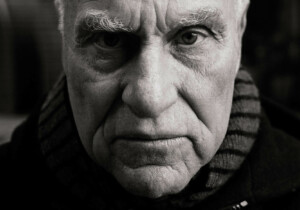

Michael Sorkin, inimitable scribe of the built environment and leading design mind, passed away in New York at age 71 last Thursday after contracting COVID-19. Survived by his wife Joan Copjec, Sorkin leaves behind an invaluable body of work, as the following tributes—from friends, colleagues, peers—readily acknowledge. This is the second of a two-part series; the first can be read here.

Jie Gu, director, lead urban designer, Michael Sorkin Studio

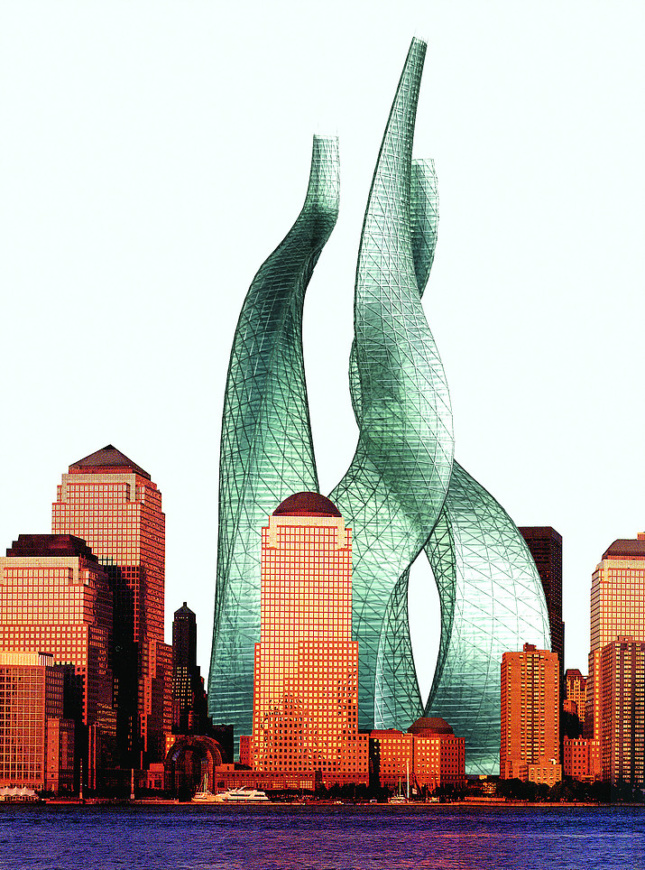

“Jie, can you wiggle these buildings and make them sexy?”

“Jie, can you let me have some fun?”

“Jie, I had a dream last night. I think we need to try something new.”

“Jie, I will be in on Saturday, leave me something not boring.”

Michael, I miss the dynamic “creatures” you directed me to model.

Michael, I miss the tremendous beauty of your red-colored sketches.

Michael, I miss your utopian dreams for sustainable cities.

Michael, I wish I could have spent more time with you.

“Jie, if I go, you must use our legacy to keep going in the direction that seems best.”

These were his last words to me, and they will resonate with me forever.

Makoto Okazaki, former partner, Michael Sorkin Studio

Like Matsuo Bashō, the most famous haiku poet of Edo-period Japan, Michael was inspired by his many journeys. The last email I received from him—on February 5th, 2020—was about a hospital in Wuhan built in just ten days to treat those infected with COVID-19. It was located within the area where we had, in 2010, designed a masterplan, what we called Houguan Lake Ecological City.

In the same email, Michael expressed his disappointment over having to cancel a trip to China due to the spread of coronavirus. He was often on business trips, which took him all over the world. On one occasion, he joked to me that a secret of his happy marriage was traveling alone a lot. I took this as advice!

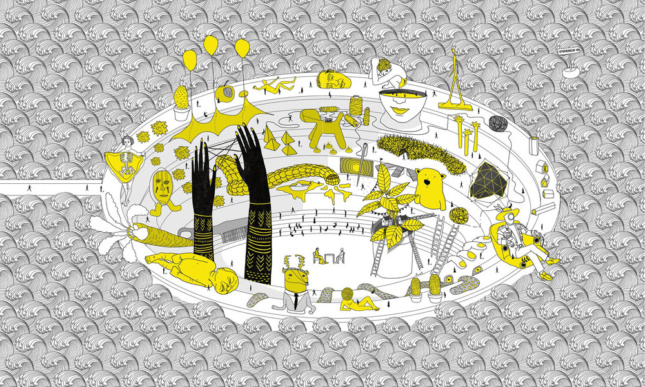

Wherever he was, Michael would send his inspirations and sketches back to the studio in New York City. We would develop them into a design proposal—not without some miscommunication—then toss it over to him. Back and forth, until we landed on something both strange and fantastic. We were thrilled by the whole process.

Michael, you’ve now left on another journey. We all miss you.

Deen Sharp and Vyjayanthi Rao, co-directors, Terreform Center for Advanced Urban Research

Michael fizzed with ideas, his energy always captivating and inspiring. You could walk into his office to talk about a book project that we at Terreform had underway and walk out with instructions to contact a dozen different people about three more. Somehow amid this frenzy of activity, Michael always managed to maintain a laser-like focus on the Terreform mission of producing research to achieve more just, beautiful, and equitable cities. Somehow in this flood of ideas and instructions, proposals and counterproposals, Michael would always get the project done and the book (it always ended in a book!) printed.

Terreform was founded in 2005 as a place for connecting research, design, and critique on urgent urban questions and using that research in the public’s interest. UR (Urban Research), founded in 2015 as Terreform’s publishing imprint, was the vehicle to make ideas accessible and truly public. With Michael at the helm, both platforms produced an inordinate number of proposals, books, reports, articles, symposiums, and launches. All were self-initiated, and Michael, initiator that he was, has left all of us at Terreform with plenty more to do.

Most urgent is completing his—and Terreform’s—flagship project, New York City (Steady) State. The project’s central proposition is that the city can take responsibility for its ecological footprint. With New York City as his laboratory, Michael led several designers and social scientists in formulating designs and policies that could catalyze metabolic changes to critical infrastructural systems. The aim was to achieve a “steady state” of self-sufficiency within the city’s political boundaries. Ever the contrarian, Michael turned to steady state economics—a radical approach in a world addicted to growth and wilfully blind to its toxic consequences—to fashion an equally radical political vision of cities as central units for ensuring social and ecological justice.

NYC (Steady) State was conceived as a series of books focusing on food and waste systems, energy, and mobility as the four key systems drastically in need of redesigning. Just last month, Michael was making final edits to Homegrown, the first book in the series and one focusing on New York City’s food production, consumption cycles, and distribution systems. His devotion to the project was so fierce that even after being hospitalized he sent emails urging us to complete and publish the volume.

Beyond New York, projects were incubating in and about practically every corner of the world, all guided by students, friends, and admirers of Michael’s. Their ideas were seeded or sharpened in their encounters with Michael at Terreform’s 180 Varick Street office, where practically every workday ended with a visitor dropping by to say hello, being introduced to the crew, and sharing ideas over drinks. Terreform’s research projects have taken us to many places and brokered many friendships.

For instance, Terreform has a lively group of friends in Chicago hard at work on South Side Stories, a collective project that shines a light on activist groups in the South Side and their struggle to reposition the Obama Presidential Center from a magnet of gentrification to catalyst for equitable, evenly dispersed urban development. Set in another conflict zone, the Terreform/UR book Open Gaza will add to Michael’s already substantial contribution to the Palestinian struggle for social and spatial justice when it is published next month.

Our research projects, along with UR’s many internationally focused book projects, are primarily vehicles for showing how critique and design can speak the same language. For Michael, Terreform’s unique mission lay in developing an interdisciplinary dialogue that could be embraced by theorists, practitioners, and activists alike, and enable them to share new ways of looking at and imagining the world. Even as it hewed close to the standards of the university, Terreform sought to democratize these forms of knowledge beyond it by creating an accessible platform to address urgent issues in a timely and nimble fashion.

We know we can never fill the huge absence that Michael leaves us. We are nevertheless determined to carry on Michael’s enormous legacy, to complete the large number of projects that are already underway, and to continue the work of urban research for greater social justice, beauty, and equality in our cities.

Click here to learn how you can support Terreform. UR books are available for purchase here.

James Wines, artist and architect

The tragic loss of Michael Sorkin, as both a dear friend and premier voice for urban design on the international architecture scene, is still impossible for me to accept. At 87, I thought I would have been long gone before this, and so never anticipated experiencing the shock and despair I am feeling right now.

Michael’s work in design criticism, theory, history, and planning—particularly his efforts to shape the future of cityscapes—was inclusive and visionary; indeed, he was an indelible fixture in global thinking on these topics. He was one of those rare disciplinary figures whose voice was synonymous with the profession, so that it is impossible to think about the condition of architecture and urbanism today without Michael’s ideas as pivotal points of reference and beacons of wisdom. His absence is inconceivable.

While the endless fruits of his creativity will remain in museum and university archives to nourish future generations, an enormous part of the communicative value of Michael’s work was his participation in public dialogues. In this sense, he was like a great musical performer who made wonderful recordings; but the full measure of his talents was best experienced in concert format. Michael played both the revolutionary thinker and the consummate public speaker, a performance unmatched in architecture.

As friends, professional colleagues, and career-long skeptics concerning all manifestations of design orthodoxy, Michael and I had a bottomless reservoir of art and design issues to debate during our thirty-plus years of dialogue. In terms of primary emphasis, we were both committed to solutions for the public domain and how to best encourage interaction among people within cityscapes. I often used to comment, when introducing our appearances on symposia, that Michael took care of the larger issues in urban design while I followed up with solutions for the small stuff under people’s feet. As our discussions unfolded, this was invariably the scenario that played out: Michael would cover the master plans, civic strategies, economics, and infrastructure, and then I would insert ideas for the pedestrian amenities of walkways, seating, plazas, gardens, and play spaces. Whereas I could hold my own in the presentation of visual material, Michael’s verbal eloquence always stole the show. I can recall so many lectures and conferences where I would find myself so enthralled with Michael’s delivery that my own faculties failed when it came my turn to speak. He was the ultimate impossible-act-to-follow on any podium.

Michael and I had that kind of nurturing friendship where we could meet in an explosion of discourse on some hot topic, or just sit quietly at dinner and experience the reinforcing comfort of saying nothing. Of all Michael’s many talents, the pinnacle was his acerbic wit, with which he skewered the pomposities of our profession and politics of the day. Not only was his trenchant humor invariably on target, it was always articulated in such a way that inspired the opposition to re-think an issue.

It is especially ironic that Michael Sorkin—a major advocate of integrative cities and people interaction—passed away during a time of global pandemic, when millions of urban dwellers have retreated into protective isolation. For this reason, I want to end this tribute with a quote on his work from my 2000 book Green Architecture:

Michael Sorkin might appropriately be called a visionary with a heart. He has understood that, with the universal buzz about people living in cyberspace and communicating primarily through global wavelengths, this is already a reality and just another convenient set of tools that will soon be assimilated into the realm of routine. In this respect, computers are just like every other exotic technology that has nourished science fiction hyperbole and ended up as nostalgic curios in antique auctions. In designing for the future city, Sorkin has acknowledged that people are weary of looking at digital screens all day and sit-coms all night; so why on earth would they want their neighborhood to be another extension of virtual reality? The fact is that people need and value human interaction more than ever because of computer technology. In the Sorkin city, they walk, talk, sit on stoops, tend their gardens, and breathe cleaner air. Preserving this desirable reality is the basic goal of sustainability and the primary urban design challenge of the future.

Moshe Safdie, principal, Safdie Architects

For several decades, Michael Sorkin has been a unique voice in architecture. In a period of competing schools of thoughts, transitioning from one “-ism” to another, his critical voice was clear and constant, unwavering, with a focus on the impact of architecture on peoples’ lives and well-being; on the principles that must sustain urban life. He spoke about morals, values and ethics as others reviewed architecture as an ongoing fashion parade.

Michael’s commitment to the idea that architecture must be in the service of those for whom we build, led him to strip the discourse of architecture from jargon and private lingo; expressing ideas clearly and articulately to the general public. As a critic at The Village Voice, he reached many outside the profession. He became propagandist for architecture, both within the profession and to the public at large, expanding horizons of the impact of our built environment has on our planet.

Michael was a great and passionate teacher. I vividly remember his attendance at design reviews at the GSD, where sometimes faculty comments verge on the esoteric. Michael responded with surgical precision, getting to the essence of a design, and doing so in plain-talk. In his practice, both in Michael Sorkin Studio and Terreform, he was a prolific provocateur, embracing scales from small neighborhood parks to entire cities. The studio produced numerous proposals. Alas, not enough were realized, but the impact on the current generation is profound.

It is not often that we find, in one person, an architect, urban designer, educator, theorist, critic and writer. I will miss his voice, cut-off suddenly and untimely, at a time when it is most needed. I hope that the coming generation will embrace the professional ethic his life represents.

Deborah Berke, partner, Deborah Berke Partners, and dean of the Yale School of Architecture

Michael Sorkin was a great critic, inspired teacher, and a brilliant thinker. And happily for me, he was my friend. We would have a drink together once or twice a year and talk about New York. From old New York to the New York we loved to the New York we missed to the New York we hoped for in the future.

Michael was a searing and insightful critic, all the way back to his days at The Village Voice, as well as in his many books and in his more recent criticism for The Nation. He was also an insightful teacher—he taught at Yale twice, first in 1990 as the William B. and Charlotte Shepherd Davenport visiting professor, then in 1991 as the William Henry Bishop visiting professor. He brought these same teaching skills to his strong leadership as the director of the master of urban planning program at the Spitzer School of Architecture at City College (CCNY).

He was also one of the most learned and well-read people I’ve ever met. His interests were diverse and his memory was expansive. Michael argued for the greater good in every aspect of the built environment—from the smallest detail of a building to the largest gesture of a regional plan. He will be missed. His convictions, his voice, and his heart are irreplaceable.

Barry Bergdoll, Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

I can still rerun lines in my head verbatim from some of Michael’s Village Voice pieces—especially the ones I just couldn’t stop rereading while howling with laughter. His send-up of the Charlottesville Tapes was a true classic, a teddy bear to reach for in the most desperate moments of trying to survive postmodernism.

Michael was an arsonist to be sure, yet he also wanted to rebuild something of value and commitment in the place of pretension and posturing. He held out hope for all engaged in architecture to his last moments—as the bright moral light on the horizon that he was—that architecture could still be an instrument for building community.

When Reinhold Martin and I looked to launch our experimental Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream project in 2011, amid the ongoing foreclosure crisis, we turned to Michael, inviting him to participate in the opening panel discussion. He offered cogent analyses of our all-too vague brief as well as suggested lines of attack for making architecture that mattered. Along the way he also offered the audience gathered at MoMA PS1 and online a very moving description of his own upbringing in Hollin Hills, Northern Virginia. Hollin Hills was a place where Americans cultivated living together, Michael said, in language that starkly contrasts with the language of intolerance that has since invaded American life, virus-like. Ironically, I think he feared this virus more than the one that took him from us.

Michael left us right when we needed him most. With his lucid intelligence, sense of purpose, and biting satirical way of writing, he could cut away the flack even as he focused us on the essential. Nothing he wrote is dated, even if much of it was provoked by immediate events. To reread his pieces is to be in conversation with one of the most truly original and free-thinking minds of architecture. I can’t imagine how anyone will fill the gap, but the texts will continue to delight us and offer refreshing insights. (Think how he knew, for instance, to appreciate Breuer’s Whitney at the moment when fashionable opinion was dead-set against it.)

There are many ways to spend our evenings apart at the moment. I, for one, have found a superb tonic for these dark times: pour a glass of bourbon in Michael’s memory and prop open your favorite collection of his writings. We will miss you for years and years to come, Michael.

Vanessa Keith, principal, StudioTEKA Design

When I came to New York City as a young architect 20 years ago, I was in search of a mentor. Coming from a fine arts background, I wanted someone who I felt was a truly great mind, who I could learn from, and who would take me under their wing. So when I met Michael while I was working on a project for the Spitzer School of Architecture at CCNY, I felt an immediate affinity. He reminded me in some ways of my academic parents and their radical lefty friends who dreamed of a better world while working on their PhD dissertations. From there, I started teaching studio at CCNY in 2002, and being invited to Michael’s UD juries was definitely a high point. He was so innovative, and he always had the backs of everyday people who don’t always get to have their voices heard. He made us think critically and differently, and he didn’t shut down ideas just because they were coming from someone younger or less “educated.”

In 2007, Michael; Achva Stein, then head of CCNY’s landscape architecture program; David Leven, of LevenBetts and CCNY; and Ana Maria Duran, a good friend from grad school at Penn who was teaching at PUCE (Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Ecuador) in Quito, were doing a joint architecture, landscape, and urban design studio focused on a site in the Ecuadorian rainforest. Ana Maria invited me to lead a student charrette at the Quito Architecture Biennale, which I accepted. Once there, I received another invitation, this one to travel with the studio groups to Lago Agrio, taking Achva’s place. Again, I accepted, getting the yellow fever vaccine and some anti-malaria pills. Shivering and teeth chattering from a reaction to the injection, I jumped on the bus heading down the mountains. What a treat! We took trips up the river with local guides in canoes, avoided the areas marked “piranha,” and at a safer junction jumped into the muddy river water fully dressed in all our gear. The entire group stayed in the rainforest at a research station, saw butterflies in metamorphosis against the backdrop of oil installations, and had a jolly old time. Michael joked about making a calendar featuring scrappy Ecuadorian street dogs, the very antithesis of the Westminster Dog Show. He always rooted for the underdog, valuing the ingenuity and skills of local people and treating them with the utmost respect.

Michael helped so many people, and he was so generous with his time. He was always up for coming to Studioteka and playing the role of critic for whatever we were working on in our annual summer research project. That’s how my book, 2100: A Dystopian Utopia — The City After Climate Change for Terreform’s UR imprint, came to be. Several years of in-office juries, occasionally zinging (but usually hilarious and on-point) critiques, and edits followed, and the book came out in 2017. Since then, Michael and the team at Terreform have offered incredible guidance, support and enthusiasm, helping us to get the word out, and cheering me on through each book event, lecture, publication, and milestone.

More recently, we had our 2100 VR day at StudioTEKA and gave Michael, along with UR managing director Cecilia Fagel, their very first experience in virtual reality! They were dubious at first, but they were quickly among the converted. At one point in the VR tour, they were put on a plank changing a lightbulb hundreds of feet above the city, and in the end, they asked everyone to jump down. Michael demurred, Cecilia said yes, and we had to catch her!

Michael was a brilliant mind, a champion of the dispossessed, and someone who fought valiantly for a just, equitable, and environmentally sustainable future. He believed in cities, in the power of collective action, and that doing better was always possible. Now we must strive to carry on without him, and push hard for the better world he laid out for us in his work.

M. Christine Boyer, William R. Kenan, Jr. professor of architecture and urbanism, Princeton University School of Architecture

It is too soon to bid farewell to my friend and colleague Michael Sorkin, whom I knew since we were students together at MIT. The last time we saw each other, in late January, we simply hugged each other goodbye: he was due to fly to China, I to Athens. It is indeed a silent spring now that he is gone!

Yet his legacy lives on. He leaves a profound and lasting impact on public awareness, on architectural practice, on political commitment! His call to action remains.

Michael Sorkin was the conscience of architecture, a visionary change-maker, dedicated educator, engaged author, and imaginative designer. He never backed down from opposing points of view. Rather, he called us all to live better in the world, to mend the city of inequity and injustice. He helped us build solid relationships through his edited books, a forum he built for voices to rise up together in solidarity. He was truly the root from which sprung our dedication to a socially responsible architecture.

Michael’s pen brilliantly and humorously elevated the level of architectural and urban criticism into a new art. He was always writing for a better city yet to come. His concern was how to build a city of freedom, diversity, authenticity, participation, intimacy. Let his words speak!

“For me, writing has been the extension of architecture by other means both polemically and as fuel for my money pit of a studio. I write because I am an architect.” —Some Assembly Required (2001)

“Architecture cries out for a reinfusion of some sense of responsibility to human program as a generative basis for both its ideology and its formal and technological practice, but gets it less and less.” —Some Assembly Required (2001)

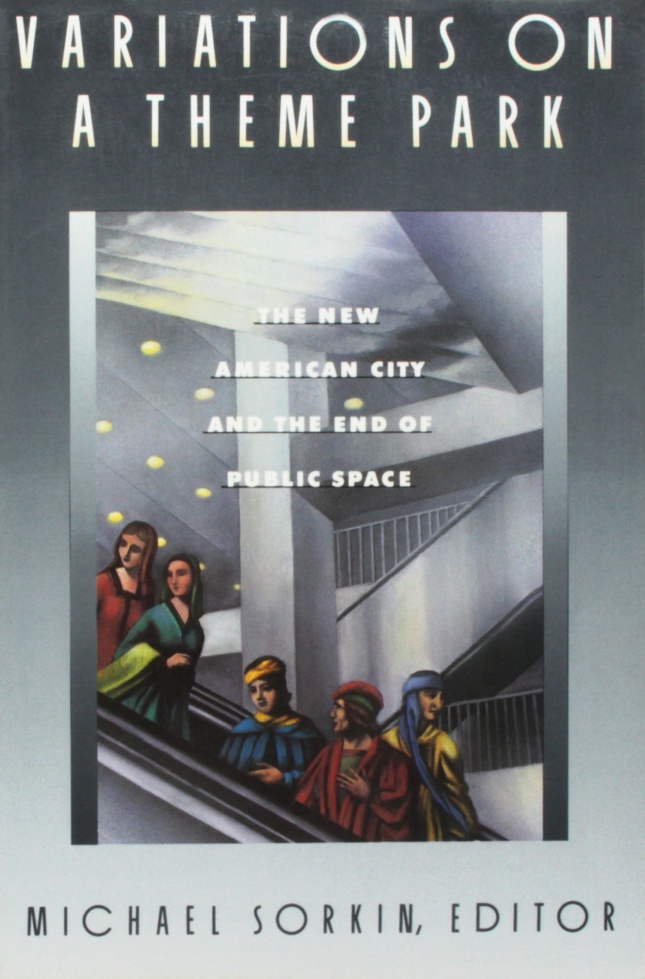

“[T]he new city is little more than a swarm of urban bits jettisoning a physical view of the whole; sacrificing the idea of the city as the site of community and human connection.”—Variations on a Theme Park (1991)

He pleaded for a return to a more authentic urbanity, “a city based on physical proximity and free movement and a sense that the city is our best expression of a desire for collectivity.” The goal was, and is, “to reclaim the city is the struggle of democracy itself.”

And it is a struggle over contending voices!

“[T]he City is both a place where all sorts of arrangements are possible, and the apparatus for harmonizing autonomy and propinquity./ Freedom, pleasure, convenience, beauty, commerce, and production are the reasons for the City.” —Local Code: The Constitution of a City at 42° N Latitude (1993)

Michael’s critical writings on the politics of architecture live on, be they about the utopian schemes for the World Trade Center or the reconstruction of New Orleans, or the engagement of Palestinian and Israeli voices in the future of Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. He wrote about the battle for freedom, global and local responsibility, the environment, even as he addressed the milieu of architecture, making appeals for inclusion, for connectivity, for sharing, and more.

In this silent spring of isolation that robs us of his voice, his pen, his friendship and humor, listen to the small murmurs arising, the tributes that come in from far and near. Witness his influence great and small. From the soil he has nourished with his commitment and action will spring forth—amid ongoing contestation—a better city. Listen to his call! This dear Michael, our Michael, is your enduring legacy.

Sharon Zukin, professor emerita of sociology, Brooklyn College and City University Graduate Center

Michael Sorkin was an architect’s writer and a writer’s architect. He had a brilliant wit, a ready command of politics, history, and principles of design, and a passionate commitment to social justice. He wrote in plain English and published prolifically. He scorned hypocrisy, shunned opportunists, and acted to build a better world.

Although he had peeves—venal real estate developers, corrupt politicians, celebrity architects, that tin-plated hustler Donald Trump—Michael wasn’t peevish. He could not tolerate intolerance. He was impatient with himself, but he was also a generous teacher, colleague, and friend. During all the years that I knew him (I want to write have known him), I never understood how he could travel so far, write so much, or launch so many projects with so many people and always bring them to completion. Yet his genius ranged most freely, and his rage was most keenly charged, when he wrote about ego and power in the city that he loved: New York.

I admired Michael as a writer before I knew him as either an architect or a friend. I had been a devoted reader of his architectural criticism in The Village Voice during the 1980s. At the time, New York was in transition, moving from widespread deprivation to Reaganite glamour, yuppie glitz, and localized gentrification, even as fiscal austerity penalized the Rust Belt of the outer boroughs and quarantined communities of color. Michael cut through the hype to the complicit collusion of the real estate industry and government agencies; I learned a lot from reading him. Although he and I walked the same streets—and lived in the same neighborhood, Greenwich Village—his streets were more layered than mine because he knew more, had a better eye, and directed his critiques with pinpoint clarity. Who could ever catch up with him?

The elegant essays that make up the book Twenty Minutes in Manhattan—shaped by the walk from his home to his office—are my favorites in Michael’s considerable oeuvre. He starts with the stairs in the Old Law tenement where he and Joan, his wife and life-partner, lived for many years. He recounts the difficulties he has had climbing those stairs, especially on crutches after surgery, and then segues into a brief but exact description of their construction. This leads him to reflect on other, grander stairs. The long, straight flights of stairs in late-nineteenth-century industrial buildings that formed a “tectonic loft vocabulary” within the cultural syntax of New York. The elegant double staircases in the Château de Blois. The capacious stairs in the MIT dorm designed by Alvar Aalto, made wide so students would stop to talk to each other. Long before Prada stores and tech and other “creative” offices sprouted them, Michael had already taken the measure of a staircase’s possibilities.

“Architecture,” Michael drops into his conversation with the reader, “is produced at the intersection of art and property.” He exhumes the grid plan from its origins in the fifth century BC and relates it to the well-known scheme for laying out potential profit-bearing plots of land throughout Manhattan. Adopted in 1811, the grid not only set New York’s major money machine in motion but also set the course for its buildings, their heights and morphologies, and, yes, the stairs inside them. Which naturally makes him consider the pitch of the treads at the pyramids in Chichen Itza, only to return, once more, to his New York brownstone. This is—was—typical of Michael in writing as in casual conversation: erudition wrapped in humor that didn’t allow pomposity. Like Jane Jacobs, whom he greatly admired, and in whose honor he founded a lecture series at the Spitzer School of Architecture, he was a citizen of both the Village and the world. Like Jacobs, too, he saw the world in the city—but he also saw the city in the world.

Michael traveled constantly, giving lectures, pitching projects, taking his students on field trips to South Africa one year and to Cuba another. During his career, he wrote about many different cities. Wherever a community of architects, activists, and urban designers protested a plan, or struggled to turn back an egregious intrusion of monumentalism into a skyline or streetscape, Michael was there. You could count on him to fire broadsides, mobilize the troops, and persuade strangers to join him.

A few years ago, he persuaded me and others to write a short essay for a collective book he was putting together with people in Helsinki. This group strongly opposed the city government’s plan to contract with the Guggenheim Museum, then still in its expansionist phase, to build an expensive branch on a stretch of waterfront better left for public use. With these collaborators, Michael organized an anti-competition for design ideas and made us scholars into a jury. This mobilization, echoed by the popular opposition within Helsinki, helped to sink the Guggenheim plan. (Or, at least, it forced the city council to reveal its lack of funds.)

The last time I saw Michael, one month before he died, he asked me to come by his office. We talked about a Hungarian artist’s book project on luxury apartments for which we were both writing essays, dished some dirt about various cultural figures on the South Side of Chicago, and looked at the old photographs of Michael’s family on his shelves. We laughed about the double portrait of Joan and himself in front of the Taj Mahal that he had painted in Vietnam; Joan, considering it trashy, would not allow it in their home. Michael asked if I could recommend someone who could write about race and class in the neighborhoods near the University of Chicago for a book he was planning for his publishing house UR, and then asked if I would write something for yet another book he was planning, on smart cities. Although he was not in the best of health, a frailty that the virus would exploit, he still pushed forward. He was only prevented from taking another trip—to Africa—by the emerging blockade of travel restrictions.

My last email from Michael came one week later. He heard me talking about my new book on the radio and immediately sent me fan mail. This, too, was Michael: he acted on friendship. Almost twenty years ago, he and I edited a book of essays by New York urbanists where we tried to put together our abundant sorrows and critical thoughts about the World Trade Center. The words Michael wrote about the fallen Twin Towers surely apply to him. He was, in all respects, “the Everest of our urban Himalayas.”