2019 was another banner year for architectural biennials and triennials. With roots in world fairs and art biennials, the architecture –ennial as a circuit has been expanding on every shore: Chicago, Oslo, Grand Rapids, Seoul, Cleveland, Istanbul, and Columbus, Indiana, were but a few places that hosted architecture and design exhibitions last year. With so much variety in geography and content, it might be worth asking what, exactly, constitutes an –ennial. First, they are disciplinary events hosted outside of museums, and are temporary, itinerant, ever-evolving. Perhaps more importantly, –ennials, at least, those we will examine here, are performances trying to demonstrate why architecture and design matters to a variety of publics, how, as a discipline, architecture hurts and heals, and where the benefit to host cities might be in the future. Or maybe they are just expensive culture festivals manufactured to drive tourism and bolster civic “brand identity.” It’s complicated—and getting more complicated as we continue through the current pandemic.

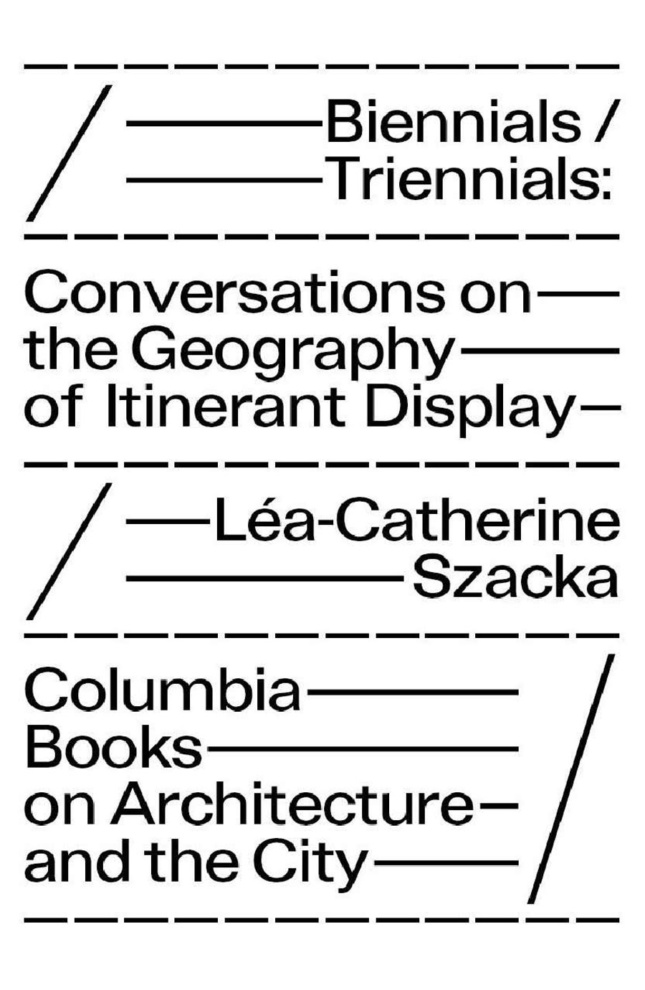

In her book Biennials/Triennials: Conversations on the Geography of Itinerant Display (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019), Léa-Catherine Szacka positions –ennials as agents for change operating within the architectural discipline. Over 175 pages, she works to define the “geography of itinerant display” that typifies the –ennial while exploring its “agencies” and effects. She approaches this task in two ways: by erecting (or improvising) a conceptual framework with which to better understand the –ennial phenomenon, and by engaging six of its leading exponents in a series of interviews.

Szacka highlights a number of milestones in the development of the –ennial, none as pivotal as establishment of the architecture sector of the Venice Biennale in 1979. The subsequent exhibition in 1980, with its indelible sense for pageantry, built to a kind of global explosion in events by the 1990s. Today, the geography of –ennials is indeed vast, with a program on every continent (yes, even Antarctica). Here in Columbus, Indiana, where we are surrounded by marvels of postwar modern architecture and design, we created Exhibit Columbus in 2016 to explore architecture, art, design, and community through alternating symposia and exhibitions. While we don’t consider Exhibit Columbus a typical –ennial, but rather a project that both investigates the design legacy of this place and presents new ways to engage and care for our community. The copies we have of Szacka’s little volume in the office are filled with Post-It Notes and marginalia; surely, others working in this arena—or those aspiring to—will be glad that the book is saddle stitch bound, as they’ll be flipping back through it for weeks and even in two-to-three years time, when constructing the next exhibition (or project). Architects, planners, and civic leaders should find equal value in Szacka’s study as a reflection on the discipline and practice of architecture, planning strategies, and the creation of city-wide events.

I, myself, view the book as a kind of exhibition in itself. A punchy preface by Martino Stierli, MoMA’s chief curator of architecture and design, directs the reader—or “visitor”—to Szacka’s excellent introduction, which, in turn, gives way to a timeline (de rigueur for any exhibition), leading to the main event—the interviews. On the way out you can glimpse the bibliography that underpins the whole enterprise, but which, according to Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, among the handful of curators Szacka interviews, no one will bother to consult (more on that later). And where the credits should be, there is instead a dazzling photographic array. Yes, there are 30 pages of color images culled from Instagram, beginning with “prehistory” (Aldo Rossi’s 1979 Teatro Del Mundo) and eventually crossing over into history (i.e. the launch and popularization of Instagram at the beginning of the 2010s). When it’s all over, you’ll probably spend a lot of time thumbing the pages of images and seeing how many of the Instagram usernames you recognize.

It would be easy to criticize the inclusion of Instagram, the same way that we critique each biennial or triennial. But Instagram is as much a part of the performance and response to any –ennial or exhibition today as a catalog, if not more so. Here in Indiana—deep in the Heartland—we know how important it is to have a digital presence that is clear, smart, and visible to folks who may never actually attend our symposium or visit our exhibition and remarkable small city. A smart Instagram account is a critical part of an event’s success, functioning as an exhibition listing, map, a repository for criticism and commentary, and time capsule all in one.

In the introduction to her book, Szacka takes a long view of the –ennial, beginning with the 1895 Prima Mostra Internazionale d’arte della città di Venezia. But the real work gets going as she sets up the connections between the –ennial paradigm and Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle (published in 1967, around the time when the professionalization of the “curators” first occurred). Debord bemoaned “a world dominated by entertainment events, and commercially driven tourism,” which certainly seems to sum up the –ennial rather well.

Architectural exhibitions are at once conceived as places of exploration, speculation, review, and even formulas for generating new knowledge. At the same time, they are directly tied to cultural tourism, civic boosterism, and urban redevelopment; in a word, capitalism. It isn’t always easy to grasp the particular goals of each –ennial, and certainly they are each created for different purposes.

Szacka acknowledges that her book is not a full-fledged, critical reassessment of the role of –ennials (and I agree such a reassessment is needed), but it nonetheless acts as a provocatory first step in this direction. She approaches the subject using three points of criteria: format, space, and content. These terms are explained in some detail along with a kind of preemptive conclusion that seems strangely placed, i.e. before the actual interviews. As a framing device, it is unclear, and besides, Szacka’s terms rarely inform the structure of the interviews.

What makes the book so accessible, then, is that one need not fully grasp, or accept, Szacka’s framework to enjoy the interviews, which are the real draw here. Her interviews sparkle with interest because of their candidness, variety, and complexity. Szacka has a long-standing stake in the historicization of –ennials (her previous monograph examined the events leading up to and including the 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale), and so she makes for an ideal interrogator. I often found myself just as interested in her questions as the answers of her interlocutors. All but one of the six interviews revolve around the logistical problem of curating a large-scale exhibition, yet they never grow stale or repetitive.

Nevertheless, I found the selection of interviewees to be somewhat narrow; for example, I would have also appreciated hearing from Beatrice Galilee and her shifting role from curating the Lisbon Triennale to working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and beyond. Indeed, some of the interviews seem more geared to insiders who possess a knowledge of which curator or theme appeared at this or that –ennial. Yet, in spite of these occasional moments, I never felt left out of the conversations.

While most interviewees reflect on their work with an uncommon candor, I was most drawn to Colomina and Wigley. Perhaps it was their brashness and honesty about their own work, or maybe it was their unblinkered take on the state of the field and their dismissal of the whole genre of writing that fills the pages of –ennial catalogs (“Nobody reads it”). Certainly, their criticisms of the shortsightedness of –ennials and their commissioners—vis-à-vis material and labor expenditures—are valid. Now more than ever, we need for –ennials to become stronger and smarter “disciplinary agents” in the field, whose interventions might cause us to consider our audiences and communities in new ways.

In this vein, Sarah Herda’s interview ends the book on an optimistic note, pushing curators and architects to believe in their ideas so firmly that they are willing to defend them even at the risk of the ideas collapsing in on themselves. This notion of risk taking is so very important to –ennials! If we are to use –ennials for bettering the profession, and therefore our cities, we need to create more spaces where risk taking and even failure can be rewarded.

Speaking for myself and my team at Exhibit Columbus, we have embraced the idea of experimentation and risk-taking. After the event’s first iteration in 2017, we moved our focus away from notions of commercialization in the design market to community and local benefits. In the subsequent 2019 edition, we tried to find ways for each of the installations to have deep connections to different communities throughout our small city of 55,000 citizens, and more widely, North America. At the same time, we leveraged the context of Columbus as a place in the middle of this country that deserves global attention. Our greatest risk is the nucleus of our whole project: That a place in Indiana has a history that matters to the future as much as it did to the past. We see it as a kind of model for others to understand and present cultural heritage for future generations without being nostalgic.

In her concluding remarks, Szacka poses a pressing question: Can –ennials act as spaces for activism? We think so here in Indiana. Here’s hoping that, pending the outcome of the pandemic, Szacka is able to continue her studies into the –ennial.

Richard McCoy is the Executive Director of Landmark Columbus Foundation, which produces Exhibit Columbus.