The Brooklyn Music School in Fort Greene hit a roadblock Tuesday in its plans to more than double in size when New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) questioned the design of the proposed expansion and declined to grant its approval.

Of the nine commissioners participating in the two-hour virtual public hearing, everyone but the chair voiced reservations about the scale and appropriateness of the 24-story building designed by the New York-based FXCollaborative.

The panel’s lack of support was a setback for the music school and project developer the Gotham Organization. Because the proposed construction site at 130 St. Felix Street (presentation viewable here) is part of the city’s Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Historic District, the development team needs approval from the preservation commission in order to obtain a building permit as well as zoning approval.

The chief sticking point for the school is that its proposed 20,000-square-foot addition would not be a low, freestanding structure comparable in height to existing townhouses on the other side of St. Felix Street. Instead, it would occupy the first two floors and basement of a 285-foot-high residential tower designed to contain about 120 condominiums above the school, including 35 units of Mandatory Inclusionary Housing for moderate-income homeowners.

Gotham executive vice president Bryan Kelly told the commission that his company purchased the site several years ago with the idea of making the school’s expansion part of a larger development.

Kelly said that the market-rate units would generate enough revenue to cover the cost of the affordable units, without requiring any public funding assistance. He added that tower has been designed to fit in with the area, in terms of its scale, colors, materials, and architectural vocabulary. “We believe it blends in with the old while creating a positive new addition to the neighborhood. We have focused on striking a balance with height and density, while creating a building with enough market-rate units to cross-subsidize the cost of building BMS’s space as well as approximately 35 MIH affordable homeownership units without any direct city housing subsidies.”

Kelly acknowledged that there has been “resistance” to the design from some area residents, including a contingent that would prefer to see no development at all blocking views of existing buildings in the area. But he said he believed “the gains for the greater good far outweigh the minimal impact upon the views of a select few.”

Founded in 1909 as a community school for the performing arts, the Brooklyn Music School is separate from the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which was founded in 1861 and occupies several buildings in the historic district. Gotham is a community developer that has created more than 30,000 residences, including an extensive portfolio of affordable housing.

The music school announced plans last year to work with Gotham to build an addition as part of a larger development on a vacant lot next to its current home. At the time of their announcement, the developers said they hoped to begin construction in 2021 and open in 2023.

According to its website, the school has 85 percent of the funds needed for its portion of the project and is raising the rest. Part of the money is expected to come from the sale of air rights above its current property.

Shelby Green, chair of the music school, told the commission that the school has more than 6,000 students who study a wide range of music, from hip hop to African drumming to opera. She said the majority of them are “below the poverty line” and receive instruction at reduced rates or no cost at all.

Green said the school has “long outgrown” its present facilities, which are housed in four converted townhouses on St. Felix Street built more than a century ago, and that the expansion will help the school continue to serve as an anchor for the cultural district.

The current facility at 126 St. Felix Street, with about 12,150 square feet of space, lacks “the trappings and infrastructure for modern arts instruction,” said Green. “The planned building will mean more than doubling the existing space [and] the installation of state-of-the-art equipment and room design,” including space for a digital music lab and more dance and rehearsal space for students.

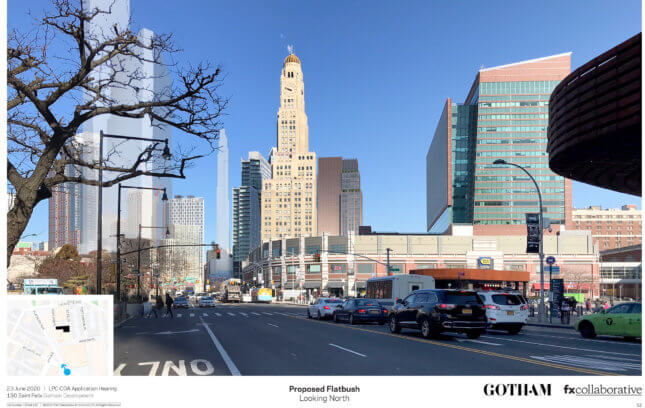

Daniel Kaplan, a senior partner of FXCollaborative, told the commission that the tower was designed to be part of an urban ensemble along with the Hanson Place Central United Church and the former Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower, a 41-story landmark that has been converted to condominiums and is now known as One Hanson Place.

Kaplan said the design team worked to create a contextual building that fills a gap in the streetscape and maintains the continuity of the street wall. He said the tower’s design is intended to make a transition in scale between the church and the bank tower and that its vocabulary is inspired by the Art Deco and neo-Romanesque style of the Williamsburgh bank tower, designed by Halsey, McCormack & Helmer.

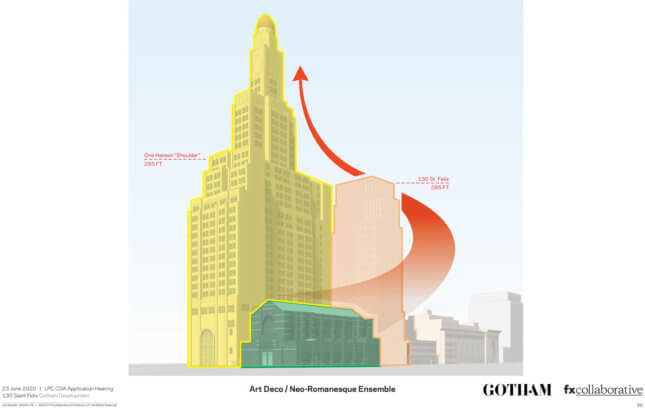

Kaplan pointed out a series of setbacks intended to “slenderize” the tower’s form as it rises and help separate it visually from the Williamsburgh bank tower, so the new building is read independently and not mistaken for an addition to One Hanson Place.

He said the exterior would be clad with wire-cut brick in eight different shades, transitioning from light to dark as they move up the side of the building to create an “ombre” effect. Additional materials include scalloped terra cotta spandrels, limestone at the base and painted metal for bulkheading near the top.

Kaplan added that they limited its height to 24 stories so the tower rises no higher than the “shoulders” of the Williamsburgh bank tower.

“We believe it’s scaled appropriately to the historic district,” he told the panel. “We believe that the tower is massed appropriately, with its vocabulary of Art Deco-inspired setbacks that are deployed to maintain the civic scale of St. Felix [Street] and also to expose the north end of One Hanson and create a pleasing taper on the skyline.“

According to Rich Stein, the commission’s intergovernmental and community affairs coordinator, the panel received about 100 letters or messages from people opposed to the design and about a dozen from supporters. Half-a-dozen opponents also called or Zoomed in to the meeting to tell the panel what they thought.

Opponent Charles Cohen said the commission decided in 2007 that a 17-story building wasn’t appropriate for the BAM historic district, and he believes that should ruling be seen as a precedent for St. Felix Street.

“Landmark hearings are about appropriateness, not about… tenancy,” he said. At 285 feet high, the St. Felix project ”is not appropriate architecturally, historically, or culturally. It is not appropriate within the historic district…The commission should reject this proposal in its entirety.”

Kelly Carroll, representing the Historic Districts Council, said the group’s public review committee found the design to be a “creative, attractive composition with a high-quality palette of materials. However, it is in the wrong place. It should be constructed outside of the Brooklyn Academy of Music Historic District. It appears shoehorned into a low-rise street next to an elegant collection of 1850s row houses. It is impossible for a building of this scale to ever have a natural urban relationship with them… We ask for the scale of this district to be preserved.”

Christabel Gough, a member of The Society for the Architecture of the City, said the Williamsburgh bank tower “changed the face of Brooklyn” when it rose in 1927 and the commission so far has protected it by preventing other tall buildings from rising nearby and obscuring views of it. To allow a 24-story building to be constructed now so close to the iconic 1927 tower “ruins any memory of that historic architectural drama so carefully preserved through years of bipartite landmark regulation,” Gough warned. “The applicant is proposing a building alien to its surroundings and antithetical to the most basic concepts of scale, style, and context in landmarks preservation.”

The opponents’ comments were balanced by testimony and letters from representatives of a number of religious, arts, and civic groups that support the project.

The list includes the Brooklyn Academy of Music; Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce; Downtown Brooklyn Partnership; Downtown Brooklyn Arts Alliance; New York Landmarks Conservancy; New York Building Congress, and the Association for a Better New York, and parents of students at the school. Many of the proponents said the tower is a worth building at least in part because it will contain affordable housing and will help the school expand.

Mark Silberman, legal counsel to the commission, told the panel members that the intended uses of the tower, while perhaps relevant to other city agencies, technically aren’t the preservation commission’s concern, according to city law. Silberman pointed out that the commission has been asked to approve a certificate of appropriateness for the project and its charge is relatively narrow: To determine whether the tower fits in with the historic district, regardless of what it will contain or what benefits it offers to the community.

“You need to be looking at the impact of this proposal—its scale, its massing, its materials, its location, all the usual architectural issues that you’ve dealt with” in the past, he said. The affordable housing units and new spaces for the music school, while important elements of the program, “are issues that are really not for us to decide.“

In their comments about the project, the commissioners focused on the height of the proposed tower, the extent to which the tower is set back from both St. Felix Street and Ashland Place, and the tower’s relationship to the historic Williamsburgh bank building.

Several panel members noted that the strength of the 1927 tower has always been that it can be seen in isolation from all angles, soaring above the street.

They said they were concerned that the new tower was too close to the older tower and that, despite the architects’ efforts, observers may be confused and think it’s an addition. They also questioned the relationship between the proposed high-rise and the four-story townhouses on the other side of St. Felix Street.

Panel member Michael Goldblum said he was struck by the two sets of conflicting opinions voiced by the general public.

“The people who spoke in favor mostly were supporting the project because of its program, whether that’s the school or low-income housing, and those who were opposing it were doing so from the point of view of appropriateness,” he observed. “I certainly share the goal of the project… but that is not Landmarks’ direct mandate, to weigh that against appropriateness.”

Goldblum said he believes an argument can be made for putting a “high-rise element somewhere” in the area, “but “I think that putting it on this block fails the most basic test of appropriateness in terms of urban scale. I don’t think that we would naturally feel that a high-rise building on this block would be appropriate in the abstract.”

Goldblum suggested that the project’s “laudable civic goals” might be realized by shifting the tower away from St. Felix Street and closer to Ashland Place. But he said he wouldn’t want the new tower to look as if it was an appendage of the bank building. “You want it to be friendly with it, but it should not look like an addition.”

Panel member Michael Devonshire said he also felt that the tower is in the wrong location. “It’s the placing of the mass that’s objectionable to me. The massing should be on the other side of this [block] so that the St. Felix scale is maintained.”

Panel member Jeanne Lutfy said she thinks the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower is Brooklyn’s equivalent of the Empire State Building, and the proposed tower shouldn’t try to rival it in any way.

As proposed, “It’s too tall for the street and it’s too tall with respect to this landmark building,” said Lufty. “It shouldn’t be rising up to the shoulder. It shouldn’t in any way compete with or get in the way of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Building.”

“The whole project has to be reduced in scale,” said panel member Everardo Jefferson.

At the end of the discussion, chair Sarah Carroll said the panel would not take a vote on the proposal because it was clear the commissioners wouldn’t approve a certificate of appropriateness for the design they saw. Instead, she invited the development team members to “restudy” their proposal and come to a future meeting with a design that responds to the panel’s comments.