During a year when exhibitions were postponed, cut short, moved online, or scrapped altogether due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Reviews section of AN still managed to find itself relatively well-populated, all considering. In 2020, critiques of and commentary on in-person art, architecture, and design shows—largely from both the pre- and post-lockdown months—as well as virtual exhibitions were joined, as usual, by a multitude of reviews covering books, films, new buildings, and more.

Below you’ll find six of the most popular reviews AN published in 2020.

The Farnsworth House gets period decor in an effort to shine light on its mysterious owner

Wrote Marianela D’Aprile in her August assessment of Edith Farnsworth Reconsidered, an illuminating exhibition staged at Farnsworth’s eponymous, Mies van der Rohe-designed residence in bucolic (and flood-prone) Plano, Illinois:

“In the commonplace telling of her [Farnsworth’s] story, the one murmured in the hallways of architecture schools after the history lecture is over, Mies appears as a centrifugal force, pulling Edith, objectified, into his orbit. There are stories of an affair, or possible affair, or maybe not an affair at all, but surely she was in love with him—the genius architect, 17 years her senior. How could she not have been?

Edith Farnworth Reconsidered rejects this narrative outright. Countering Edith’s typical objectification, the furniture in the house humanizes her. In one corner of the giant single-room dwelling are her Bruno Mathsson lounge chairs, positioned how she would’ve had them, with a book on the small table in between, and binoculars for bird-watching. In another, there is her desk, with a typewriter and a book of Italian poetry that she translated once she’d retired from her practice as a researcher and physician. A violin attests to her training in classical music. There are flowers and plants scattered about, silverware on the dining table, a bottle of vermouth on the kitchen counter. These items constitute Edith’s presence.”

Spaceship Earth is a tale of quarantine set within a massive geodesic backdrop

Wrote Fred Scharmen of Biosphere 2, the Arizona research facility that serves as the backdrop for Spaceship Earth, filmmaker Matt Wolf’s feature-length documentary that chronicles a two-year-long experiment that kicked off in 1991—a cause célèbre at the time—and involved eight researchers quarantining inside of a self-contained replica of Earth’s ecosystems for a two-year span:

“The structure of Biosphere 2 was designed by Peter Jon Pearce, a former assistant of [Buckminster] Fuller’s, and its triangulated geometry owes much to the latter’s famous domes and to large-span space-frame systems originally developed by Alexander Graham Bell. Inside these latticed vaults, roofs, and domes, Biosphere 2’s ecologists placed several ‘biomes’: a desert, a grassland, a tropical jungle, a mangrove swamp, even a small ocean, complete with a coral reef. This was the set of ‘wilderness’ places, but there were other more cultivated human spaces as well, including dwellings, labs, farms, and extensive technological underground infrastructure. During the two-year initial mission, nothing was to enter or leave the Biosphere except energy, sunlight, and information, the latter transmitted by video and audio uplinks.

This may sound like the perfect place for self-isolation, especially during the stay-at-home orders of the past several weeks—but not much ran smoothly during this quarantine. What started as a set of utopian experiments intended to improve life on Earth and in space ended up coming apart at the airtight seams. Spaceship Earth shows how the story of Biosphere 2 is ultimately not about the past or the future, but the present.”

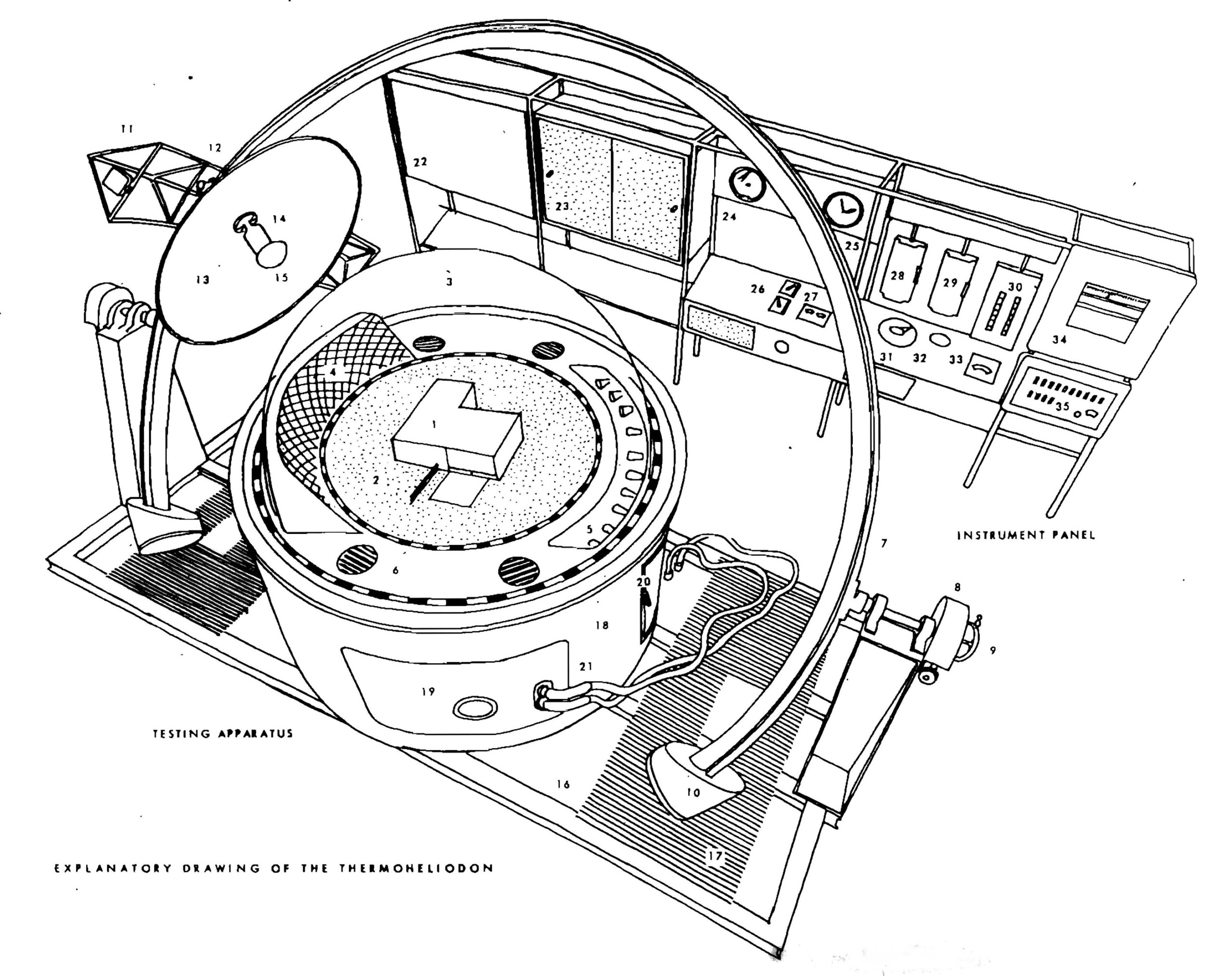

In Modern Architecture and Climate, climate control takes command

Wrote Kate Wagner in her July review of Daniel Barber’s Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning from the Princeton University Press:

“Underlying Modern Architecture and Climate is a distinct tension. On the one hand, these architectural solutions to climate control, born from interwar and postwar moments when the belief in the power of architectural design to change lives was at its height, offer us alternative solutions and histories to the carbon-intensive, air-conditioned era that was to follow. In the brises-soleils, louver shades, microclimate diagrams, and adaptive climate design methodologies that proliferate in Barber’s monograph, we can find inspiration in a contested past that lends historical credence to contemporary practices even as it offers a glimmer of a radically different future. The latter was clearly a missed opportunity, whose success in the fight for architectural hegemony would have profoundly changed the world and modes of inhabitation in ways dizzying and despair-inducing to comprehend.

Meanwhile, by the time my modernist apartment building was built in 1966, the prospect of an architectural solution to climate control was fading fast, kept alive only by white lab coat researchers and hippie modernists, neither of whom were given a second thought by my building’s developer. So quick was the transition between climate modernism and the Great Acceleration that the former has become the subject of specialty books printed by architectural presses while the latter has become a reality of everyday life and an uncertain future. The architecture’s form and architects’ desire to be form makers above all else soon reified climatically horrible buildings like the Seagram Building to the status of legendary innovations and cheerily handed over the reins of climate control to HVAC engineers so that the pursuit of form could be continued unabated during the postmodern turn.”

Flight Simulator 2020 provides a worldwide playset for architects and urbanists

Kevin Rogan covered Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020, a flight simulator developed by Asobo Studio and published by Xbox Game Studios with Austrian AI startup Blackshark.ai playing a key role:

“…Before any of Blackshark’s worldbuilding can begin, the existing data must be stripped down and decontextualized. Information about buildings is categorized by typology and regional differences—that is, not as high-fidelity spatial artifacts on their own, but as mix-and-match parts that can be understood by the system. Typically, Blackshark’s algorithm may detect a building footprint, estimate its height based on the shadow, and then apply facade details, roof furniture, and so on—with the final product not necessarily corresponding to what exists but constituting a generic version of what likely would exist. Blackshark CEO Michael Putz admits that the actual process of this algorithmic “construction” is an arcane “black box,” unknowable and vague. This black box occasionally suffers from memorable hiccups that escape quality checks, such as the Washington Monument appearing as a pseudo–Seagram Building, the sudden existence of a slender monolith in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia, and an abyssal pit in Brazil.

This process is less akin to a cartographer meticulously preparing a map than an automated factory churning out commodities. A slew of data and raw material inputs (point cloud data, satellite photos, etc.) go in, technological wizardry is applied, and finished objects (fake buildings to populate a virtual planet) emerge on the other side. The sheer scope of Blackshark’s project makes this inevitable; having human workers determine and build structures and their design elements directly is too costly and time-consuming. Flight Simulator 2020 is not about accuracy; it’s about instilling awe at the ability to approximate the planet in its entirety quickly and, thanks to the infallible logic that is often imputed to AI, mostly without complaint.”

Does the Hollywood Hard Rock Hotel rock, or is it a one-hit-wonder?

As Alice Bucknell reflected following her visit to the 450-foot tall, guitar-shaped expansion of the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Hollywood, Florida:

“While it’s fair play to criticize the very existence of a guitar-shaped luxury hotel as our relationship with the Earth grows more precarious, or find fault with the detrimental social impact of gambling, which preys on minorities and unemployed, you can walk away from a weekend at the Guitar Hotel knowing the livelihood of the Seminoles grows stronger for it. In addition to a $1,000 check paid out monthly in their name along with free college tuition, every tribe member currently receives dividends of their gambling empire paid out to around $128,000 a year. In other words, every Seminole member reaches adulthood with over $2 million in reserves. Rarely do ethnic minorities make it so big in the US — a country that built its wealth on the forced displacement, persecution and eradication of indigenous groups. At the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel, the right guys are on the winning end of your bad poker face.”

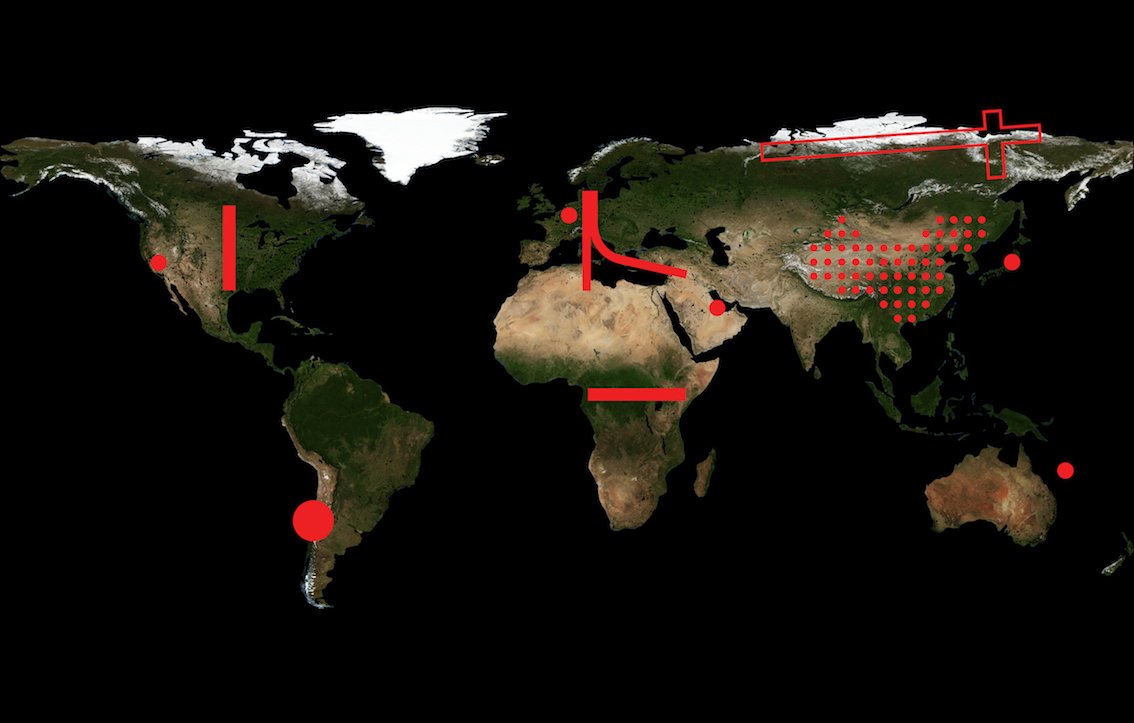

Rem Koolhaas sets a global non-urban agenda with Countryside at the Guggenheim

Former AN executive editor Matt Shaw had plenty to say in his February review of Rem Koolhaas’s much talked-about Countryside: The Future show at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York:

“Countryside is definitely a magazine- or book-on-the-wall type of exhibition, but not in a bad way. The texts are snappily written in typical Koolhaasian style, and there are not too many complex maps or charts, making the exhibition feel more like a journalistic analysis of what is interesting about the countryside, not necessarily a theoretical treatise or prescriptive path forward. It could be read as a transformation of the museum into a publication, a curatorial strategy that upturns not only our ideas about the Guggenheim but about how to leverage a hyper-didactic exhibition into an aesthetic experience. The show is literally distorted by the Guggenheim’s double-curved surfaces, spiraling ramp, and constantly shifting vantage points, with a string of text spiraling around the underside of the ramps like a dizzying thesis statement, always to be revisited.”