Our cities contain a diverse population and a multiplicity of family types, but our cities’ spaces don’t accommodate everyone. How we design spaces for a city’s broad range of family types is an unspoken urban challenge, but one of significant impact. The events of the past year have made this disconnect more apparent; as a society, we must reframe our thinking to design spaces that suit the needs of a more inclusive range of our community’s families.

Back in late spring, at the height of the pandemic in New York City, a daily walk was one of the few respites available to many for fresh air, exercise, and for an opportunity to experience a connection with others beyond one’s immediate household. In that early phase of social distancing, streets were full of small groups of people huddled together in their six-foot bubbles, grouped by household and casting wary glances at others as they passed by or were perceived as too close. These groups came in all shapes and sizes—a mother and her adult children; a grandmother, uncle, and a large cluster of cousins; a grandfather, his friend, and their children. In a city famed for its anonymity, the physical distancing affected by the pandemic put on display the living situations of others, offering a rare glimpse into our city’s de facto definition of family and household.

The heightened visibility of the household makeup of our city’s residents has highlighted the inequities in access to safe and affordable housing and the disparity of living conditions in dense urban environments. It has been well documented that minority and low-income communities are disproportionately affected by the pandemic on a multitude of levels. Digging deeper into their circumstances, these affected households are often composed of large families crowded into apartments intended for smaller households.

Today, shared households may include both intergenerational and extended family as well as non-related adults driven to inclusion by both financial considerations and cultural values. When adequate space is provided to meet their daily needs, these households can reap social, economic, and educational benefits. Overcrowding emerges out of a misalignment between dwelling unit capacity and household size. As I recently stocked up on weekly groceries, I passed by a large carton of snacks labeled Family-Size. Family-size is defined as “large enough to suit or satisfy a whole family.” What features of affordable housing design must change to be “family-size” and suit the needs of the families who live there? And how can reconsidering the definition of family influence a more equitable approach toward housing design?

A look back at the history of affordable housing in our country reveals an underlying bias that has privileged certain family structures and idealized versions of family life. The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), founded in 1934, was the first agency to provide publicly funded housing in the United States. While the organization and the challenges it faces have evolved considerably, in its infancy its services were in high demand, and a lengthy list of potential residents, screened both on merit and need, sought admittance to its various developments. Priority was often given to applicants with secure incomes and nuclear family structures, as opposed to single parents, those with less stable employment histories, or individuals with prior mental health or substance abuse challenges.

Assumptions of what constitutes a family unit has also posed barriers to housing opportunities for “grand families,” where grandparents raising grandchildren may not meet family eligibility requirements without formal guardianship or encounter the challenges of age-restricted communities. The predisposition toward design for smaller families extends to the privately developed subsidized housing markets, where program guidelines incentivize studio, one-, and two-bedroom apartments over larger unit types and shape the available housing stock in a specific direction. Federal legislation requiring fair access to housing broadened need-based opportunity, but barriers to adequate options for extended households and intergenerational living remain.

The design process for laying out apartment floorplates designed under current housing agency guidelines is a complex calculus of maximizing efficiency, balancing the number of units, room dimensions, and square footage, and calibrating everything from kitchen appliance size to closet length. In cities where land and building area are limited and housing needs are great, policy metrics often focus on quantitative data, rather than a more nuanced set of standards that could provide flexibility for family diversity and better suit the living situations of the intended community of residents.

In considering steps toward a more family-size and family-inclusive housing policy, useful parallels exist in emerging housing typologies that have aimed at limiting the rent burden among a diverse range of communities. Co-living of non-related adults and emerging professionals has strengthened in popularity over the past decade. This typology has assumed several forms—from buildings comprising micro-units with robust community and amenity spaces, to apartments with multiple suites of bedrooms and bathrooms and shared in-unit common space. In New York City, the Department of Housing and Preservation recently launched a pilot program that leverages developers, not-for-profits, and co-living operators to explore similar approaches in the affordable housing sector, while other cities have been experimenting with loosening restrictions on accessory dwelling units and mixed-use developments that blend age groups and typologies. Minneapolis instituted zoning changes that legalized Accessory Dwelling Units, often referred to as a “granny flat,” in 2014. And Washington, D.C., has developed a subsidized housing community tailored to the unique needs of grandparents raising grandchildren.

At FXCollaborative, our practice has been exploring pandemic-responsive design and considering how the events of the last year should inform our design thinking moving forward. What began as a study in pandemic resiliency quickly evolved into a more comprehensive discussion of design equity: of questioning our assumptions, of deliberate efforts to inquire and understand, and of considering how to co-create with, rather than design for, a community. Healthy and affordable housing is critical in establishing a foundation to achieve social, financial, and health equity, and must be accessible to both individuals and families alike.

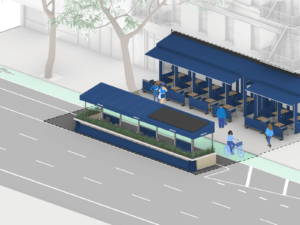

In considering how apartment design can adapt to reduce overcrowding and right-size to accommodate larger households, we are exploring alternate floorplate depths and distributions, studying scenarios in which an apartment has multiple primary bedroom suites, and relocating spaces within a unit to increase privacy and provide study and workspaces in multiple rooms. We are considering how units can adapt to multiple configurations to create privacy and distance and simultaneously provide opportunities for gathering. And we are reevaluating amenity and outdoor spaces and how they can serve to create community and extend living space for larger families.

In parallel with investigating potential design opportunities, we are also analyzing current design parameters and identifying existing challenges—agency standards that set limits on maximum unit and room sizes, prescribed unit layouts that limit flexibility, and zoning requirements that restrict residential density and limit outdoor space.

But solutions to reducing overcrowding and increasing choice for family housing options is not simply a design problem and exists at the intersection of design, economics, and policy. As affordable housing development is reconsidered more generally, it is important to define broader metrics of success to ensure that the nuances of family, household, and health are understood and prioritized alongside other important empirical criteria. Apartment size and physical space is one component, with funding, access, and income eligibility determinants being others. We—as a collective of architects, stakeholders, and policymakers—must take the time and invest the resources to understand how families are living, empathize with their needs, and actively engage them to inform the reshaping of policy and creation of spaces that safely accommodate a diversity of living experiences.

The pandemic has exposed barriers families face in access to affordable, suitable, and healthy housing. We must take this as an opportunity to reset, reflect, and reframe past assumptions of family life and use this as a catalyst to design for a more equitable future.