The shift to remote higher learning during the coronavirus era has been messy, improvisatory, and for many students and professors, highly difficult. Yet with this swift pedagogical reshuffling have also come silver linings. The geographic constraints attached to traditional academic venues like lecture halls have been ripped away, and the opportunity to bring new voices—voices that might have been otherwise inaccessible due to pesky practicalities like physical location—into the now-virtual classroom has spurred creative new directions and made the once-limited seem limitless.

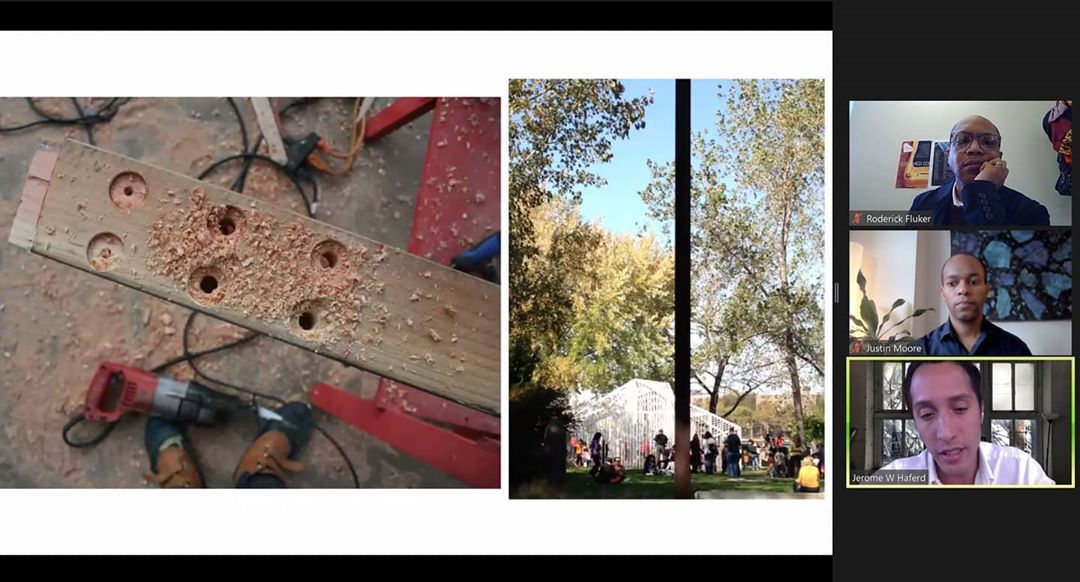

Case in point is the 100-level course (Intro to Careers in Architecture and Construction) offered to first-year undergraduate students at the Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture & Construction Science at Tuskegee University in Alabama, one of a modest handful of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) offering an accredited architecture program and home to the oldest construction baccalaureate program in the United States. While the course is led by associate professor Roderick Fluker, his role has transitioned into more of faculty host as a rotating group of BIPOC design educators take command throughout the semester from far-off locales such as Minneapolis, Cleveland, and New York City.

“They [Tuskegee’s architecture department] happened to have the opportunity to really innovate and experiment,” explained Justin Garrett Moore, an urban designer and executive director of New York City’s Public Design Commission who is one of the five educators presenting content as part of the school’s reimagined intro course. “This happened very fast, and they found the resources to do it in a way that frankly much better situated and privileged institutions have not necessarily made happen.”

Moore, who is also an adjunct associate professor of Architecture at Columbia GSAPP’s urban design and urban planning programs, initiated the dialogue with the school as he was already working on a planned trans-institutional GSAPP/Tuskegee seminar. As Moore explained to AN: “Knowing that we were going to be in this virtual format for some time, I wanted to see if there’d be an opportunity to connect and teach.”

This is where Dark Matter University (DMU) comes in.

Seeking new forms

A wholly collaborative BIPOC-led organization—or “democratic network” as it refers to itself—that began to take shape in the days following the May 25 death of George Floyd at the hands of police officers in Minneapolis, DMU was founded with the mission to “work inside and outside of existing systems to challenge, inform, and reshape our present world to a better future.”

The origins of DMU, per Moore, were “very fluid and truly collective” as two distinct yet interrelated parallel factions—people in architecture and design focused on addressing social injustice issues as part of Colloqate’s Design as Protest (DAP) collective and a more informal network of architects and designers who were already teaching—merged together on a WhatsApp chat to promote ideas, vent frustrations, provide support, and attempt to answer the question: “How can we move built environment design toward justice?” As noted by Moore, these conversations eventually led to formalization efforts and establishing a name for the nascent group: Dark Matter University.

At the core of DMU—a volunteer effort divided into three key working groups: People, Content, and Opportunity—is an urgent push for an anti-racist model of design education and practice achieved by creating new forms of knowledge, community, institutions, practice, and design itself. Roughly 30 BIPOC designers and architects are formally part of DMU while a roster of over 80 design educators and practitioners have, to quote Moore, “endorsed our vision and mission, and committed to education/learning, and practice that align with our work.”

The freshman intro course at Tuskegee is one of just several DMU-affiliated courses planned or underway at several architecture schools across the country. It’s also (save for an upcoming trans-institutional seminar between Yale University and Morgan State University, also led by Moore) the only architecture program at an HBCU that DMU has created content for to date.

Moore recounted the powers-that-be at Tuskegee relaying to him that “we would like for DMU’s network of black, indigenous, people of color designers to help bring new ideas and thought into our curriculum.” Added Moore: “We essentially put a call out to people, and the course was literally created in two weeks.”

Joining Moore (virtually) at Tuskegee for the fall semester are Jennifer Newsom, a Minneapolis-based architect and artist who is one half of creative practice Dream the Combine and also an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota School of Architecture; Jerome Haferd, a cofounder of Harlem-based design practice BRANDT : HAFERD and adjunct assistant professor at Columbia GSAPP; Venesa Alicea, founding principal of NYVARCH ARCHITECTURE and adjunct assistant professor at the Spitzer School of Architecture at the City College of New York as well as president of the college’s architecture alumni group, and Quilian Riano, an architect and urban designer who currently serves as associate director of the Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative at Kent State University’s College of Architecture and Environmental Design.

Prior to the formation of DMU, Haferd noted that the members of the larger network “all kind of knew each other but hadn’t necessarily had meaningful collaboration with each other before.”

“It’s actually a small world,” he added. “In one way or another we were already embedded in academia but now connecting with each other and using our knowledge of the system to create something new and different in collaboration with one another.”

At Tuskegee, each of the five members of the DMU network have crafted single educational sessions reflective of their own individual—and hyper-diverse—professional backgrounds. According to the Moore, the sessions are designed to provide students with “different takes and approaches to the design and construction field, and act as a kind of an anchor to that course.”

“We really wanted to have diverse representation among us—there’s a lot of differences and also a lot of parallels,” remarked Alicea, an architectural licensing guru who comes from a self-described “more traditional background” than her cohorts. In turn, her session drew upon her own professional experiences and strengths.

“I think they’re [the Tuskegee undergrads] are really compelled by the variety, and really widening their understanding of what architecture is, what it can be, and all the different ways you can practice it and ways you can be engaged with it,” added Newsom.

Riano, whose session centered around his own background in civic/social projects that foster community and promote political engagement, noted that the diversity of the group aided in demonstrating to students “the possibilities of multiple ways in which you can practice within architecture without having to compromise your principles and also taking multiple paths.”

“An opportunity to see a path”

While all five educators have already or will lead individual virtual sessions at Tuskegee, during the first class of the semester they all appeared together as a group and each gave, in the words of Alicea, “mini-speed presentations of our careers so that the students had a good sense of who they were going to be talking to” over the course of the semester. After each session, students were invited to fill out online surveys that “help to inform future content” added Alicea.

“When we gave the pecha kuchas on the first day, I think we were really all just so excited to be talking with them,” recalled Newsom. “Reflecting on our own experiences—kind of projecting ourselves onto where they are right now, just starting out—how fortunate we would have felt to be exposed to a wide variety of practitioners who are all doing such interesting things and really carving out their own voices in a discipline that, as we know, has a lot of issues dealing with difference. For them, I think it was it was an opportunity to see a path: here’s somebody who has gone before me, this is what they’ve encountered, this is how they found a way to navigate through, and this is how they are establishing their own voices in this discipline.”

“I think that’s been really the most incredible part of this: seeing that kind of light of realization come over their faces in realizing that they can bring their full subjectivity and full individuality to this pursuit,” added Newsom. (You can watch her session here.)

Haferd also remarked on the potent impact of the inaugural session, noting: “There were so many beautiful and cathartic things about that first session with the students, and it was such a perfect course to be the first one where there’s an array of us doing it in real time together, and demonstrating in real-time this communal paradigm that we’ve come together.”

With most—but not all—of the sessions conceived and presented by Newsom, Alicea, Haferd, Riano, and Moore have now taken place over the previous weeks, another unique component of the DMU-organized course is now underway as a group of young Tuskegee alumni (five in total) are now stepping into the roles of educators for the first time to share their own content and lead conversations with students within this new format.

“We’re maybe more established but part of the way we structured things was to make sure that people that maybe aren’t as well-established also have the opportunity to get into the field and get into education,” said Moore.

Although the end of the COVID-19 pandemic more often than not feels far beyond the horizon, colleges and universities will eventually shift back to more traditional formats. Lecture halls will be filled once again.

But as evidenced by the DMU-affiliated course at Tuskegee University, students—namely BIPOC architecture students considering a profession that’s long been marked by racial disparities—are eager to embrace new models of hybrid learning where real-world representation is more paramount as the curriculum that comes along with it. And where there are eager students, there are also eager design educators looking to impart wisdom.

“DMU and other similar projects out there are showing how we as designers can come together and organize,” said Riano. “And there’s a desire to teach these kinds of processes.”

Dark Matter University is hosting an online fall Open House on October 4 at 4 p.m EST/1 p.m PST. Interested participants can register here.