In a preservation story that elicits some slight geographic whiplash, a real estate development firm based in Sonoma, California, has put out a call for Black architects and interior designers to collaborate on a project located well over 2,000 miles away that entails the restoration and reimagining of the Excelsior Club, a once-thriving civic and social hub of African-American life in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Said developer, Kenwood Investments, is hoping to assemble a “dream team” over the next two months that will “develop concepts” to help to revive the Art Moderne property, which despite its storied place in the annals of Charlotte history, has been closed for several years and is in serious disrepair. One assembled, the team will work alongside Darrell J. Williams, the owner and founding partner of award-winning, Charlotte-based multidisciplinary design firm Neighboring Concepts.

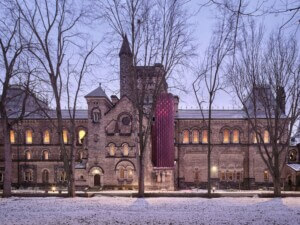

Established in 1944 by country club bartender-turned-nightclub impresario and businessman Jimmie McKee as a members-only hotspot for the upper echelons of Charlotte’s Black community, the Excelsior Club—a “cultural and political lodestar”per Charlotte Magazine—was shuttered in 2016 and, in the years since, has fallen into an even deeper state of decay. The foreclosed building was subsequently threatened with demolition and appeared on the 2019 edition of National Trust for Historic Preservation’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places List.

“Losing this property, with the history and uniqueness that it has—it would be noticed,” Michael Sullivan, a local realtor and co-founder of the preservation group Preserve Mecklenburg told the National Trust last year. “We’ve lost so many relics of our past, and I think the African American community in particular [has suffered].”

After multiple failed real estate deals last year hinted toward a gloomy end for the storied club, Kenwood Investments, perhaps best known for its involvement with the SOM-masterplanned redevelopment of San Francisco’s Treasure Island, successfully closed on the property earlier this year with plans to revive it as an entertainment/social venue featuring live music and art. Kenwood, which received local taxpayer-provided funding after closing the $1.35 million deal, also wants to add a boutique hotel to the property. As reported by WCCB Charlotte late last year, the funds will be expressly used to preserve or replicate the club’s iconic streamline facade, ideally the former. Some officials, however, have expressed concern about the likelihood of that considering the advanced state of deterioration the building is in.

Built along Beatties Ford Road in 1910 as a private home before McKee entered the picture and transformed it into one of the most, if not the most, prominent social clubs for Black Americans in the Southeast, the Excelsior has changed ownership a small handful of times over the years since McKee’s death in 1985. Carla Cunningham, a State Representative and widow/legislative successor of the owner from 1988 to 2006, Rep. William “Pete” Cunningham, inherited the club a decade after her late husband sold it to a friend. After obtaining the property, Carla Cunningham swiftly closed it due to the high costs of upkeep and later foreclosed on it. (For additional context, Pete Cunningham’s daughter, Khristina Alexandria Cunningham, wrote a June 2019 op-ed piece for Q City Metro, stressing the club’s historic importance and tracking its turbulent recent history.)

Designated as a historic landmark by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Commission in 1986, the Excelsior Club was a place to mingle, let loose, make connections, and seek refuge during an era when such establishments for Black North Carolinians simply didn’t exist. Listed in the Green Book, the Excelsior hosted musicians such as Louis Armstrong, James Brown, and Nat King Cole in its early years. Bill Clinton even paid his respects, making the club a pit stop during his 1992 presidential campaign.

“Jimmie McKee was early visionary in protecting and providing equal opportunities for African Americans,” said Kenwood CEO Darius Anderson in a statement. “For more than 70 years, it was the place to be for Black professionals, artists, and politicians thinking about running of office. I fell in love with its amazing history and look forward to restoring this for the people of Charlotte and our nation.”