A Supreme Court decision in April strengthened the hand of organizations striving to broaden access to building codes. In a 5–4 ruling, the court found for the defendant in Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org upholding the right of a not-for-profit watchdog group to post the Official Code of Georgia Annotated online—not only the laws themselves, including building codes, but their nonbinding annotations, created by private contractor Matthew Bender & Co. (a division of research database firm LexisNexis) and adopted by the state legislature’s Code Revision Commission.

The reasoning involved the authors’ role working on behalf of the legislature: Though the annotations are not themselves law, their adoption by the legislature defines them as the product of a public process. They are also essential to practical interpretation of the law, as they include judicial decisions and indicate where certain sections of the text have later been found unconstitutional. As a related case involving UpCodes, a San Francisco firm whose products put searchable codes online and include a Revit add-in, awaits an appellate verdict, the Georgia precedent helps clarify the border between private property and the public domain, with implications for architects using or considering such products as well as advocates of nonmonetized availability of code information.

Standards development organizations (SDOs) such as the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), the International Code Council (ICC), the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), and the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers have long treated both codebooks and annotations as their intellectual property, subject to copyright and paywalls (see “The International Code Council Goes to Court Over Free Access to Building Codes,” AN, July 9, 2019).

Under the Constitution’s copyright clause, Congress protects intellectual property “[t]o promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries,” making copyright a temporary instrumental monopoly rather than an absolute, unlimited right. Wheaton v. Peters, the Supreme Court’s first ruling on copyright, ensured that the court’s own opinions could not be copyrighted by a reporter. The new Georgia decision, citing Wheaton, among other precedents, establishes both the codes and annotations as “government edicts,” in the legal vernacular, outside the scope of copyright.

The ICC, plaintiff in a suit currently before Justice Victor Marrero of New York’s Southern District, International Code Council v. UpCodes, interpreted the Georgia decision as actually favoring its copyright, describing the government-edicts doctrine as “a narrow exception” to copyright protection that does not apply to its international codes (I-Codes), which are used or adopted by 50 states, 12 other nations, and the United Nations. In a statement provided by director of communications Madison Neal, the ICC said, “In our view, the Georgia decision means that courts considering the issue of privately authored model codes ultimately should find that the Code Council’s I-Codes are copyright protected because they are authored by private parties who lack the authority to make or interpret the law.” Georgia’s annotations met the decision’s two-part test (“copyright does not vest in works that are (1) created by judges and legislators (2) in the course of their judicial and legislative duties”); the ICC’s position is that its I-Codes, “regardless of whether they are later adopted into law,” differ qualitatively from Georgia’s annotations and do not meet the two-part edicts test. “Copyright protection and the ability to sell the model codes,” the ICC statement continued, “is integral to ICC’s ability to fund its code development mission.”

The Georgia precedent, say other commentators involved in this and related suits, solidifies the public-domain status of construction standards and supports the position that accessibility is a weightier public priority than material incentives. Carl Malamud, the technologist/author/activist who founded Public Resource in 2007, has posted government documents for decades, including the U.S. patent database, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR), U.S. Court of Appeals back files, and multiple state codes. His group’s victory over the state of Georgia, he noted, is the culmination of a prolonged battle over a principle he finds self-evident: that “the law in the United States belongs to the people.”

“The way I have done things for a long time,” Malamud recalled, “I don’t want to sneak around and put it on BitTorrent and Tor. I bought the Georgia code, I scanned it, I posted it on the internet archive and on my website, and I sent a letter to the attorney general and the Speaker of the House of Georgia with a little peanut thumb drive that had their full code on it and said, ‘You will be pleased to know that the citizens of Georgia now have full access to the Official Code of Georgia Annotated.’ Did the same thing in Mississippi. Got nasty letters back from both… Georgia sued me, and they actually accused me of the practice of terrorism in their district court complaint.”

After back-and-forth verdicts, including a pro-copyright decision at the district level and a pro-public-domain decision in the 11th Circuit Court, the case reached the Supreme Court; Public Resource and its counsel acquiesced to certiorari, reasoning that the issue deserved the highest court’s attention. “Georgia brought in 13 attorney generals with them,” Malamud recalled. “Most of those states are Lexis clients, so there’s no surprises to the lineup there. We had 19 amicus briefs on our side; we had the Cato Institute and the Center for Democracy and Technology, so we had right and left. We had every librarian [and] library association in the country, we had distinguished law professors, we had…the director of the Office of the Federal Register” and others. Amicus briefs on the petitioners’ side represented a comparable range of parties, including the ASTM and other SDOs, Matthew Bender, the National Association of Home Builders, and the Copyright Alliance. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority opinion in a decision that split by age, not ideology: The five youngest justices, including Republican appointees Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, ruled for Public Resource, the four oldest for Georgia.

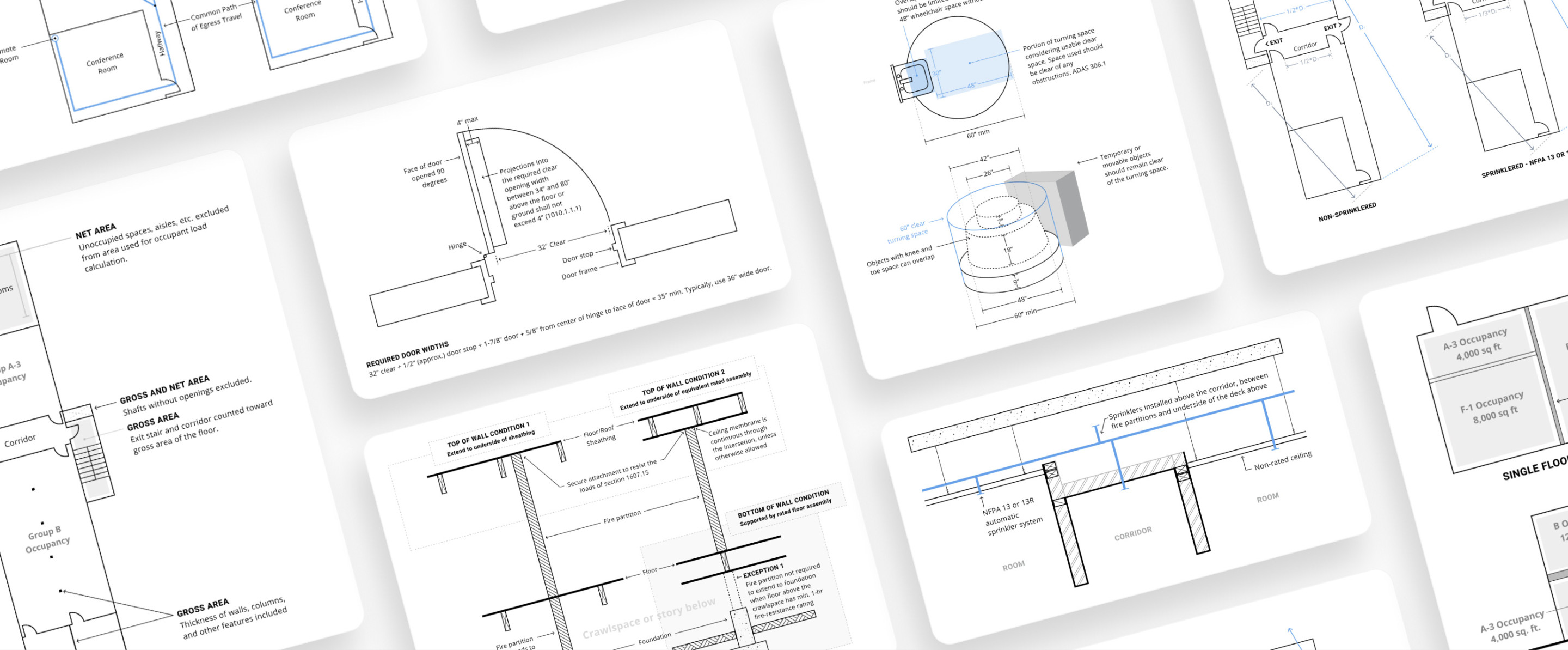

The decision to deny copyright to the annotations surprised some parties who potentially stand to benefit from this precedent. Scott and Garrett Reynolds, cofounders of UpCodes, view Georgia as “actually a much more ambitious case than our own,” Scott Reynolds said. “All we argue is that the law is in the public domain…. It’s really helped our legal fight, but I think where it’ll have the most impact is on other initiatives and innovations in the space.”

Justice Marrero gave open-access proponents a second victory in May, dismissing the ICC’s motion for summary judgment (along with UpCodes’ cross-motion) and sent the case forward for trial, with comments reaffirming that the codes are in the public domain. “The court is not persuaded that ICC’s need for economic incentives can outweigh the due process concerns at issue here, especially knowing that ICC will not stop producing its model code in the event of a contrary holding,” wrote Marrero.

“People aren’t scared of the ICC anymore,” commented Garrett Reynolds, “and I think part of that is because the ICC, or the organizations that became the ICC, have litigated this case before” and lost, particularly in Veeck v. Southern Building Code Congress International, addressing model codes incorporated into law. (The ICC was created in the 1994 merger of three SDOs: the Building Officials and Code Administrators International, the Southern Building Code Congress International, and the International Conference of Building Officials.) “This culture of fear of the ICC in the past has prevented a lot of initiatives [from] getting off the ground that people never even know about,” he continued.

The ICC responded to the Southern District’s dismissal of summary judgment within nine days by suing UpCodes on different grounds: false advertising. Approximately two dozen flaws in UpCodes’ publicly posted codes, the ICC held, invalidated the firm’s claim that its site keeps information up to date and accurate. This assertion may backfire, the Reynoldses contended. “We have now found over 400 sections on their site where they have either an error or they haven’t kept the code up to date,” noted Garrett. In an online repository of court documents and its own commentary on the cases, UpCodes has posted detailed responses to the charges in the second suit.

“When ICC tries to assert themselves as a gatekeeper of the code,” Scott Reynolds said, “they’re attempting to put all the onus on them, so then they would need to create the systems to keep things up to date—and from what we’re seeing on the site, they simply don’t have that ability or haven’t been able to meet that requirement. So the opening up of the laws into the public domain allows companies like our own to come in and specialize in certain areas, like creating tools that can update the codes.”

The ICC’s position that impingement on codebook copyrights will harm its revenue enough to impair the code development process, the Reynoldses added, does not square with its own Internal Revenue Service filings; nonprofits like the ICC, a 501(c)(6) business league, report tax information publicly with IRS Form 990. “You can go see this in their Form 990: Most of their revenues come from program services, not from selling books,” said Garrett. “Consulting, certification, evaluation, things that don’t rely upon limiting access to the law—that’s where they make most of their money.” The ICC’s revenue rose steadily through 2018, the last year for which a 990 is available; UpCodes launched in early 2016. The statement by the ICC describes many forms of code-creation expenses borne by itself and other SDOs (hosting hearings, maintaining IT platforms for public comment, editorial and publication costs), while not indicating proportions dependent on copyrighted material or supported by other sources.

Malamud called attention to a different aspect of the SDOs’ publicly reported finances, finding their executive compensation unusually high for nonprofits. “Pull up the Form 990 for ANSI [American National Standards Institute] and you’ll see not only $2.2 million for the president…. Look at the rest of the executives. You’ll see half a dozen making a half a million a year or hundreds of thousands, in a nonprofit, and it’s a $40 million–a–year operation. They spend 20 percent of their revenue compensating senior managers, which is outrageous.” (Public Resource is a 501[c][3] supported substantially by the U.K.-based Arcadia Fund; Malamud’s own compensation appears on its 990 in the low six-figure range.)

He believes the SDOs’ financial well-being is unthreatened by open access. “If you’re NFPA, you can sell the National Electrical Code, but you’re the official creator of the National Electrical Code; you can sell certification and handbooks and redlines and special training; you have the gold seal of all 50 states of the United States saying the National Electrical Code is the Bible. If you can’t monetize that without putting the damn thing behind a paywall, you’re just not trying real hard.”

“The purpose of copyright is to create incentives for creators,” said senior staff attorney Mitchell Stoltz of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). “When you’re talking about laws, and in particular building codes and so on, that incentive’s not needed. Governments [and] municipalities…have a need for building codes and thus an incentive to see that they are created and updated. And SDOs have an incentive to have their standards adopted as well, because it gives them prestige and the ability to sell some follow-on materials; it gives them influence. And so they don’t need a copyright incentive either.” Standards development is largely performed by uncompensated volunteers from industry and government, he continued, “which suggests that claims about why these organizations need to paywall their standards in order to fund their creation [are] simply not true.”

SDOs continue to defend their copyrights energetically, arguing that they are essential to code development and thus construction integrity. Georgia’s charge of “terrorism” is not the only example of heated rhetoric around these disputes; NFPA president and CEO Jim Pauley, for example, has attacked the public-domain movement for encouraging “people flooding the market with counterfeit versions of our standards, riddled with inaccuracies and peddled for profit without regard to the harm they cause to public safety.” “You’re hearing that in the UpCodes case,” Malamud added, boiling down the ICC’s position to “‘Oh my God, if we let these guys get away with it, this is the end of public safety. Babies will die if you rule in favor of UpCodes.’”

The more realistic outcome, Malamud suggested, is that code access and interpretation will come within reach of more students, members of the general public, and communities burdened by codebook costs. “The County of Sonoma spends $30,000 every code cycle buying the California codes that they have to enforce. It’s a huge budget item,” he said. “So we’re fighting this concept that public safety standards with the force of law must be available. And we’re doing it on a global basis, and we’re hoping to establish that these technical laws are just as important as sedition or income tax or the other laws that are on the books. And in many ways, they are our most important laws. Most people don’t care about sedition; everybody cares whether electricity in their house is safe or not, whether they can build a deck according to code, or whether the building inspector is full of it when the building inspector comes and says, ‘No, you can’t do that.’”

The EFF represents Public Resource in another pending case, American Society for Testing v. Public.Resource.org, which may hinge on questions of fair use under copyright rather than government-edict status. After an appellate hearing in his case, Malamud recalled, he was able to explain his argument in one minute to an Atlanta bartender, whereas the opposing position took about 20; she intuitively grasped it (and comped his drink). “I think that’s significant,” said Stoltz, despite the intricacies of the legal process, “because the simple explanation is the correct one here, and the simple explanation is also the one that courts have mostly reached.” After years of conflict in this area, the fat lady has yet to sing, but she appears to be warming up.

Bill Millard is a contributor to AN, Oculus, Architect, Metals in Construction, LEAF Review, ICON, Content, and other publications.