Black Lives Matter meets America’s Front Yard in a new “experiential installation” on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., that’s designed to make visitors think about systemic racism in the United States.

The temporary, cube-like structure, Society’s Cage, made its debut on August 28, after several weeks of construction. A cross between an open-air pavilion and a freestanding cage, it was conceived and designed by a team of black architects from the Washington, D.C., office of SmithGroup, one of the designers of the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall.

According to its designers, Society’s Cage is both a sculpture and an exhibit that was created to call attention to “the historic forces of racialized state violence” in the United States, and it was created in the aftermath of the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor murders “as our society reckons with institutional racism and white supremacy.”

The architects say the pavilion is meant to educate visitors and function as a sanctuary to reflect, record, and share personal thoughts, while also evoking prisons where Black Americans were incarcerated. They say it was “conceived in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement as a mechanism for building empathy and healing.”

The National Mall is the most-visited property owned by the National Park Service, an agency of the federal government. Surrounded by monuments and museums, it is a common ground where the past, present, and future come together, a stage where celebrations take place and people gather to protest. It has been called America’s Front Yard; it’s not normal to find a cage there.

Measuring 15-feet-by-15-feet-by-15 feet, the pavilion was erected to coincide with the “Get Off Our Necks” Commitment March on Washington that was organized by the National Action Network. The March took place on August 28, the 57th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I have a dream’ speech. Society’s Cage will be open for the public to visit through September 12, after the installation proved so popular that the designers decided to extend its stay. The closest intersection is 12th Street and Madison Drive N. W.

Dayton Schroeter and Julian Arrington led the design team for SmithGroup. They were assisted by designers Monteil Crawley, Ivan O’Garro, and Julieta Guillermet.

The name Society’s Cage refers to “the societal constraints that limit the prosperity of the Black community,” said Arrington, an architectural designer with SmithGroup. “The pavilion creates an experience to help visitors understand and acknowledge these impacts of racism and be moved to create change.”

Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old African-American emergency medical technician, was fatally shot in her own apartment by plainclothes police officers in Louisville, Kentucky, who were executing a no-knock search warrant on March 13, looking for drugs. Gunfire was exchanged between the officers and Taylor’s boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, who said he thought the officers were intruders. Taylor was shot at least eight times and was pronounced dead at the scene. No drugs were found in the apartment.

George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, was killed on May 25 in Minneapolis during an arrest for allegedly using a counterfeit bill. Floyd died after a police officer, Derek Chauvin, put his knee on his neck for 8minutes and 46 seconds. Two autopsies found Floyd’s death to be a homicide. The action triggered weeks of protests in the United States and beyond.

In an interview, the architects said they designed Society’s Cage to be a fact-based installation that would help place recent victims killed by police, including Floyd and Taylor, in the context of what they see as a 400-plus year continuum of racialized state violence in the United States.

“It’s taking something very ugly and rendering it in a beautiful way,” Schroeter said. “Racism is an ugly thing. It’s an ugly phenomenon. What we tried to do, to the best of our abilities, is put it in a form that can sort of help communicate that ugliness, if you will, in a way that people can appreciate it and see it for what it is.”

What people get out of it will depend on what they bring to it, he added.

“It depends on the perspective. To some, this experience and process is a reckoning. For some, it’s a contemplative experience. It’s a reflective experience. It just depends on your frame of reference. But the beauty of it is that it has a universal appeal, no matter what your political affiliation or experiences are in life. It’s not our opinion. It’s a fact-based installation in many regards. We’ve sort of removed ourselves from it, as far as the politics of it. We’re just giving you sort of the raw truth.”

Arrington said SmithGroup took action because some of the firm’s Black employees felt strongly about the deaths and wanted to use their “craft” to do something about it. “We have a strong collective of people that are very passionate about the subject, and we wanted to do something in solidarity with Black Lives Matter.”

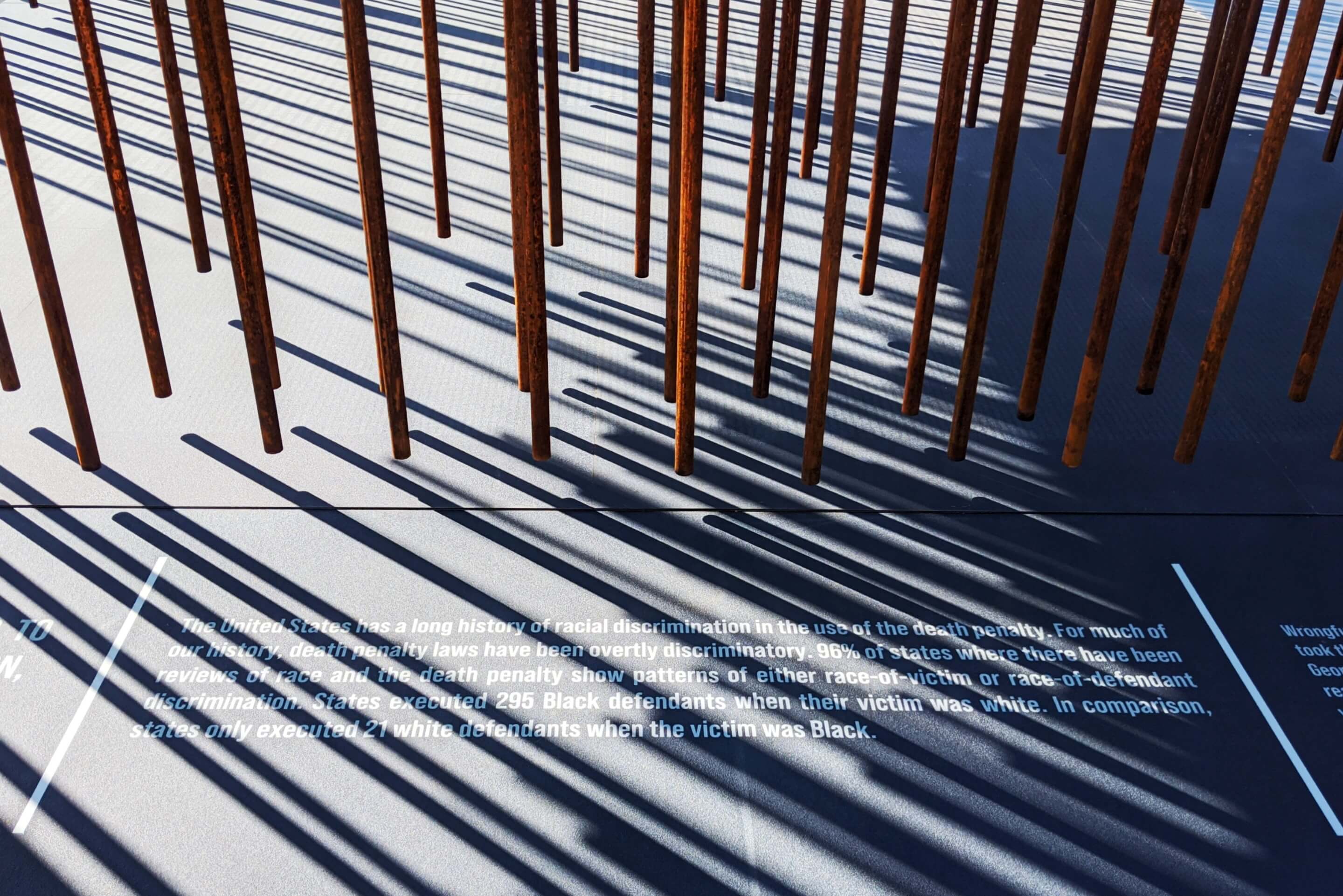

A visit starts by walking around the outside of the pavilion, which is defined by nearly 500 weathered steel bars that hang from a steel-plate ceiling and form a perfect cube atop a raised 15-foot square platform.

On the metal apron around the pavilion is “educational content, ”words and statistics that introduce four themes the designers say are the primary institutional structures of anti-Black state violence. The themes are racist lynchings; police terrorism; mass incarceration, and capital punishment. Even the bars that define the cube represent data about racial imbalances over the years.

The exterior of the pavilion is intended to serve a primarily educational role, while the interior has more of an “emotive” function, triggering reactions to the information presented.

Once they’ve absorbed the information on the exterior of the pavilion, visitors head up a ramp and move inside the pavilion and into a one-way circulation sequence. Because being inside can be a deeply personal experience, most visitors are polite and let the people before them leave before they enter, even if that means having to wait.

Data related to the four forces of racism is also expressed inside the pavilion, with shorter bars literally forming a void into which visitors can enter. Within this void, visitors can sense the figurative weight of oppression from the metal bars around and above them. They can also get a sense of peace and calmness from being enveloped in a closed-off space, separate from the rest of the Mall. The 15-foot dimension—somewhat greater than a jail cell—is a size that can make the pavilion seem both monumental and intimate.

As soon as they enter the pavilion, visitors are encouraged to hold their breath for as long as they can, so they might begin to understand what George Floyd experienced for 8 minutes and 46 seconds.

After holding their breath, visitors are invited to post a video describing their experience on social media, using the hashtag #SocietysCage. According to the designers, this exercise is meant not only to build empathy on the part of visitors but expand the pavilion’s impact online by allowing people who aren’t on the Mall or even in Washington to see what they post.

The details are brought together in one finite space, the designers say, to make the point that the separate murders of Floyd, Taylor, and others are part of a larger pattern of “unmitigated, unbound, systemic anti-Blackness in the United States.”

The installation provides an opportunity, the designers say, for visitors “to acknowledge and reckon with the severity of the racial biases inherent in the institutional structures of justice,” while also creating a space for collective reflection, sharing, and healing.

Reactions have run the gamut, said Schroeter.

“It can be very soothing for some, and calm and meditative, but very disturbing and eerie for others” he said. “I think that’s sort of the point. Good art allows for that range of interpretation, where people from all walks of life and experiences can really come and see it in their own different ways, through their own lens.”

“We have photos of a mother sort of [telling] her son about it, and her son sort of refused, saying he really didn’t really want to go in the cage,” Arrington said. “We’d had a few people break out in tears. Some people have brought roses.”

This is where the layers of details make an impact.

On the floor of the pavilion are names of more than 10,000 Black Americans who have died over the centuries as a result of racism, the dates of their deaths, and the causes. The victims’ names are coupled with inspirational quotes from artists, poets, musicians, and others related to racism.

“During the day, you see it more as an object. At night, I think you see it more as a space. The light feature is designed to have a sort of constellation effect, like stars,” Schroeter said

Music is part of the experience, too. The designers commissioned a “soundscape” from two composers, Raney Antoine, Jr. and Lovell “U-P” Cooper. It consists of four pieces that together are 8 minutes and 46 seconds long. The musical pieces have themes that correspond to the four institutional forces introduced before: mass incarceration, police terrorism, capital punishment, and racist lynchings.

According to the designers, the cube shape was chosen to suggest that there is a fair and equitable “societal construct.” The void carved out of the cube represents an obstacle-filled path that symbolizes Black Americans’ struggle for survival and America’s imperfect society and justice system.

The bars of the cage represent the “systemic oppression of white supremacy actively subverting Black progress.” One in four bars touches the ground, representing the “statistical probability of being imprisoned as a Black American.”

Facts and figures are provided throughout to make the point that systemic racism creates obstacles in every facet of life, including employment, housing, education, and police violence.

The architects declined to say how much Society’s Cage cost to create. They did note that their employer, SmithGroup, was the lead sponsor. Part of its contribution was allowing staffers to use some company time to work on the project; as a result, “we were our client,” said Schroeter.

The pavilion was fabricated by Gronning Design + Manufacturing LLC in Washington, D.C., and Mejia Ironworks in Hyattsville, Maryland. Besides SmithGroup, corporate sponsors include Advanced Thermal Solutions LLC; Bonstra/Haresign Architects; D Watts Construction LLC; Herrero Builders: Kohler, and the Center for Racial Equity and Justice. In-kind donors include Silman and Alan Karchmer Photography.

SmithGroup has joined with the nonprofit Architects Foundation to raise funds to help pay for the pavilion’s construction and to support the foundation’s Diversity Advancement scholarship program. Donations are still being accepted on the Architects Foundation’s portal.

So far, more than 185 people have contributed more than $64,000, towards a goal of $150,000.

“The tragedies of George Floyd and many others have cemented clearly upon us that centuries of systemic racism and structural inequality cannot be ‘unseen’ anymore,” said foundation president James Walbridge, in a statement. “We are all on a new journey together, with compassion and empathy as our shepherds, to make real societal change. Society’s Cage is a timely partnership for us.”

How did SmithGroup get such a prime spot on the Mall, and did Donald Trump know about it?

The architects said the pavilion wasn’t initially designed with a specific site in mind. They said they originally applied to the city of Washington and thought about being near Black Lives Matter Plaza, a two-block-long section of 16th Street N. W., near the White House.

The mayor’s office referred them to the National Park Service, which offered several options, one of which was the Mall. Schroeter said his team focused on that right away. While putting the pavilion on Blacks Lives Matter Plaza would have been “preaching to the choir,” he said, putting it on the Mall was opening it up to people with a wider range of perspectives, not all friendly to or supportive of the Black Lives Matter movement.

How did the Mall location happen to be available in late August?

According to Christa Montgomery, a SmithGroup corporate communications specialist, the Park Service had just reopened the Mall to the public when the designers applied and had resumed taking permit applications after a period of banning public gatherings to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

“The reason we were able to get a permit so quickly, and for that site, in particular, is actually because of coronavirus,” she said. “We actually got fairly lucky in that they had the site open and available because someone else had canceled. That’s how it worked out. We didn’t have to pull strings or do anything special to get the site. It was just a normal application process. It just kind of worked out well for us. It was serendipitous because other things were canceled.”

The pavilion is now accessible 24 hours a day and never locked. As part of obtaining a permit to build on the Mall, the design team had to agree to have docents there 24 hours a day. Schroeter said volunteers from SmithGroup have signed up to fill all the shifts. He’ll be taking the overnight shift on Wednesday, September 2.

Since August 28, thousands of people have seen the pavilion. After September 12, it will be dismantled and the pieces will be moved to another site, as yet unannounced, for installation and display.

The designers say they hope to see Society’s Cage exhibited in other parts of Washington and in other cities around the country. They about possibly creating more than one of the pavilions to tour the country. They’ve also thought about designing additional 15-foot-cubed pavilions, each with their own materials and music, to explore the life experiences of Asians, Latinos, women, the LGBTQ community, even privileged white men, and possibly putting them all in a row.

“I’d love to see the white male version,” Schroeter said. “I think there would be power in seeing some contrast.”

As for the original pavilion, “We would like to see it live on Schroeter said. “We would hate to junk this thing at the end of its life span. It would be nice if there was an interest in taking this on permanently, as a permanent installation, and so we’re open to that. Who knows? Maybe, in the coming weeks, an opportunity will emerge for something like that to happen. It would be great to keep it where it is, in my opinion.”

Would they like President Trump to see Society’s Cage?

“The idea is that it’s open to anybody to visit,” Arrington said. “We would love to have him, if he comes with an open mind.”