New York’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) put the brakes on a $70 million renovation project at the Metropolitan Museum of Art after the head of Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates expressed concerns about the proposal to change part of the museum his firm had designed four decades before.

Eamon Roche, managing director of Roche Dinkeloo and son of the late architect Kevin Roche, was the most vocal of several speakers who raised questions during a public presentation by Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners, showing how it proposed to replace the south-facing glass wall of the museum’s Michael C. Rockefeller Wing.

Roche politely but firmly told the commissioners that Beyer Blinder Belle’s design represented a departure in several key respects from the approach that Roche Dinkeloo took when it designed the Rockefeller Wing and that he believes it should be reconsidered.

“We respectfully find the aesthetics resulting from the proposal to be a bit of a loss,” Roche said during the panel’s February 9 virtual meeting. “There are three principal design elements at play in this proposal and we feel that at least two of them could be handled differently to ensure the architectural result is both better and more historically in keeping with the original design.”

Roche started his testimony by thanking Beyer Blinder Belle for making a “great presentation” to the commission. But he went on to say he thought its proposal was “underwhelming,” “less appealing” than his firm’s design, and would be a “detriment” to the relationship between the museum and Central Park.

Michael Wetstone, a principal for Beyer Blinder Belle, acknowledged that the design he showed was different from Roche Dinkeloo’s existing curtain wall but said his team had good reasons for recommending what it did.

After a lengthy discussion, commission chair Sarah Carroll said the panel would take no action until it could get more information to help members make a decision.

Absent from the discussion were two commissioners who recused themselves because of conflicts of interest, vice chair Frederick Bland, the managing partner of Beyer Blinder Belle, and Wellington Chen, a museum trustee.

The issue that raised concerns for the commission came down to a matter of weighing consideration for aesthetics and the original architect’s design intent against a desire to improve the technical performance of the museum’s infrastructure in conserving energy and protecting the art and artifacts inside the Rockefeller Wing.

Constructed in 1982, the 40,000-square-foot wing houses fine art from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. Brett Gaillard, head of capital and infrastructure planning for The Met and a former senior associate at Beyer Blinder Belle, told the commission that the project would be the first substantial renovation and reinstallation of the Rockefeller Wing since it opened. In addition to Beyer Blinder Belle, the Met has selected wHY Architecture, led by Thai architect Kulapat Yantrasast, to serve as the exhibition designer.

Roche Dinkeloo, successor firm to Eero Saarinen and Associates, was first hired by The Met in 1967. For the next four decades, it was the architect for the museum’s master plan and its expansion, designing all of its new wings and installing many of its collections.

Dinkeloo died in 1981 at age 63 and Kevin Roche died in 2019 at 96. The firm has continued under the leadership of Eamon Roche and is now based in downtown New Haven, after years working from a mansion in Hamden, Connecticut.

In recent years, the Met has hired different architects for various projects, including Roman and Williams Buildings and Interiors to lead a $22 million renovation of its British Galleries, and British architect David Chipperfield to develop a new design for its southwest wing for modern and contemporary art, a project that hasn’t made much progress as of late.

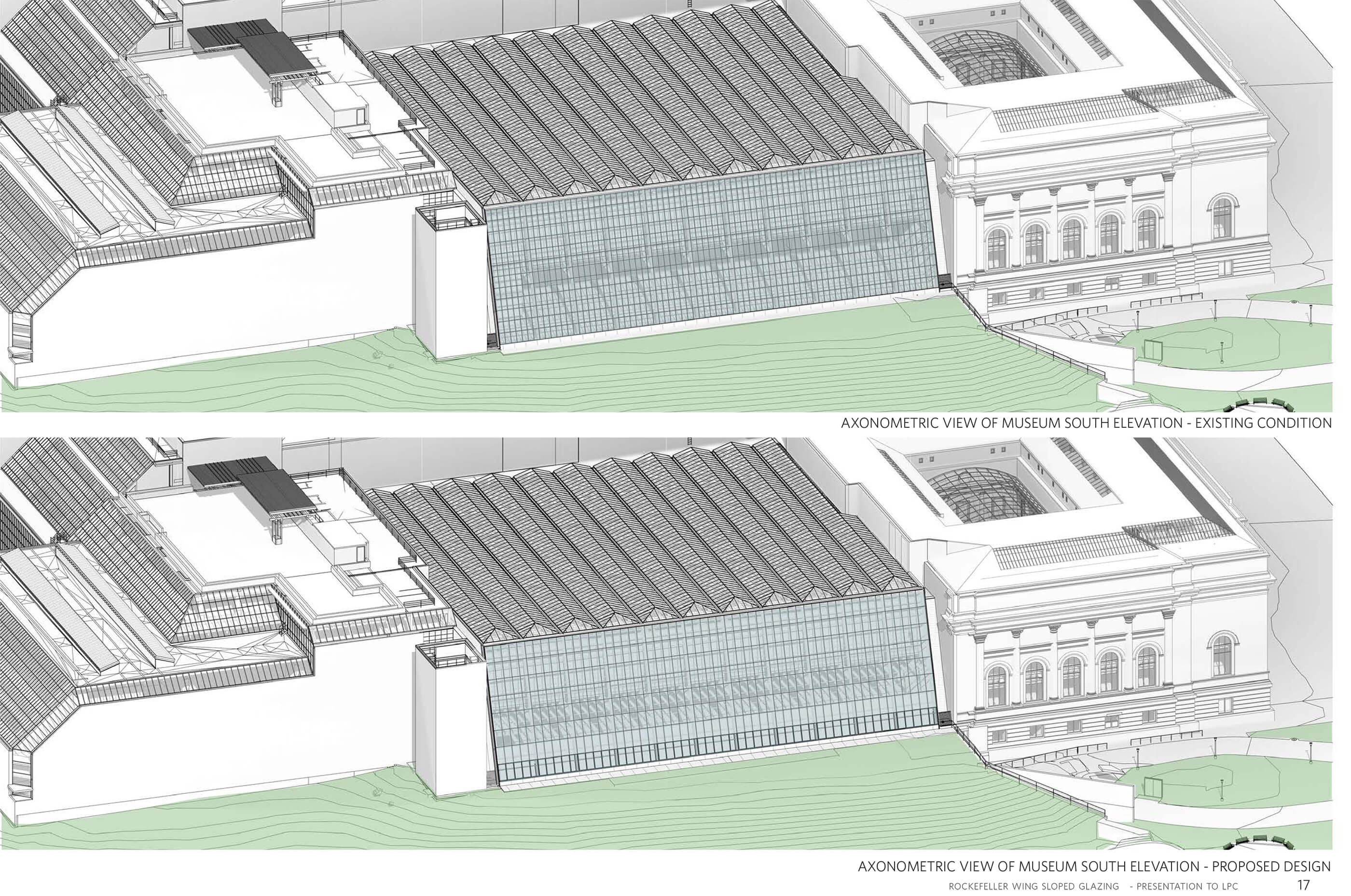

The sole subject of the commission’s February 9 meeting with The Met was the design of the Rockefeller Wing’s curtain wall, which will be 200 feet long and 60 feet tall.

The commissioners didn’t look closely at wHY’s plans for the exhibits thenmselves but they did discuss how the proposed wall would affect the visitor experience and the museum’s ability to protect art on display. The commission has the authority to review and approve changes because The Met has city landmark designation.

Gaillard said the museum’s goals for the project are both curatorial and infrastructure related.

“The care of the collection is as important as how we display it,” she said. “We want to conserve these objects with the same level of care [as] its neighbors in the Greek and Roman galleries or our European paintings collection, and so it’s critical for us to be able to replace the aging infrastructure to meet the demands of a 21st century museum environment. This includes a full replacement of the sloped glazing on the south facade to control condensation, improve energy efficiency, control daylight for light-sensitive objects on the inside and also to protect birds in the park.”

Wetstone said the design team is following the original Roche Dinkeloo concept of placing a sloping glass wall between two limestone masses. He said the replacement wall will slope at a 20-degree angle, just like the current wall.

In replacing both the glass panels and the framing system that holds them in place, he said, the design team wanted to address problems that the museum has had with the wall since the wing opened, including direct sunlight that has prompted the museum to install window shades, excessive solar heat gain in the summer and condensation dripping from the glass in the winter.

Since the building opened, he said, the museum has adopted climate control standards that call for indoor temperatures to remain at 70 degrees Fahrenheit and relative humidity of 50 percent year-round, but the Rockefeller Wing hasn’t been able to meet those levels.

Unlike the Sackler Wing’s exterior wall on the north side of the museum, he said, “this wall faces south, and you can immediately begin to understand the problem of displaying artwork behind an enormous glass wall just in terms of solar heat gain and the rays of the sun providing too much sun.”

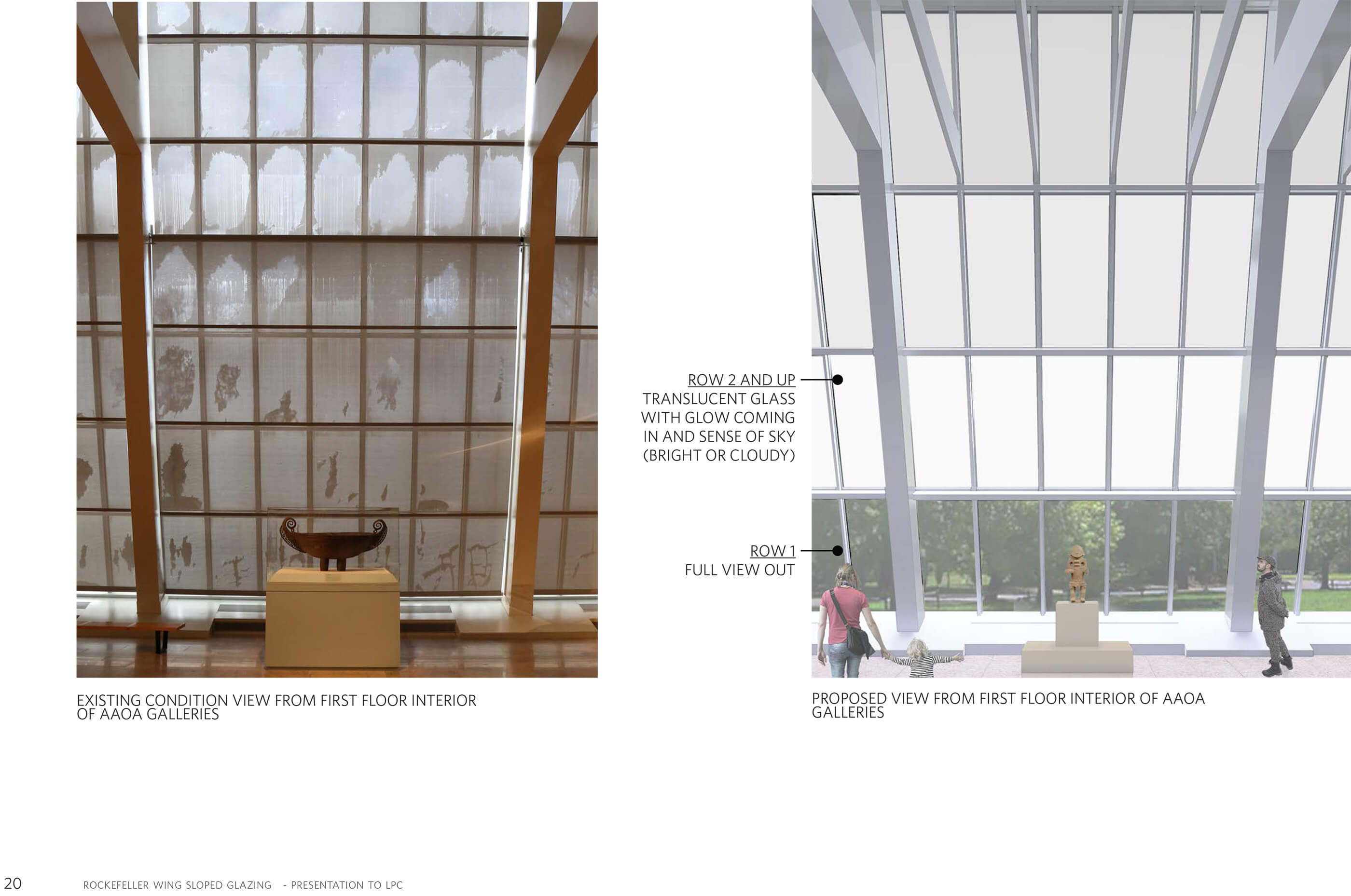

Wetstone said Roche and Dinkeloo understood the challenges of a south-facing wall and specified two kinds of glass to control the amount of natural light coming in: A transparent layer at the bottom and more translucent glass above.

Despite their foresight, he added, the curtain wall and glass technology of the 1980s “was perhaps not quite up to the role of handling the situation, and there’ve been a lot of remediative efforts taken since.”

Wetstone showed the commissioners a 1982 photo of window shades that the museum installed to prevent sunlight from beating into the galleries.

“These shades have been in place full-height, permanently, since the day the building opened,” he said, “because the sun and the heat was just too much for the more delicate wood and textile objects housed within.”

Though state-of-the-art 40 years ago, it “was never quite able to withstand and protect the museum environment from the outside, particularly with the humidity and temperature levels that were required,” he said. “There’s been a chronic problem of condensation and water dripping onto the floor and on the artwork.”

To address the museum’s problems, Wetstone’s team recommended changing both the size of the laminated glass panels and the composition and dimensions of the structural system holding them up.

Regarding the size of the glass panels, he said, his team recommended increasing the dimensions from 2’6” wide and 5’ tall, to 3’7” wide and 7’6” tall.

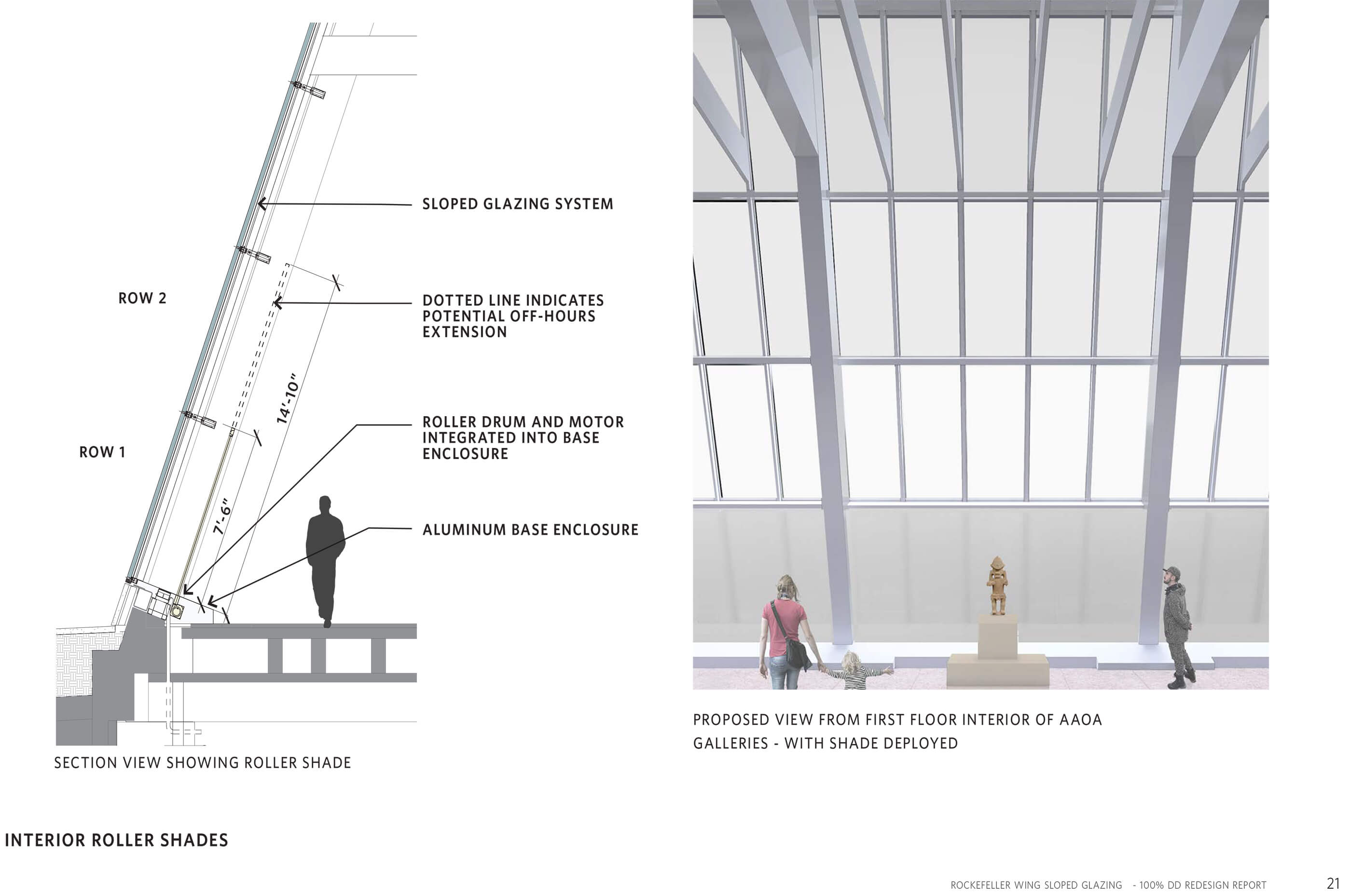

The team recommended still having one row of transparent “vision glass” at the bottom of the wall and more translucent glass above it. It also recommended a frit pattern on the surface to keep birds from flying into the wall—a new requirement of the New York City building code starting this year.

In addition to changing the size of the glass panels, he said, the team recommends changing the framing system that holds the glass in place from a captured glazing system to a structural glazing system. While this recommendation is driven by a desire to improve the wall’s technological performance, it also has aesthetic implications.

The Roche Dinkeloo design, he said, was a relatively conventional system with raised aluminum caps over the mullions that form a noticeable grid on the wall surface.

Part of the problem the museum has had from a thermal standpoint, he said, is that the caps over the mullions are attached by “thousands and thousands of little metal screws and connections between the glass” and they don’t provide an airtight seal. As a result, “this curtain wall was just inadequate” in helping the museum maintain the consistent temperature and humidity levels the directors wanted, he said.

Working with the facade experts at Arup, Wetstone said, his team has recommended switching to a structural glazing system that wouldn’t have caps on the outside to secure the glass.

The proposals to change the size of the glass panels and eliminate the raised caps drew the most questioning from Roche and others who offered public testimony.

Roche said his father determined the proportions of the glass panels and the dimensions and detailing of the frame after carefully considering the way the facade would be perceived from both inside and outside the museum.

“In terms of the size of the glass units, we find that the proposed larger grid is less appealing in its scale,” he said. “The scale of the existing grid was originally arrived at not just for its interplay with the exterior elements but, just as importantly, for the experience of the museum visitor. The gridded glass in that sense is both a series of windows and elegantly and insistently a kind of beautiful boundary. The idea, well-realized in our opinion, was to find a perfect delineation between inside and outside.”

Roche also took issue with the proposal to eliminate the raised caps, which he said give the wall shadows and texture that a flatter surface wouldn’t.

“The pronounced gridding and texture created by the existing captured system with the exterior pressure caps is much more than just a way to hold the glazing units in place,” he said. “The lattice created by the caps defines a very considered scale and sets the planes of the glazing in a precisely calibrated contrast to the almost featureless monoliths of limestone that bookend it.”

By contrast, said Roche, “the gridding potential of the proposed structurally glazed curtain wall is really limited on the exterior to the visual impact of the sealant joint, and I think that the result appears underwhelming in that regard. Therefore, we would suggest that the captured glazing continue to be considered as part of the new scheme.”

To drive home his point, Roche read an excerpt from a 1974 critique of his firm’s master plan for The Met by architecture critic Paul Goldberger. Writing for Architectural Forum in one of its last issues, Goldberger compared the glass-clad wings that Roche and Dinkeloo designed for The Met to the Crystal Palace, a glass and cast iron exhibition hall that Sir Joseph Paxton, a botanist and greenhouse builder, designed for the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London.

Paxton’s Crystal Palace marked the introduction of a new method of “sheet glass” construction in Britain, involving large sheets of inexpensive but strong glass set in a metal frame made with thousands of prefabricated parts.

When it opened, the Palace boasted the greatest area of glass seen in one structure up to that point. The juxtaposition of glass with cast iron gave the building a sense of texture and scale that glass alone wouldn’t have had. Sir Norman Foster has said the Crystal Palace represented “the birth of modern architecture.”

Roche said he’s concerned that any reference to greenhouses or conservatories will be lost if the museum adopts a wall design that eliminates the raised caps and downplays the frame.

“We find that the current proposal will scrub this historical allusion to the detriment of the museum-park relationship it serves so well,” he said.

Roche also said he wouldn’t want to see any design change to the glass wall that encloses the museum’s Sackler/Temple of Dendur Wing, which is identical to the Rockefeller wall except that it faces north and doesn’t get direct sunlight.

“We are confident that the future Temple of Dendur curtain wall renovations can maintain the existing threefold scheme of captured glass fully transparent and unitized at the present scale, given that this wing is both north-facing and endowed with artifacts that are largely impervious to UV degradation,” he said.

John Arbuckle, president of the New York/Tri-State chapter of Docomomo U.S., said he shares Roche’s concerns and is worried that the wall proposed by Beyer Blinder Belle would read “much more as one single flat plane of uninterrupted glass.”

The exterior caps of the original system “protrude from the surface of the glass, adding depth, casting shadows and clearly articulating the individual glazing units,” Arbuckle said. “While we understand that the proposed system utilizing structural glazing is technologically superior, we regret that its exterior appearance would be so different from that of the present system.”

Wetstone said the grid dimensions and glass sizes were changed in part because the curators asked for it. He said the five-foot-tall height of the glass panels means that the horizontal line above the first row of glass tends to block some people’s views out to the park. He said curators wanted to have the first row of windows “higher than head height” so people could see out and have a “less cluttered experience.”

Laminated glass is also more efficient than the framing system in terms of providing a thermal barrier, so if there’s more glass and less framing the museum will have more ability to control temperatures and limit condensation.

Wetstone said he wasn’t sure how many people would even notice the elimination of the caps or the change in the grid dimensions. He said most people don’t ever stand next to the wall because the building is on a hill and the nearest pedestrian path is 50-to-75 feet away.

He also threw cold water on the idea of retaining pronounced caps, saying they don’t satisfy the museum’s climate control needs the way the silicone seal does. He said there could be ornamental caps over a silicone seal, but that would add to the project’s cost.

At the end of his presentation, to show that his team’s design is consistent with Roche and Dinkeloo’s vision, Wetstone pointed to an image of a scale model that depicted an early vision for the Rockefeller wing and its sloping wall.

“In this 1970 master plan model you can see that they don’t actually show the individual curtain wall grid,” he said. “They just show this abstract single slope of glass, kind of a very expansive and optimistic and progressive vision of the future of The Met… So I would just like to suggest in closing that this original architect’s conception of the sloped glass wall is very much in keeping with what we are currently proposing.”

Several of the commissioners picked up on Roche’s comments, saying they understand the need for the museum to protect its collections and operate efficiently, but they also want to respect its architecture and Roche’s design intent.

Some said they wanted more information about how much the Crystal Palace or other park buildings may have been a design inspiration for Kevin Roche.

“I think there’s something to be said for the arguments that have been made in the [public] testimony about the need for more texture” on the wall, said commissioner Michael Blumberg.

“Once you change the grid, you change the aesthetics. We all know that,” added Everardo Jefferson.

“I think it all goes back to original intent, which I think we don’t necessarily know yet,” said commissioner Anne Holford-Smith. “If this was to be really treated as a greenhouse at a fine scale, then changing the scale of the glass and eliminating the mullions is something that we should not be doing.”

The key, Sarah Carroll said, will be finding a way to address both the aesthetic considerations pertaining to the architecture and the technological considerations of protecting the collection and serving the visitors.

“There’s the question of the original intent,” she said. “There’s the aesthetic or design question. And then there are the technical requirements for inside temperature and humidity control, which I think is as important a factor for us to consider given that the museum is a landmark as a museum and understanding that the collections are part of the continuation of their mission as a museum. “

While each of the proposed changes by itself may seem subtle, she said, “maybe it’s the combination of them that is giving people some pause. The change in the size of the panel, the silicone versus something that would have a profile…I think a little more information and research on some of these aspects would help inform the discussion and help us move toward an action.”

“Beyer Blinder Belle is a very fine firm,” said Roche. “We hope that they along with the commission and the museum will take our suggestions as our sincere desire to see the best possible outcome for these renovations.”