Santa Monica, California, the affluent oceanfront city bordering Los Angeles, attracts visitors to its beaches and high-end shopping district. A couple minutes’ drive southeast from the latter lies the city’s civic core, which in the past decade has become a hub of a different kind. In 2013, Tongva Park replaced an erstwhile parking lot opposite the Art Deco City Hall, staking out a new model of sustainable public design in the process. Designed by James Corner Field Operations, the park illustrates the variability of experience and aesthetic effects of drought-tolerant ecologies over water-intensive ones (irrigation is supplied by the Santa Monica Urban Runoff Recycling Facility).

As of September, the sustainability mantle has passed onto Santa Monica City Hall East, a contemporary addition to City Hall designed by local firm Frederick Fisher and Partners (FF&P). The building is simple enough, a shimmering extruded box whose silver-blue glazing intermittently offers glimpses into an expansive interior of open-plan offices. Here, however, performance outweighs form: The project, which produces its own water and energy, is expected to achieve Living Building Challenge status, widely taken to be the world’s most comprehensive green building standard. At 50,000 square feet, it would be the largest civic structure to qualify for the certification.

“The building is maybe a little mysterious on the approach,” Joe Coriaty, FF&P Managing Partner, told me as we stood outside the civic complex, “but this allows all the operations taking place inside to be a surprise for the public.”

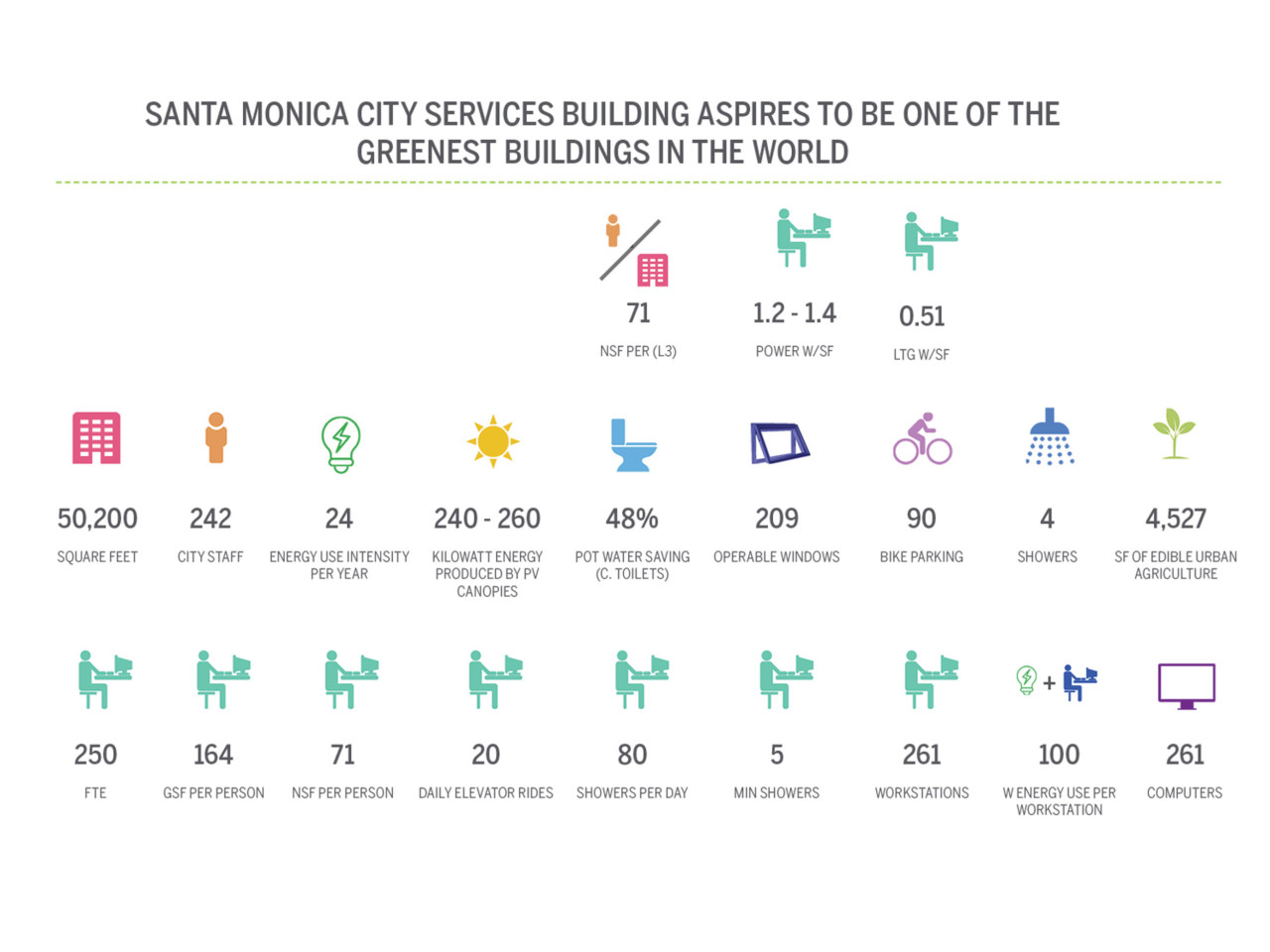

City Hall East, which houses various municipal departments including the Office of Sustainability, Architecture Services, and Finance and Risk Management, boasts composting toilets, on-site farming, water reclamation systems, and an extensive solar array—all shocking for a building of its size and prominence. An interactive display by the front entrance dispenses factoids about the structure’s passive design techniques, while QR codes strewn about the generous courtyard give visitors even more chance to learn about the complex. Exposed mechanicals are everywhere yet neatly arranged, such as on the ground floor, which is for the most part day-lit. (Sensor-activated lighting augments this natural illumination.) The building is outfitted with 209 operable windows designed for cross-ventilation, an effective, nonelectrical way to optimize working conditions throughout the day.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the building reveals its ingenuity only in the basement, where all the systems for recycling and mechanical operations are found. This makes a certain amount of sense; the structure is, after all, the first in California to be granted the right to convert rain-to-potable water on site. City Hall East is effectively off the public utility grid, Amber Richane, Senior Design Manager for the City of Santa Monica, suggested to me on a recent tour. “If the big one ever hit, the occupants of this building could go about business as usual,” Richane said. One look into the composting room, which contains six compost containers the size of station wagons, makes clear that this building performs unlike almost any other in America today.

Engineering firm and Living Building Challenge consultant Buro Happold designed the building systems with a century-long life span in mind, but the architects are hoping that City Hall East’s impact is more immediate. “We hope this building becomes the blueprint for others across the country,” said Coriaty. “Aside from some contextual design measures, it has plenty of lessons that could be adapted to a whole range of climates.”