If our communities are ever going to reopen the economy safely during the COVID-19 pandemic, they need to find more ways to keep people apart and to make better use of outdoor space.

That’s the premise behind Design for Distancing, a planning initiative in Baltimore that has brought architects and public health experts together to develop tactical solutions for modifying city streets and sidewalks so they work better for the restaurants, stores, and services that are seeking to reopen after the long government-imposed lockdown.

On Monday, June 29, Baltimore Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young and others released the “Design for Distancing Ideas Guidebook,” a free online resource filled with strategies for bringing life back to public spaces while still complying with public guidelines for social distancing. Among the contributors were some of the region’s most respected design firms, including Ziger/Snead Architects, Ayers Saint Gross; PI.KL Studio, and Quinn Evans.

“Here in Baltimore and around the world, streets, sidewalks and stoops are important gathering places, and in many ways the intersection of our lives,” Mayor Young wrote in the online publication. “Recapturing these areas is critical to our reopening and economic recovery, but public health must remain at the forefront of every move we make.”

The mayor noted that the solutions in the guidebook are meant to be carried out not only in his city but around the world. He called the compilation of ideas “Baltimore’s gift to the global community.”

The guidebook is a joint effort of Young’s office, the quasipublic Baltimore Development Corporation (BDC), the nonprofit Neighborhood Design Center (NDC), and working with experts from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Sensing that restaurants and other businesses would need guidance for reopening after Governor Larry Hogan shut down most everything in mid-March to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the BDC and the NDC launched an ideas competition asking entrants to suggest ways to bring people back to traditional commercial districts while adhering to new guidelines for social distancing and hand washing.

A specific site for the competition was not given and entrants were asked to come up with design ideas that could be executed in a variety of locations. The emphasis was on finding ways to make better use of public spaces located near existing businesses, from restaurants to book stores to barber shops, at a time when people need more space for social distancing.

The competition drew 162 entries, ranging from hand-drawn sketches by grade school students to renderings from established design firms. Some solutions required that an entire street be closed; in others, the designers suggested taking over a parking lane or not using the street at all. Many used corners or vacant lots.

Instead of selecting a Grand Prize winner, the judges named 10 finalists, representing a range of urban interventions. Each received a $5000 stipend and their submissions have all been included in the guidebook along with a link to the others online.

The concepts can all be viewed online at https://www.designfordistancing.org/. The finalists were:

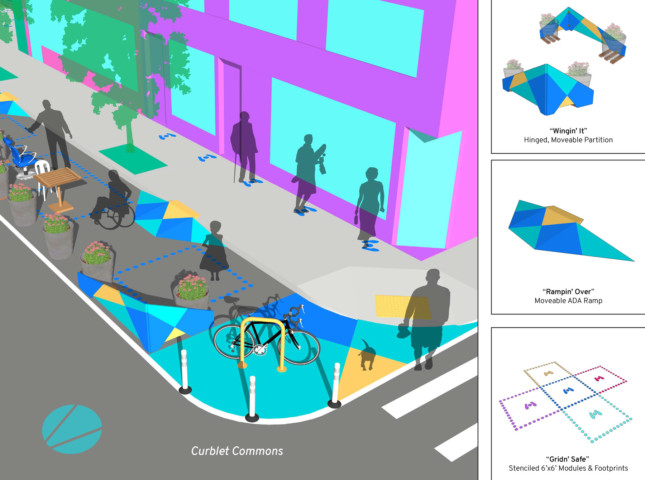

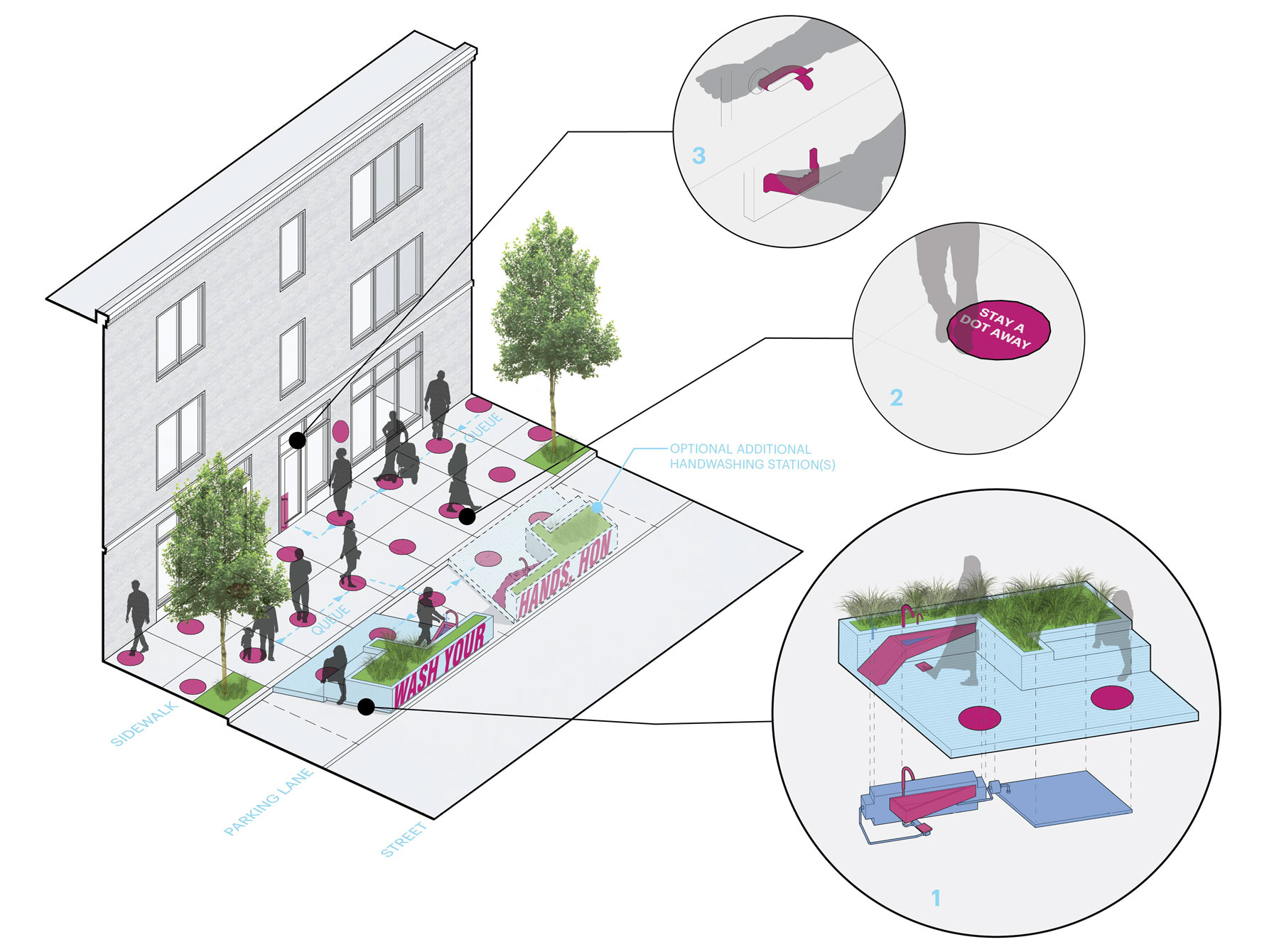

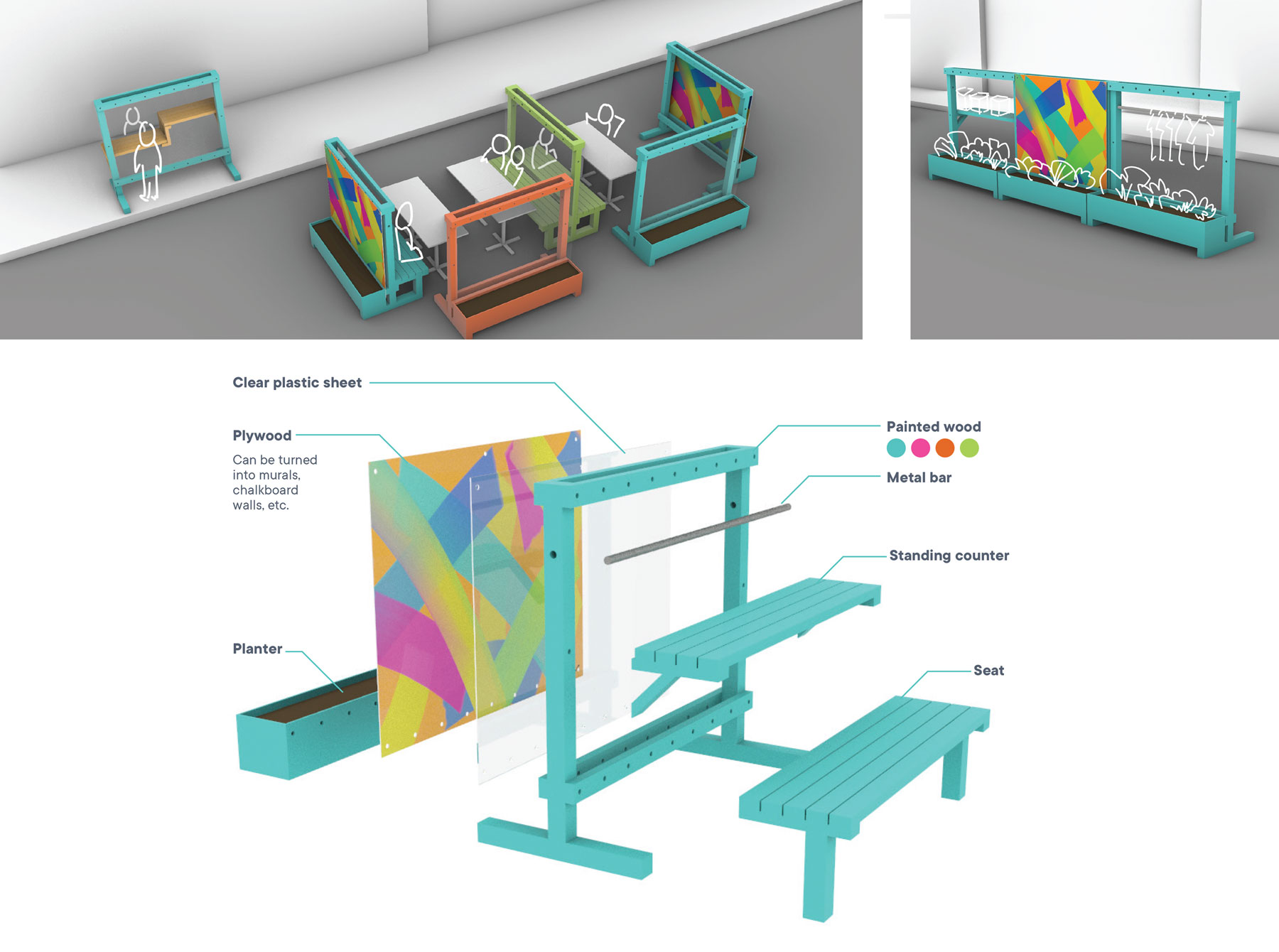

“Curblet Common” by Graham Coreil-Allen of Graham Projects; “Organizing the Street” by EDSA (Craig Stoner, Terri Wu); “Space Frame” by Zoe Roane Hopkins; “Hygiene, Hon” by Ziger|Snead Architects (Doug Bothner, Jeremy Chinnis, Cyrus Lee, Kelly Danz), and “The Food Court” by Department Design Office (Maggie Tsang, Isaac Stein).

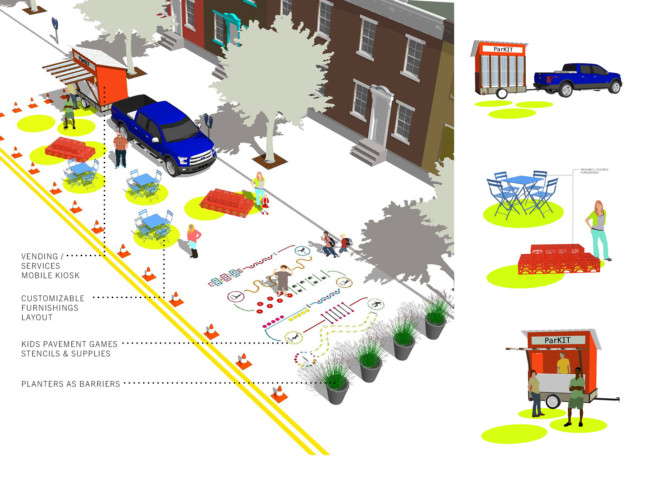

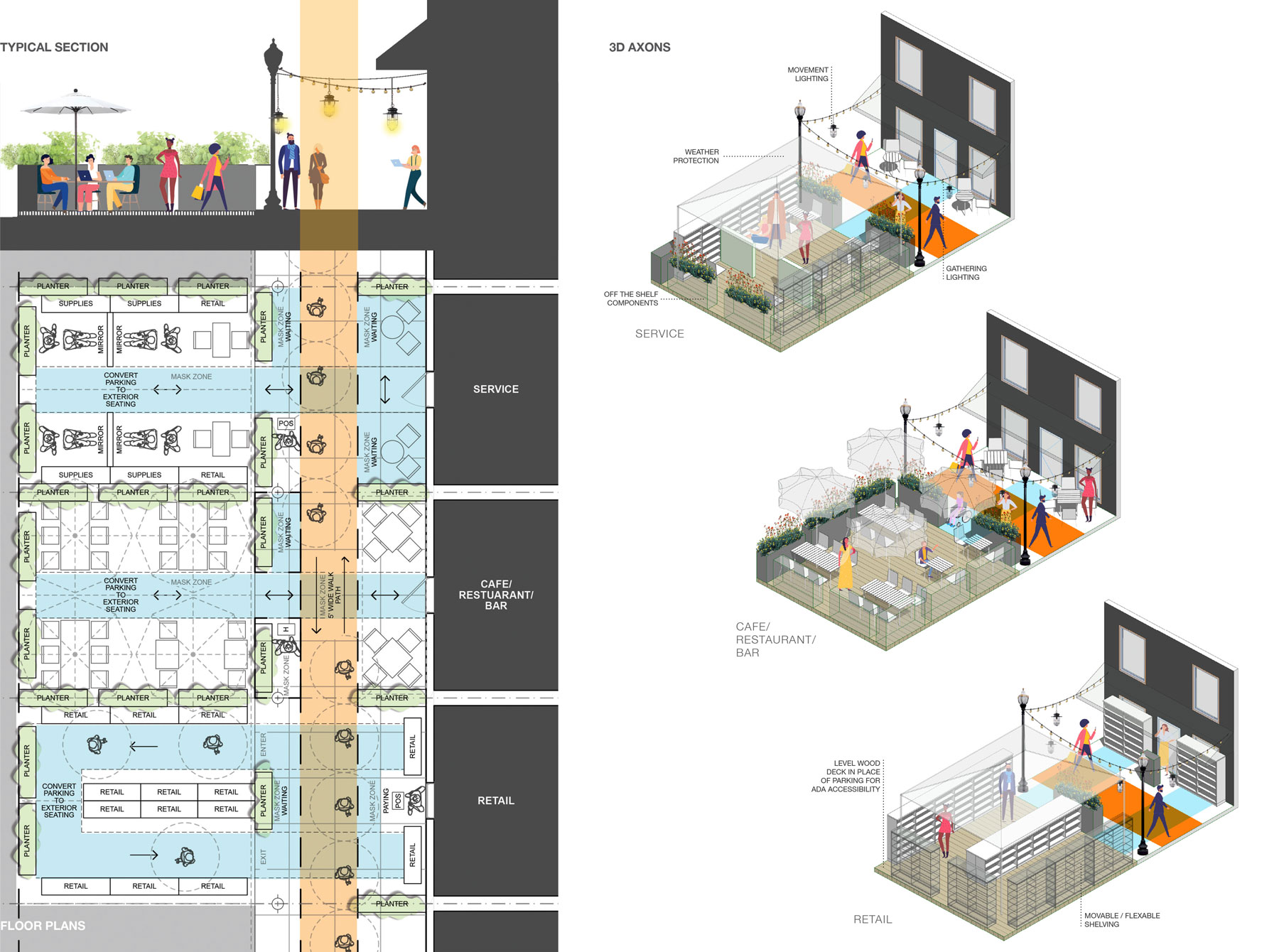

“Make ApART” by Quinn Evans (Ethan Marchant, Steve Schwenk); “inFRONT of House” by PI.KL (Pavlina Ilieva, Kuo Pao Lian, Brian Baksa, Esther Cho); “ParKIT” by Ayers Saint Gross (Abby Thomas, Michael McGrain, Connor Price); “Micro District” by Yard & Company and &Access. (Joe Nickol, Kevin Wright, Bobby Boone), and “Find Your Tropical Island” by Christopher Odusanya.

In addition to the guidebook, the city has a second component of its Design for Distancing initiative in which 17 design-build teams will propose and execute site-specific solutions for locations around Baltimore.

The design-build teams have been matched with their districts, and the city has budgeted $1.5 million for design and construction. Work is expected to start in early July and take several weeks to complete. The completed projects will be treated as pop-up environments and are expected to remain in place until the fall when temperatures start getting too cold for people to want to stay outdoors.

Jennifer Goold, executive director of the Neighborhood Design Center, said many of the final Design for Distancing proposals had common characteristics.

“The ones that really stood out felt like spaces you wanted to be in, while also meeting the very stringent guidelines that the public health teams were looking at,” said Goold. “They felt like places that you could relate to… You could imagine yourself there. They felt cheerful and like good-quality public spaces, but they also allowed you to keep that physical distance that’s required right now.”

Another common trait, she added, is that the proposals allowed for further modification, whether that’s addition or subtraction.

“They felt like you could achieve them within the budget that BDC was going to be offering to the community but that you could also take one or two good ideas from there and do it yourself. if you had, say, far less money or if you wanted to really take it further and invest in even higher quality and more permanent materials. They were ideas that you could use to improve a public space forever. They felt scalable in that way.

“They were the kind of interventions that many of us had hoped to see in Baltimore for a long time, even outside of COVID-19,” said Goold. “They would allow us to try some things in our city neighborhoods that we’ve wanted to try for quite some time but haven’t necessarily had the city infrastructure in place to be able to.”

Ultimately, she said, temporary changes that come out of an ideas competition have the potential to lead to more permanent improvements in the cityscape, if people like what they see initially, because they show what’s possible.

“This summer will probably feel a little more provisional,” she said. “But if we change our expectations and have positive experiences, then you could go to the next level with a real infrastructure. You’re not going to get real, permanent infrastructure in that $30,000-to-$75,000 range, but you are going to be able to occupy space within that price range and see if we actually enjoy being out in the city rather than sitting behind that plate glass wall.”

“It is definitely experimental right now,” she continued. “We’re doing it out of necessity because we have to, because we need to keep people safe and healthy. But I think it is an opportunity to learn more about how we might like to behave in the city.”

Goold explained that the immediate goal of the Design for Distancing initiative was to assist people coming out of lockdown and help small businesses stay open. But beyond that, she said, it can also be a learning experience that leads to lasting changes in the way people act in and make use of the public realm. The designs proposed here could also serve as a jumping-off point for other cities looking into reopening strategies.