On May 25, 2020, 46-year-old George Floyd died on a sidewalk while in the custody of the Minneapolis Police. This was only the latest event in a chain of police killings of Black citizens over decades, one that sparked protests across the country and around the world.

From the ground here in Minneapolis, the initial news of Floyd’s killing seemed like more of the same. We’ve lived for years with a militarized police force that is largely white, often incompetent, and beholden to its union chapter, the Minneapolis Police Federation. Lieutenant Bob Kroll, the chapter’s elected president and Trump spokesman, is a bad boy cop straight out of Central Casting.

Roughly 1,500 buildings across Minneapolis and St. Paul were damaged or destroyed in the week of protests following Floyd’s murder. Although generally under-reported, the vast majority of the damaging arson incidents were instigated by outside white agitators.

Perhaps, because of the clarity and cruelty of the videos recording Floyd’s death, the incident became a global tipping point. Reporters came from around the world and broadcast images of the burning Third Precinct police station along with the hollowed-out shells of stores.

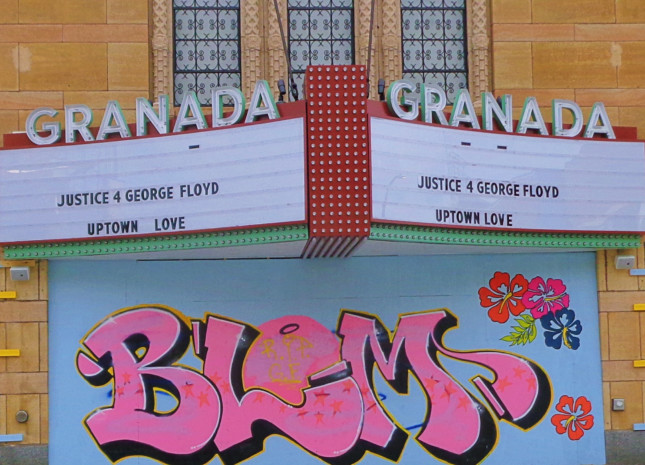

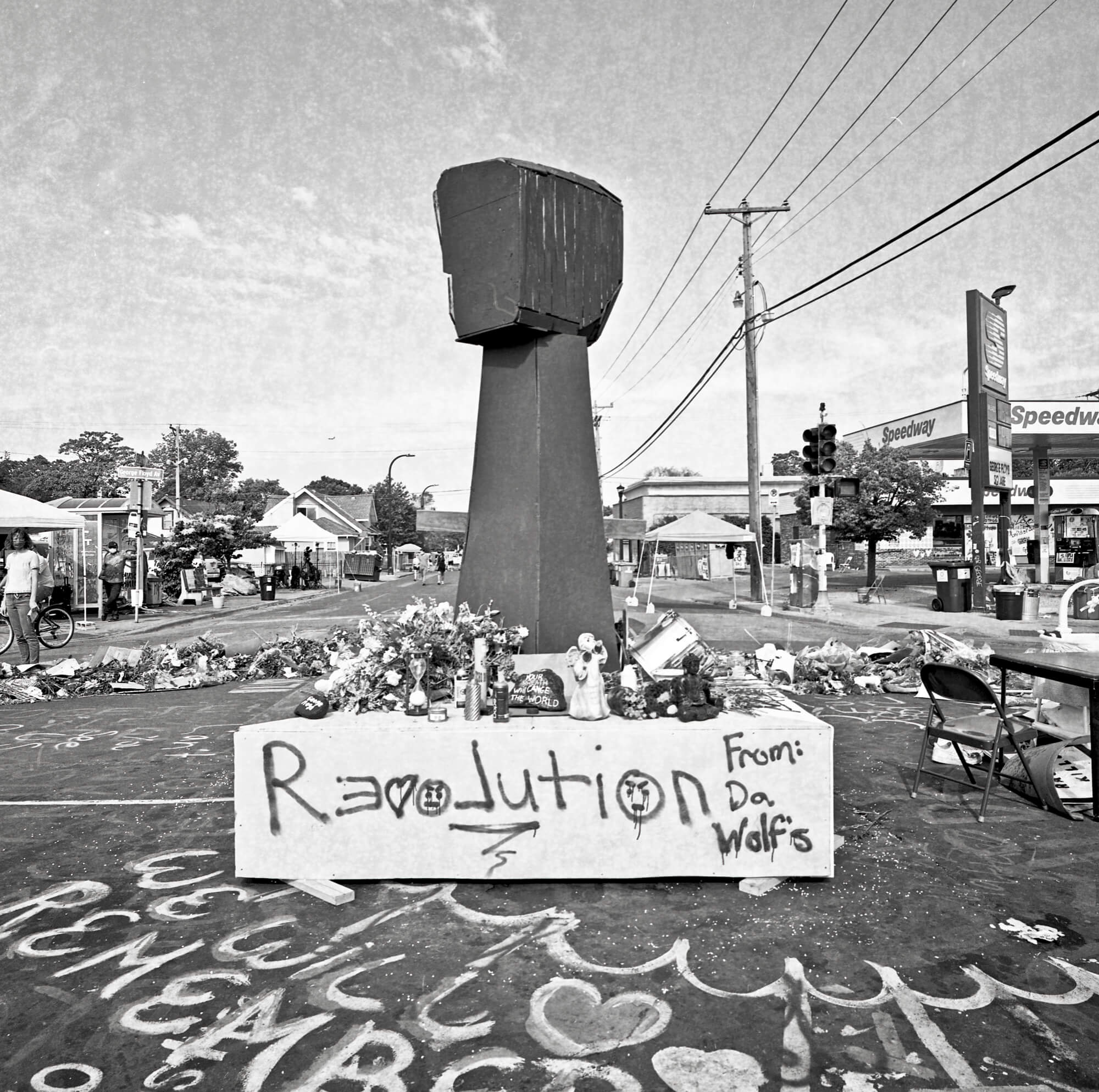

Much of the television coverage focused on the “loss of property” and the perceived threats of chaos. But the city residents who experienced these days and nights will long remember the outpouring of bold and colorful works of protest art that bloomed along the damaged streets.

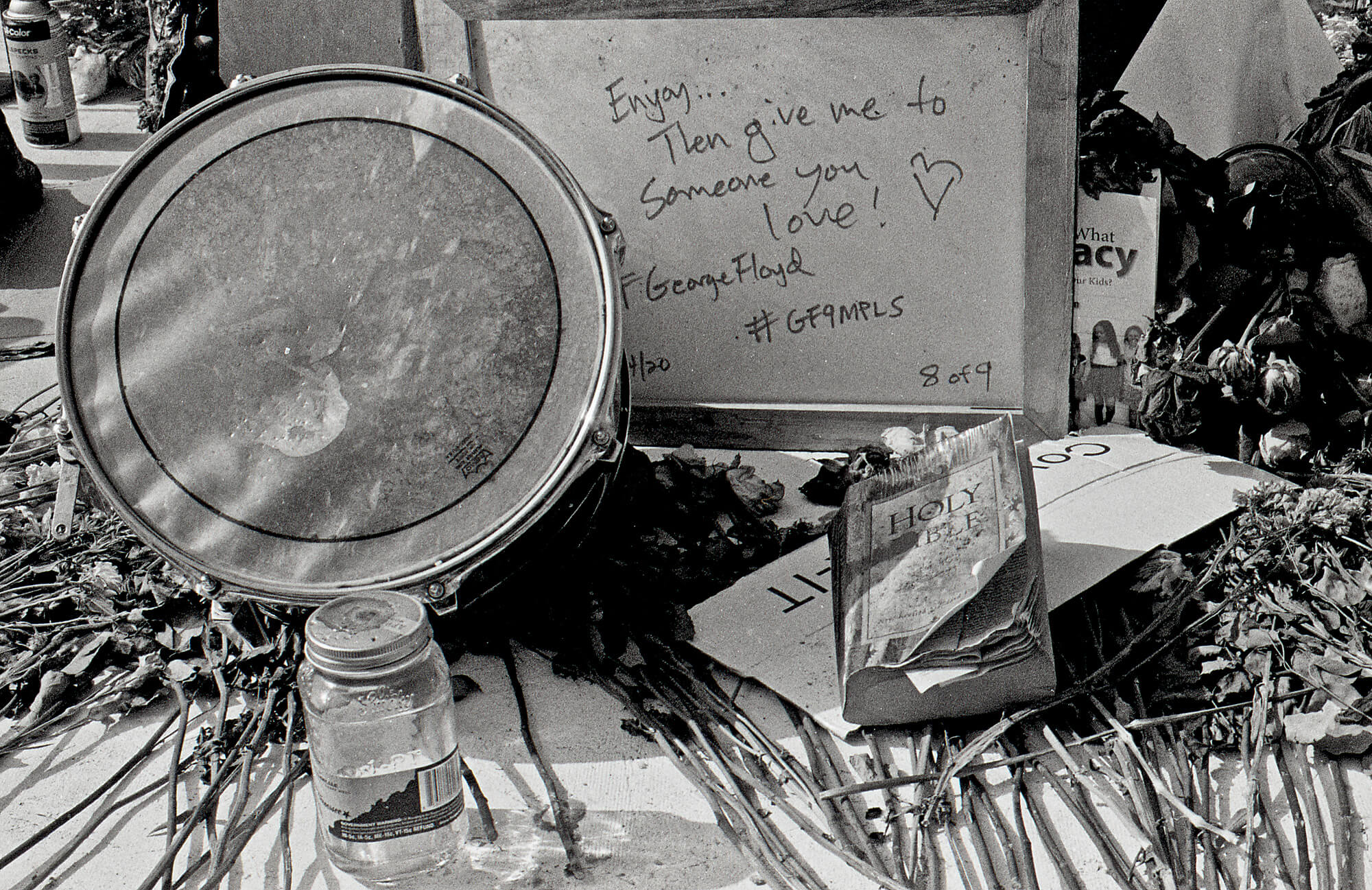

In the days after Floyd’s killing, you could see the employees of restaurants and shops coming outside to paint their boarded-up storefronts. High school art students painted many of the plywood window coverings in the Uptown area with depictions of other police victims and calls to “Say His Name”.

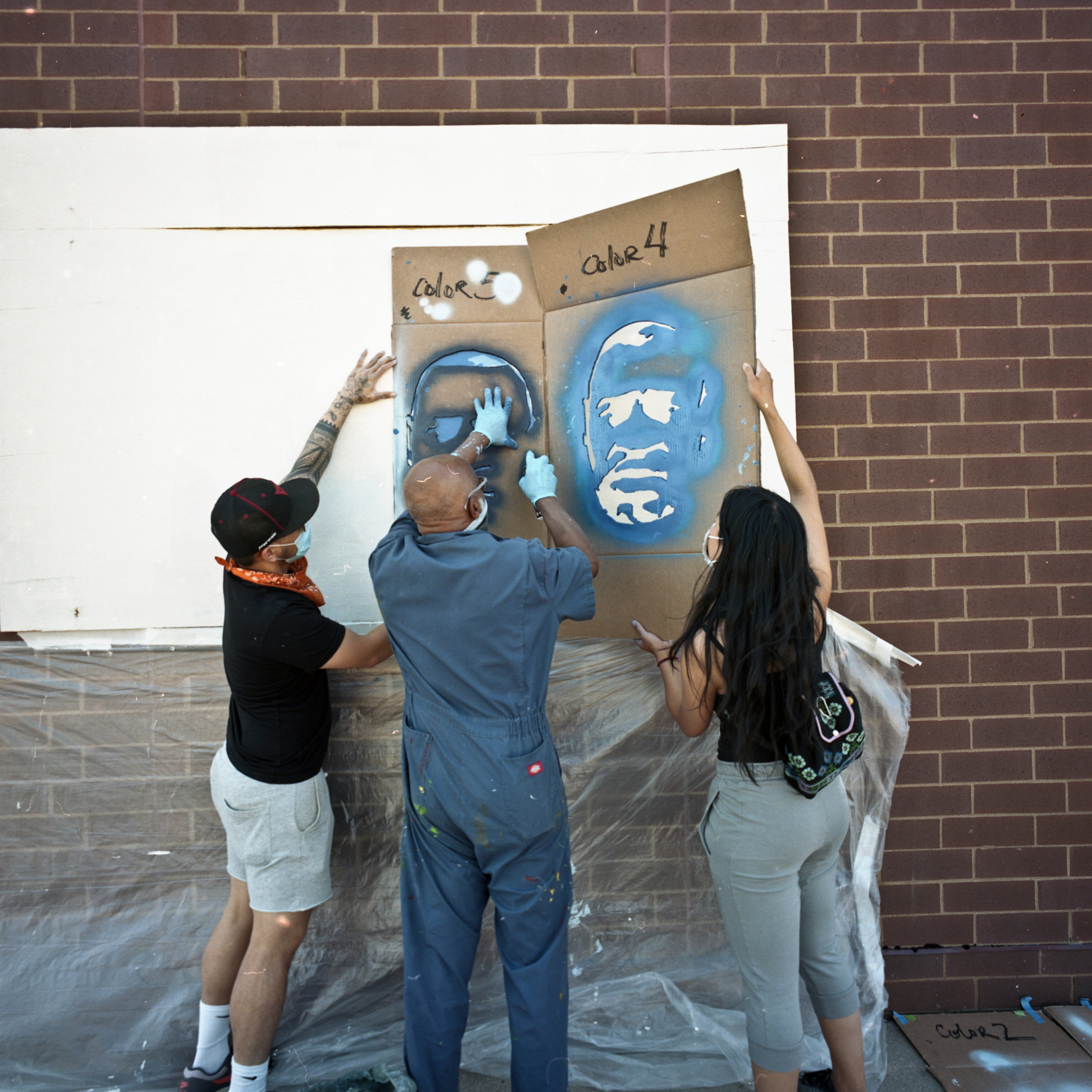

Verbally and visually George Floyd’s memory and name were everywhere. Local artist Seitu Jones created stencil portraits of Floyd that people could apply in their neighborhoods. He worked with members of the Gordon Parks High School in St. Paul to create a stencil installation.

Taken as a whole, these murals, stencils, portraits, paintings, graffiti scripts, and photographs are the most powerful grassroots public art that Minneapolis has ever seen. They grew into momentary streetscapes expressing the full range of emotions swirling at the moment. But none of this artistic outpouring was ever meant to be permanent.

Landscape Tourism

Shortly before Floyd’s death, I was invited to take part in planning a weekend of historic and contemporary landscape architecture tours in the Twin Cities slated for the summer of 2021. The event is part of an ongoing series of city tours sponsored by a national preservation organization for its members to visit. A book will be made about the tour sites and residents will be invited to attend.

From the start, I was skeptical about mostly limiting this cultural landscape event to landscape architecture and the vague discussion about how to include indigenous and minority stories. And then George Floyd was killed, and the city exploded.

In our first Zoom meeting after Floyd’s death and the protests, I suggested that this event had a global impact and that we had to include it somehow in our tour sites and stories. Or perhaps we should postpone the event itself.

Some members of the committee couldn’t see how landscapes of protest art could ever be interpreted in a design tour. One reason, of course, is that such street works are inherently temporary unlike most of the creations by recognized artists, architects, and landscape architects.

Others questioned why Floyd’s death and the social uprising were even relevant in a tour focused on historic landscape architecture.

Others argued that some works of protest art could be included in the tours if they become permanent—or are at least still up next summer. I pointed out that we have long, harsh winters here, and they will not be. That was never their intent.

The Limits of Mainstream Historic Preservation

I still feel guilty about being so contrarian. But this honest debate among well-meaning professionals tells me that our definitions of history and memory are important questions right now in the Twin Cities. For a moment, we were in the epicenter of a pivotal event destined to become a lasting chapter in American history, but next year, will any of the George Floyd memorials large or small be left?

Why does tour planning seem so complicated right now? One reason is that historic architectural and landscape preservation lack the tools to address structural racism and the protests that burst onto the scene in late May.

Historic preservation’s interpretive structure stems directly from 19th– century European practices in museum curation and art historiography. Over a century later, preservation discourse and guidelines still focus on typologies organizing artifacts and objects by predefined cultures of origin, artists, styles, and subjective judgments of artistic excellence. This is one of many reasons why, until very recently, we’ve had so little interpretation of Native American sites and long-erased stories. There are few indigenous buildings or cities left behind to collect, preserve, and classify.

Native American culture is still an “add-on” for many regional histories and preservation tours. Tribal cultures and histories are presented as disconnected from the design-focused story after white settlement arrives. The same holds true for the protest art that lined the streets here for weeks.

Creating a definitive tour of cultural landscapes in any city is a complex and moving target. Even significant design styles can be excluded when out of fashion. For example, mid-century modernism and its vernacular echoes in commercial architecture became tour-worthy only in the last few decades—after they were old enough to be “rediscovered”, increasingly rare, or under threat.

But what of the landmark events such as the recent George Floyd killing with few lasting physical traces? Paradigm-shifting events like this murder are major social plot points with long backstories but soon-forgotten footprints on the streets.

Making Critical Connections

More than ever, we need to question how our definitions of “cultural landscapes” limit our ability to understand their depth—how words can both constrict and open new possibilities for political and social critique.

Part of a new critical strategy is to find connections in the landscape that reach far beyond design, style, and aesthetics.

A case in point is how the Twin Cities metropolitan region was shaped by early streetcar lines, post-war freeways, and federal policies for housing and transportation. These projects and policies fueled the sprawling segregated metropolis that we have today.

The resulting regional gaps in school quality, access to jobs, healthcare, and concentrated poverty say much about why George Floyd was killed by a largely white police force. This history explains why over 91 percent of cops in the Minneapolis Police live outside the city. It explains why and where Floyd was killed.

In the cultural landscape history of the Twin Cities, landscape architecture and urban design play aesthetically important but relatively minor roles. The real story is much deeper. We need a richer sense of landscape change and history that reveals connections within seemingly disparate acts.

Economically and racially segregated regions like my own are the result of choices made over time. Even the most seemingly innocuous choices, such as focusing on high-style buildings and landscapes in our tours and narratives of design significance, have an impact on future understanding.

Especially now, in a time of a pandemic, recession, and social uprising, a heritage event focusing largely on designed historic landscapes casts a misleading impression about how this region was shaped over time. For me, such narrowly focused events, and the funding needed to support them, seem almost irrelevant given the bigger story that just happened.

There’s no question that cultural landscape tours and discourse should embrace landmarks of architecture and landscape design within their larger social contexts. The professional history of landscape architecture is replete with stories of brilliance and vision still relevant today. In the Twin Cities, the greatest design legacy may well be our vast and connected and park systems first envisioned by landscape architect Horace Cleveland in the late 19th century.

These parks and boulevards knit the two cities and their neighborhoods together. For a brief span of days, George Floyd’s death had the same effect. Although borne from anger and frustration, so much of the resulting protest art flashed a message of persistence and hope.

A month since Floyd’s death, my fear is that his memory is already fading, especially among suburban residents who largely saw what happened on television. Most Minnesotans probably never knew why there was so much internalized rage in Minneapolis that suddenly burst forth.

But this tragedy also became an invitation to expand our appreciation for the interwoven histories of cultural landscapes in our tours, writings, and how we teach the history of cities. One hopeful note is that some of the protest art may be sold or auctioned in support of communities of color in the Twin Cities. The temporary landscape will be broken up, but the artworks will take on a different kind of lasting value.

How can the design and preservation communities share these artworks and their messages long after they are gone? Can we move beyond the artifact to address the cultural landscapes that really matter now?

Frank Edgerton Martin is a landscape historian, architectural writer, and design journalist. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Philosophy from Vassar College and a Master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin, Madison in Cultural Landscape Preservation and Landscape History.

Throughout the 1990s he collaborated as a writer/historian with Chris Faust in the Suburban Documentation Project. They traveled through much of the Midwest and Northwest dsocumenting and studying technology parks, new housing developments, and ephemeral vernacular commercial design.

Martin served for many years as a regular contributor to Landscape Architecture magazine, covering projects across the country, design history, and campus planning. He currently serves as a regular architectural columnist for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune.

Chris Faust is mostly known for his large-scale images of vernacular landscapes. His work has been exhibited at and collected by the Walker Art Center, The Minneapolis Institute of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and other regional galleries. He has received McKnight, Graham, Bush and Minnesota State Arts Board Grants.

His ongoing projects include: extensive re-photographic study of the original Henry Peter Bosse (1844-1903) photographs of the Mississippi River from the 1880s, long-term documentation of extraction landscapes in the Bakken Oil Field in western North Dakota, and continuing photographic studies of night landscapes.

In 2007, he published a monograph of his work entitled Nocturnes though the University of Minnesota Press. He has appeared in the TPT production “Minnesota Originals”.