through our work, we are responding to the previous generation of architects in Spain. Where we studied in Barcelona, there were many limitations. For instance, color was forbidden! So, for us, it was necessary to break through some of the limitations that were imposed on us when we were students. Also, the relation between theory and practice was lost after the Olympic Games in Barcelona in 1992, because of all the practices were so busy with commissioned work… suddenly, the theoretical side was lost. Since the beginning, we aimed to combine writing, theory, and practice, partially as a response to that time that came before us, which was mostly service-based practice and not much criticality and speculation.

Do issues outside of the traditional boundaries of the discipline of architecture influence your work?

When the economic crisis hit Spain in 2008, most of the architects we knew left to work abroad. We stayed, and we started gathering with artists and designers because they were the only ones left in the city. We were deeply influenced by the underground practices that were able to survive during those years. For instance, we began designing many things other than buildings—art objects, temporary installations, pavilions, etc. It was an exercise that was super necessary for us to push the discipline beyond its boundaries. This moment also influenced my approach to teaching. I was encouraging my students to read philosophy, rather than architecture. I wanted them to engage with contemporary issues rather than historical. In a moment of social change, if you don’t understand how and why you are living, you cannot meaningfully respond through design.

What about personal interests of yours… how do they influence the work?

Well, from the beginning of my time in school, I was interested in housing, partly because I was really uncomfortable with how housing—collective housing and, not only public, but also private housing—was approached in Spain. I built up a critical awareness of the production of too many low-quality housing projects in Spain. I started to look at cooperative housing from the 1970s that was really popular in Spain and was very successful. At that time, cooperative housing was developed by banks to promote collective living and positive social reform. Meanwhile, in the 2000s, banks lost interest in promoting well-being and engaged social and political action through housing. Housing became a mere financial issue. The notion that housing could be tied to social issues was totally lost. So, that’s why I started to look at—and continue to look at—housing from a critical perspective.

Your office is the only one we’re connecting with that is not based in North America. How does being based in Barcelona influence the development and execution of your projects?

Now that I spend a lot of time in the U.S., I understand that problems in the U.S. are really different from problems in Spain and throughout Europe. So, we are still a local practice, but we have to be aware of the global market in order to know how to navigate and grow. Compared to the U.S., in Europe there are mostly small practices, which provide quite a richness in the landscape of architectural practices. The economical weight of running a small practice in the US seems quite a lot to overcome. So, in the U.S. there are far more larger firms, and developers have far more power. Despite the challenges, I’m always encouraging students and young architects in the US to find cracks in the system, to be proactive in finding ways to practice that don’t rely on partnering with corporate offices or waiting for developers to call and ask for your services.

Do you intentionally pursue a particular aesthetic sensibility across projects, or do the aesthetics of your projects emerge naturally relative to the project’s context and parameters?

That’s a tough question! The aesthetics of our projects evolve as we evolve as an office. The four of us are quite diverse. We have different interests and different backgrounds. So, our aesthetic predilections are different as well. That’s positive. The outcomes that we achieve in our projects are the result of long conversations and debates between the four of us. For us, it’s important to take time to evaluate the status and evolution of cultural constructions and aesthetics, which are always changing. If we do not also evolve, our identity will become fixed and we will be left behind.

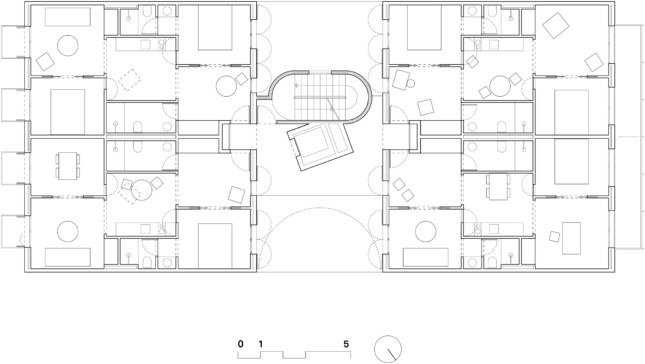

We’d like to ask questions about 110 Rooms. We know that the plan organization is inspired by Eixample’s original apartment typology. Do you typically utilize historical precedent in your projects? Also, what is the role of the context in 110 Rooms?

This question is a bit related to the previous one, because architecture is stuck in-between competing demands. Architecture has to be timeless because buildings last for decades or even centuries. At the same time, architecture has to be rooted in a contemporary context. Because of this, we always look at the context of our projects and the history of the context as a starting point. Regarding the plan organization… we acknowledged the mirror conditions that we have today with the 1970s. Concepts of flexibility were on the table and really important at the time. But the way we understand flexibility today is very different from then. So, our daily life changes slowly.

Our needs might change from one year to another, or every five years, but they don’t change from one day to another. We pursued flexibility not by means of moving walls, but rather, in the relationship between fixed space and assigned activity. In 110 Rooms, we are making a claim that housing should be much more generic and should lack preset hierarchy. Nowadays, most of our market is defined for the prototypical family of two parents and one or two children. Meanwhile, our society is much more diverse. So, the concept of flexibility that we’re dealing with is related as much to use and activity as it is to space.

What types of projects would you like to work on in the future?

It’s always good to have a five-year plan! Once a year, the four of us meet to discuss the next five years. We know that every decision that we make will influence the future. So, if you decide to do one project or another, it’s likely going to influence what comes next. One thing we always agree on is to maintain a balance of big projects and small projects, super practical projects and super conceptual projects. This is our ideal situation because the most conceptual and small projects usually influence the large ones. I’m saying this because they have different temporalities. So, an installation might take three or four months, but a building takes a minimum of three year to complete. So, the smaller, short term projects provide us with opportunities to experiment with ideas that might influence the large, long term projects.

What has been the most rewarding moment of your professional career?

The most rewarding moments are when you witness the positive impact architecture can have on an individual. From their perspective, it’s not something that comes immediately, so you have to be patient. But when you meet a former client, and they share how much their life has changed as a result of living in a space you designed, it’s very rewarding. It seems obvious, but good architecture is really important in order to make everyone happier. If you have a good space to live and work in, you are more likely going to be happier. Most of our society is not aware of that. We’ve been fortunate to have opportunities to create spaces for people to live in. And some have shared with us how they’ve been deeply transformed by space we designed. That’s such an extremely nice compliment to receive.